AP Syllabus focus:

‘Flows connect places through movement of people, goods, and ideas; distance decay describes how interaction often weakens with distance.’

Flows and distance decay explain how places interact across space, highlighting how movement patterns form, weaken, or intensify as distance, connectivity, and technology influence human and spatial relationships.

Understanding Flows in Human Geography

Flows are central to spatial interaction, describing the movement of people, goods, capital, and ideas between places. These movements shape geographic patterns and connect distant locations through networks of exchange.

Types of Geographic Flows

Human flows such as migration, commuting, and tourism link origins and destinations.

Economic flows include trade, investment, and supply chains.

Information flows encompass digital communication, media content, and knowledge transfer.

Cultural flows involve the spread of language, religion, and cultural practices.

Geographers examine these flows to understand how and why certain places become more connected, influential, or interdependent.

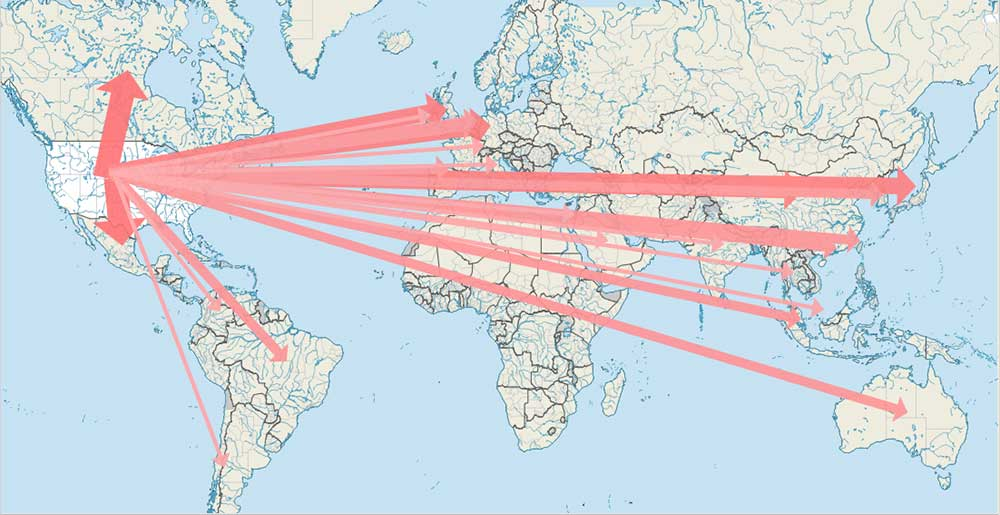

This radial flow map illustrates movements from a single origin in the United States toward destinations worldwide. The width of each red arrow shows the magnitude of interaction along each route. The basemap provides simple geographic context without introducing material beyond flows and spatial interaction. Source.

These interactions provide evidence of spatial processes that form regions, networks, and systems of exchange.

Spatial Interaction and Connectivity

Spatial interaction refers to the degree of contact between locations. It increases when transportation routes, communication systems, or economic ties strengthen connections. Improved connectivity often leads to:

Higher interaction frequency,

Faster movement of goods or information, and

Reduced friction of distance (hindrances caused by distance and accessibility).

As flows intensify through new technologies, the geographic world becomes increasingly integrated.

Introducing Distance Decay

Distance decay describes the diminishing intensity of interaction as distance increases between two places. It explains why nearby locations often have more frequent and consistent interactions than distant ones.

Distance Decay: The principle that interaction between two places decreases as the distance between them increases.

Distance decay provides a guiding framework for understanding how spatial behavior changes with distance.

