AP Syllabus focus:

‘Geographic data can be collected in the field by individuals or by organizations, producing observations and measurements.’

Field data collection underpins geographic inquiry by generating firsthand observations and measurements that help geographers understand spatial patterns, human activity, and environmental conditions across diverse landscapes with accuracy and context-rich detail.

Understanding Field Data Collection

Field data collection refers to the systematic gathering of geographic data directly from real-world locations rather than from remote or secondary sources.

Students collect field data in a forest using measuring tapes and clipboards to record observations and measurements. This mirrors common geographic fieldwork methods used to quantify environmental or cultural features at specific locations. The scene includes extra ecological detail beyond the AP syllabus, but it still exemplifies core field data collection practices. Source.

It provides raw, location-specific information essential for analyzing spatial relationships, validating models, and producing high-quality geographic representations.

What Field Data Includes

Field data encompasses a wide range of measurements and observations, which may be qualitative, quantitative, or a combination of the two. Geographers select methods that match the research question, location type, and level of detail needed.

Quantitative data: Numerical information such as temperature, population counts, building heights, traffic volume, or soil moisture levels.

Qualitative data: Descriptive information such as perceptions of place, observed behaviors, cultural characteristics, or landscape features.

Key Terminology in Fieldwork

Field Observation: Systematic noting and recording of geographic phenomena as they appear in the real world.

Field observation allows geographers to capture spatial patterns in ways that remote or synthesized data often cannot replicate.

Purposes of Field Data Collection

Field data collection provides essential evidence for geographic analysis, allowing geographers to:

Document physical characteristics such as vegetation, landforms, and climate conditions.

Record human activities, including land use, settlement patterns, and transportation flows.

Verify or correct information obtained from maps, GIS, or remote sensing.

Develop deeper insights by experiencing place-based cultural and environmental contexts.

Produce original datasets for research in urban planning, environmental management, and cultural geography.

Major Methods of Collecting Field Data

Direct Measurement

Direct measurement involves using instruments to record precise environmental or spatial variables.

Thermometers, anemometers, and rain gauges for climate measurements

GPS receivers for exact coordinate recording

Rangefinders or measuring tapes for distances and dimensions

Soil probes or pH meters for environmental sampling

Direct measurement is valued for its precision, enabling geographers to quantify spatial variation with replicable results.

Surveys and Interviews

Surveys gather information from individuals or groups to understand human behavior, opinions, or demographic characteristics.

Survey: A structured set of questions designed to collect data from respondents about behaviors, attitudes, or characteristics.

Surveys help geographers study phenomena such as migration motivations, land-use decisions, or perceptions of neighborhood identity.

Interviews—structured, semi-structured, or unstructured—provide richer qualitative insights that deepen understanding of local contexts.

Field Sketching and Mapping

Field sketches capture the layout of landscapes and the spatial relationships between features.

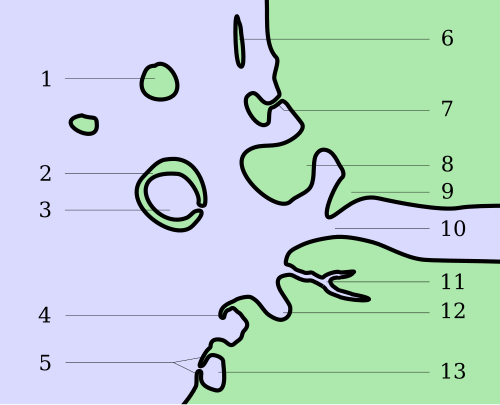

A simplified coastal field sketch highlights key landforms and labels them directly on the drawing. This kind of annotated sketch helps geographers record what they observe in the field and later relate it to maps or other data. Some of the specific coastal landforms labeled here go beyond AP Human Geography requirements, but the overall technique strongly reflects how field sketches support geographic observation. Source.

Geographers frequently create:

Sketch maps of settlements

Diagrams of land-use zones

Annotated drawings of environmental features

These sketches support later cartographic production and help validate remotely gathered information.

Participant and Non-Participant Observation

In participant observation, the geographer takes part in local activities to gain an insider’s perspective. Non-participant observation involves watching and recording behaviors without direct involvement.

These techniques are widely used in cultural geography, urban studies, and research on social interactions in public spaces.

