AP Syllabus focus:

‘Spatial information also comes from written accounts: field observations, media reports, travel narratives, policy documents, interviews, landscape analysis, and photographic interpretation.’

Written and qualitative spatial information provides geographers with rich, descriptive insights into how people observe, interpret, and experience places, supporting deeper understanding of landscapes, patterns, and human–environment relationships.

Written and Qualitative Sources of Spatial Information

Written and qualitative sources supply descriptive, narrative, and interpretive forms of geographic data that complement numerical datasets. They help geographers analyze how individuals, communities, and institutions document and understand spatial patterns and landscapes. These sources do not rely on numerical measurements; rather, they offer contextual meaning, perception-based evidence, and place-based accounts that reveal how people interpret their surroundings.

Field Observations

Field observations are firsthand notes recorded during direct encounters with a landscape. They might include descriptions of land use, building types, vegetation, or cultural features. Because they reflect what an observer sees, hears, or senses in a location, they add detail that cannot always be captured by remote or quantitative technologies.

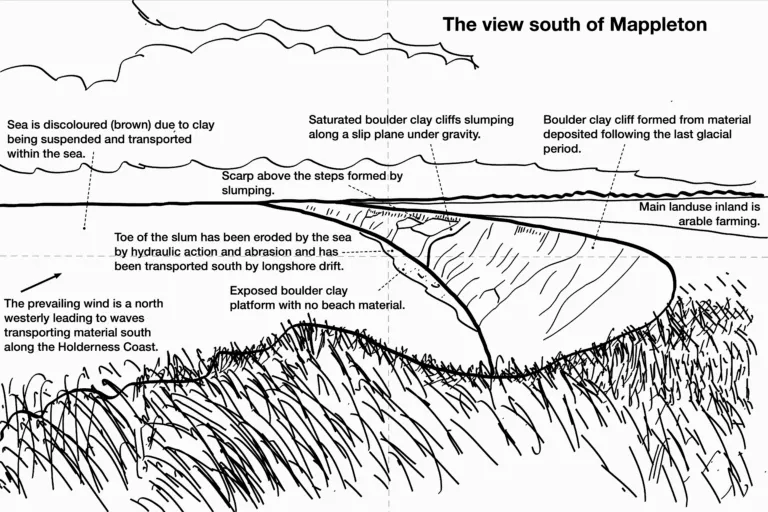

A coastal field sketch demonstrates how geographers record the visible features of a landscape in simplified form. Labels and brief annotations transform raw observation into qualitative spatial information that can later be compared with maps, statistics, or photographs. This sketch includes additional coastal-process terms and landforms beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but effectively illustrates how field sketches capture geographic meaning. Source.

Media Reports

Media reports serve as qualitative sources by documenting events, conditions, and issues across regions. Newspapers, digital articles, broadcasts, and investigative stories can reveal evolving spatial trends such as migration flows, environmental hazards, conflict zones, or economic changes. Their value lies in synthesizing multiple perspectives, though geographers must evaluate bias, reliability, and political framing.

Travel Narratives

Travel narratives describe personal experiences of movement through space. Historically, explorers, traders, and migrants recorded observations that became foundational geographic accounts. Modern narratives—blogs, videos, guidebooks—highlight how individuals interpret landscapes and cultural environments.

Travel Narrative: A descriptive account of a journey that documents experiences, landscapes, and cultural or spatial observations.

Travel narratives help geographers understand sense of place, perceptions of distance, and cultural interpretations of environments. They often reveal how people attach meaning to places, making them powerful tools for exploring place-making processes.

Policy Documents

Policy documents provide qualitative information created by governments, organizations, and planning agencies. These may include zoning codes, environmental assessments, transportation plans, or development proposals. They show how institutions envision future land use, regulate spatial arrangements, and respond to geographic challenges.

Key features often found in policy documents include:

Justifications for land-use decisions

Descriptions of environmental impacts

Statements of planning objectives

Maps and conceptual diagrams

Stakeholder priorities and negotiated outcomes

Policy documents offer insight into political and economic forces shaping regions, helping geographers analyze how decisions reflect broader societal values.

Interviews

Interviews capture voices, experiences, and perspectives from individuals or communities. They reveal how people understand their environment, identify problems, or interpret spatial changes.

Interview: A method of gathering qualitative data through guided conversation that elicits personal perspectives and spatial experiences.