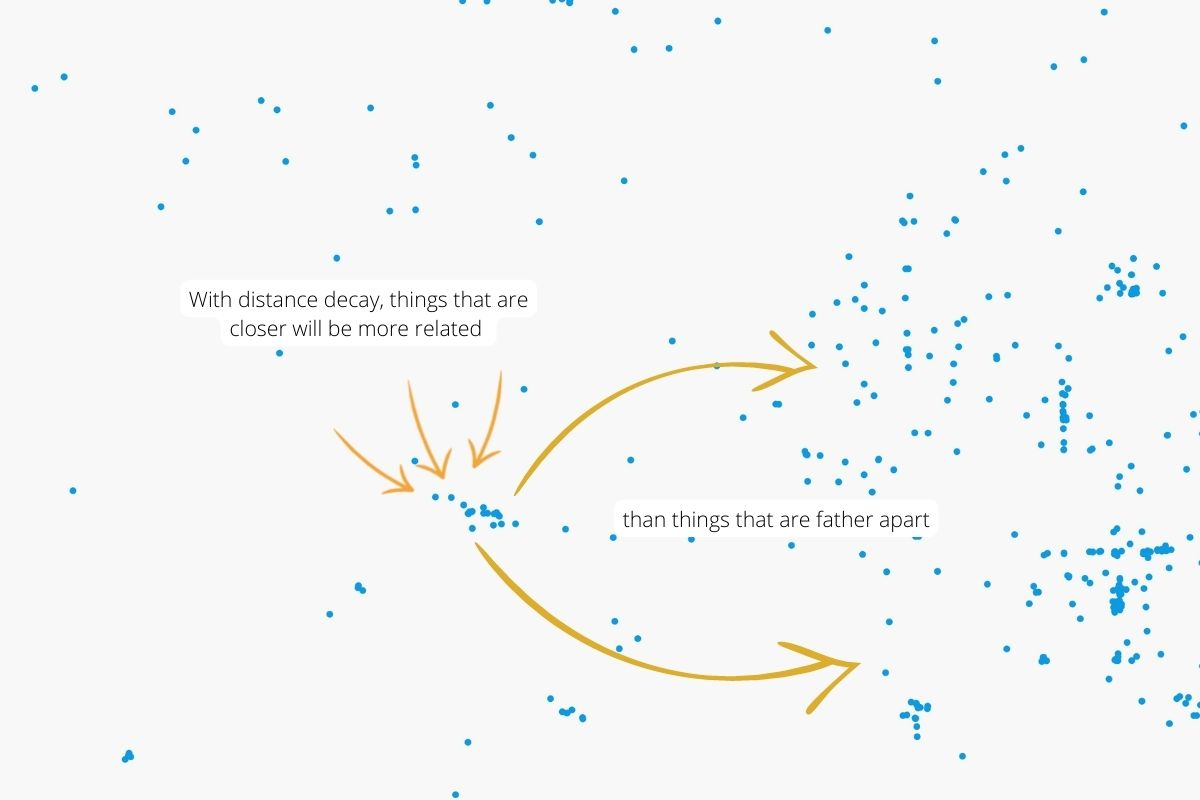

This diagram highlights distance decay by showing stronger relationships among nearby points and weaker connections with points farther away. The curved arrows emphasize how interaction diminishes across space. The brief on-image text reiterates this same concept without adding material outside the notes. Source.

A sentence separating blocks is required here, ensuring clarity before introducing equations.

= Level of interaction between two places

= Constant representing initial interaction strength

= Distance between locations (miles or kilometers)

= Exponent representing the rate of decay

Factors Influencing the Strength of Distance Decay

Distance decay does not operate uniformly; several geographic variables influence its rate and intensity.

Key Factors

Transportation networks: Better roads, airports, and transit systems slow the effect of distance decay by reducing travel time.

Communication technologies: Digital tools allow information to travel instantly, reducing the significance of physical distance.

Economic relationships: Strong economic ties between regions maintain flows even across great distances.

Cultural or historical connections: Shared heritage or migration networks keep distant places closely linked.

Political arrangements: Trade agreements, alliances, and border policies encourage or restrict interaction.

Patterns of interaction are shaped by how these forces enhance or limit connectivity across space.

Spatial Patterns Formed by Flows and Distance Decay

Geographers use flows and distance decay to understand key spatial patterns that appear on maps or in geographic data.

Clustering and Interaction Zones

Flows often create clusters of activity—areas with dense interactions, such as urban centers or trade hubs. These clusters develop where opportunities, accessibility, and economic activities concentrate.