Technologies That Support Field Data Collection

Mobile GPS Devices

Modern fieldwork heavily relies on handheld and smartphone-based GPS tools, which provide accurate coordinates and allow geographers to:

A handheld GNSS receiver with an integrated map display is used to capture precise location data during field surveys. Devices like this are common in GIS-based fieldwork, where point locations, lines, and polygons are recorded directly into digital databases. The advanced professional features shown exceed AP requirements, but the image clearly illustrates how GPS tools support geographic data collection. Source.

Geotag photos, sketches, and notes

Map features while navigating various terrains

Record routes, distances, and time-stamped observations

Digital Sensors and Mobile Apps

Mobile data-collection apps improve efficiency and accuracy by standardizing data entry. They often include:

Drop-down menus for attribute selection

Automatic coordinate capture

Photo and audio integration

Cloud-based synchronization for team projects

These tools minimize errors associated with manual transcription.

Drones for Local-Scale Observations

Drones provide high-resolution imagery that complements on-site observation. While technically part of remote sensing, their low-altitude, targeted imagery often supports field data collection by offering perspectives not visible from the ground.

Individuals vs. Organizations in Field Data Collection

Field data may be collected by individual geographers, students, or community members conducting localized studies, or by organizations engaged in large-scale, systematic collection.

Individuals often contribute fine-grained, localized insights.

Organizations such as government agencies, NGOs, or research institutions generate standardized datasets across broader regions.

Together, these scales of data contribute to more comprehensive geographic understanding.

Integrating Field Data into Geographic Analysis

Field data is most powerful when integrated with other geographic sources, such as GIS layers, demographic datasets, or satellite imagery. It enhances analytical accuracy by:

Filling gaps where remotely sensed data lacks detail

Validating models or map features

Revealing small-scale patterns invisible at larger scales

Ground-truthing environmental and human geographic information

When geographers combine field data with other sources, they strengthen their ability to interpret complex spatial patterns and produce reliable, evidence-based conclusions about human and environmental processes.

FAQ

Geographers assess what type of information is needed—quantitative measurements, qualitative insights, or both—and then choose a method that most effectively produces that information.

They also consider:

Accessibility of the site

Time and resources available

The required level of precision

Whether human subjects are involved and if ethical clearance is needed

Combining multiple methods is common when studying complex environments or interactions.

Accuracy begins with calibrated instruments and standardised procedures. Geographers often take repeated measurements to minimise error.

They also:

Cross-check results using more than one instrument where possible

Record contextual details such as weather or time of day

Use consistent data entry formats to avoid transcription mistakes

Data that appears inconsistent is usually revisited or verified with additional field visits.

Local cultural norms can shape whether people are willing to participate in surveys or interviews. Geographers adapt their approach to respect community expectations.

For example:

Using culturally appropriate language or translators

Seeking permission from community leaders

Modifying observation methods to avoid intrusiveness

Awareness of these factors helps reduce bias and improves the quality of qualitative data.

Observer bias can arise when a geographer’s expectations influence what they notice or record. Selection bias may occur if only easily accessible locations are studied.

To reduce bias, geographers may:

Use predefined observation checklists

Sample multiple locations systematically

Pair qualitative notes with quantitative measures

Compare observations with independent data sources

Training and peer review of field notes also help maintain objectivity.

Field data is typically geocoded using coordinates recorded via GPS, then uploaded into GIS software where it can be mapped, layered, and analysed alongside other datasets.

Challenges include:

Ensuring consistent coordinate formats

Converting handwritten notes into digital form

Managing varying levels of precision from different instruments

Avoiding spatial errors during data entry

Careful data cleaning and validation are essential before analysis begins.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define field observation and explain one reason why it is important in geographic field data collection.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for a correct definition of field observation (systematic noting and recording of geographic phenomena in the real world).

• 1 mark for identifying a reason for its importance (e.g., provides firsthand, location-specific information).

• 1 mark for explaining how or why this reason matters (e.g., allows geographers to verify or complement secondary or remotely sensed data).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss two different methods that geographers use to collect field data. For each method, explain how it contributes to understanding spatial patterns or human–environment interactions.

Mark scheme:

• Up to 2 marks for accurately identifying two distinct field methods (e.g., direct measurement, surveys, interviews, field sketching, GPS-based data collection).

• Up to 2 marks for describing how each method works (1 mark per method).

• Up to 2 marks for explaining how each method contributes to understanding spatial patterns or human–environment interactions (1 mark per method).