Interviews help geographers understand lived experiences such as neighborhood change, cultural identity, accessibility, displacement, and environmental risk perception. They also illuminate variations in spatial knowledge across different groups.

Landscape Analysis

Landscape analysis involves interpreting the visible features of the built and natural environment to understand cultural and environmental processes. This form of qualitative observation allows geographers to assess how landscapes reflect patterns of development, cultural identity, economic activity, and ecological change.

Landscape analysis commonly examines:

Settlement forms and architectural styles

Agricultural layouts and rural land use

Transportation networks

Industrial and commercial zones

Cultural markers, signage, and iconography

Evidence of historical change or environmental modification

Landscape analysis is especially important for identifying spatial patterns that may not be documented through formal data sources.

Photographic Interpretation

Photographic interpretation uses images—taken from the ground, drones, or aircraft—to identify features, spatial relationships, and environmental conditions.

This satellite image of France shows contrasts between urban areas, agricultural regions, mountains, and coastlines that geographers can interpret by examining tone, texture, and pattern. Students can qualitatively assess spatial features such as urban concentration around Paris or vegetation distribution. Although it includes additional regional detail beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus, it effectively models imagery used for qualitative spatial interpretation. Source.

Photographic interpretation can reveal subtle patterns such as housing density, vegetation health, land-use changes, or signs of economic activity. When combined with field notes or interviews, it strengthens qualitative understanding.

Why Qualitative Sources Matter in Geography

Qualitative sources play an essential role in geographic inquiry because they illuminate how people experience and interpret space, not just how space is measured. They enrich spatial analysis by providing:

Contextual detail that quantitative data cannot capture

Human perspectives on issues such as migration, urbanization, and environmental change

Narratives of identity, belonging, and place

Descriptions of processes not easily visible in numerical datasets

Clues about values, attitudes, and cultural meanings associated with landscapes

By integrating written and qualitative sources with geospatial technologies and quantitative data, geographers achieve a more complete, meaningful understanding of spatial phenomena.

FAQ

Geographers assess reliability by cross-checking accounts with additional qualitative or quantitative data, ensuring that claims align with observable spatial patterns or documented events.

They also evaluate the author’s background, potential bias, date of publication, and intended audience.

To strengthen accuracy, researchers may triangulate information from multiple qualitative sources collected at different times or locations.

Useful field notes typically include precise descriptions of visible features, sketches, directional indicators, and comments on sounds, smells, or human activity.

Effective notes often:

Distinguish between objective observations and subjective impressions

Include quick annotations of spatial relationships

Highlight changes or anomalies that may require further investigation

Media reports often document events as they unfold, providing timely accounts that may appear before official datasets are produced.

They are particularly useful for:

Identifying emerging spatial patterns such as migration flows or environmental hazards

Understanding differing public narratives and interpretations of events

Tracing how geographic issues are framed by various political or social actors

Photographs allow geographers to identify built features, land-use types, signage, and spatial organisation that reflect cultural identities or processes.

Interpreting photographs helps researchers:

Detect subtle features such as architectural styles or boundary markers

Compare landscapes over time using repeated imagery

Assess the influence of cultural practices on the physical environment

Policy documents provide insight into planned or regulated spatial outcomes rather than individual perceptions or observations.

They are useful because they:

Reveal institutional priorities behind land-use decisions

Clarify long-term development strategies and zoning intentions

Identify stakeholders involved in shaping spatial change

These documents help geographers connect qualitative evidence to broader governance structures and planning processes.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which interviews can provide useful qualitative spatial information for geographers.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that interviews provide personal accounts, perspectives, or lived experiences of people in a place.

1 mark for explaining how these perspectives reveal information about spatial patterns, environmental perceptions, or social conditions.

1 mark for clearly linking interview data to a geographic insight (for example, understanding perceptions of neighbourhood change, accessibility, or land-use conflict).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how written and qualitative sources such as field observations, travel narratives, and media reports can contribute to a richer understanding of spatial patterns and landscapes.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing how field observations offer direct, descriptive evidence from the landscape.

1 mark for explaining how travel narratives provide experiential or cultural insights about place.

1 mark for explaining how media reports document current spatial issues or trends.

1 additional mark for using at least one appropriate example linked to any of the sources.

1 mark for demonstrating analysis by explaining how these qualitative sources complement or enhance other forms of spatial data (e.g., maps, statistics, satellite imagery).

1 mark for making a clear connection between qualitative information and improved interpretation of spatial patterns or human–environment interactions.