Networks and Hierarchies

Flows frequently form networks, which are systems of interconnected nodes such as cities connected by transportation or communication lines. Within these networks, hierarchies emerge as some nodes function as global or regional centers, attracting more flows due to their size, accessibility, or influence.

Friction of Distance

Friction of distance represents the cost or effort required to move across space. As friction increases, distance decay becomes stronger. When friction decreases—through high-speed transit or digital communication—flows can expand across wider areas.

Changing Distance Decay in a Globalizing World

The modern world has transformed the traditional patterns of distance decay.

Global Connectivity

Air travel compresses distances, enabling high-volume flows across continents.

Digital communication links people instantly, reducing the relevance of physical separation.

Global supply chains create vast economic networks sustained across long distances.

These shifts weaken classical distance decay patterns in some sectors, but the principle remains useful for understanding many forms of human behavior.

Local Effects Persist

Despite global change, distance still matters in everyday geography. People choose nearby grocery stores, schools, and workplaces because proximity reduces time and cost. Social networks often remain strongest among people living near one another, illustrating that the effects of distance decay continue to shape human behavior at local scales.

Flows, Distance Decay, and Geographic Analysis

Understanding flows and distance decay helps geographers interpret spatial patterns, predict movement behavior, and explain how connections form or fade across space. These concepts support analyses of migration, trade, cultural diffusion, urban planning, transportation systems, and regional development, forming essential tools in AP Human Geography for examining the relationships between places.

FAQ

Geographers often combine quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate flow intensity. Common metrics include travel frequency, trade volume, digital communication rates, and transport network usage.

They may also use spatial interaction models, accessibility indexes, or mobility datasets to compare how easily people, goods, or information move between different locations.

In recent years, mobile phone data and online activity patterns have become valuable tools for mapping real-time flows at multiple scales.

Different flows experience decay at different rates because they respond to distinct barriers and incentives.

For example:

People may avoid long-distance travel due to time and cost, intensifying decay.

Goods can travel further if transport infrastructure is efficient.

Digital information has almost no friction, producing very weak decay patterns.

Cultural ties or historical migration links can also offset decay by maintaining strong interactions over long distances.

Globalisation weakens classic distance decay in many areas by improving long-distance transport and accelerating information exchange.

Air travel, container shipping, and digital platforms make distant places more accessible and cost-effective to connect with.

However, distance decay still applies to everyday behaviour such as school commutes, local shopping trips, and regional service use, showing that globalisation does not eliminate the principle entirely.

Cities with major transport hubs, economic specialisations, or global cultural influence often pull flows from far beyond their immediate region.

Key factors include:

International airports and seaports

Strong business networks or financial centres

Large migrant communities linking distant regions

Global cultural or media presence

These features reduce friction of distance by offering unique opportunities not available in smaller or less connected places.

Cultural diffusion often begins with strong interactions between nearby communities, reflecting rapid exchange over short distances.

As distance increases, the likelihood of regular contact declines, slowing the adoption of cultural traits such as language features, food traditions, or social practices.

Long-distance cultural exchange does still occur, but it is more dependent on migration networks, global media, and digital communication than on direct physical proximity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain the concept of distance decay and describe one real-world implication of this geographic pattern.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a clear definition of distance decay (interaction decreases as distance increases).

1 mark for identifying a valid real-world implication (e.g., people are more likely to shop, work, or socialise close to home).

1 mark for explaining why this implication occurs (e.g., increased cost, time, or effort reduces long-distance interactions).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of geographic flows, analyse how both technological developments and physical distance influence patterns of interaction between places.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying geographic flows (movement of people, goods, capital, or ideas).

1 mark for explaining how physical distance traditionally limits interaction through distance decay.

1–2 marks for explaining how technological developments such as transport or communication technologies reduce the effect of physical distance.

1–2 marks for analysing how these combined factors reshape spatial patterns, such as increased global connectivity, uneven flows, or changing regional relationships.