AP Syllabus focus:

‘Nature–society concepts include sustainability and how societies manage environmental limits while meeting human needs.’

Sustainability examines how human societies use and manage the environment while maintaining resources for the future, shaping the evolving nature–society relationship central to geographic inquiry.

Understanding the Nature–Society Relationship

The nature–society relationship refers to the dynamic ways humans interact with, depend on, modify, and conceptualize the environment. Geographers study this relationship to understand how environmental processes influence human activity and how human decisions reshape ecological systems. This relationship is never static; it shifts as technology, economies, cultures, and environmental conditions change.

Human Needs and Environmental Limits

Human societies rely on environmental systems for food, water, energy, and materials. However, these resources have environmental limits, meaning they can be depleted, degraded, or disrupted when used unsustainably. As populations grow and consumption increases, these limits become more visible in issues such as deforestation, groundwater depletion, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

Sustainability as a Geographic Concept

Sustainability is the guiding principle for balancing environmental limits with human needs. The term describes the capacity to use resources in ways that ensure long-term ecological health and continued availability for future generations.

Sustainability: The use of Earth’s resources in ways that do not constrain the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

Sustainability matters because the environment provides essential ecosystem services — such as water purification, climate regulation, and soil fertility — that humans cannot easily replace. A sustainable approach recognizes the interconnectedness of these systems.

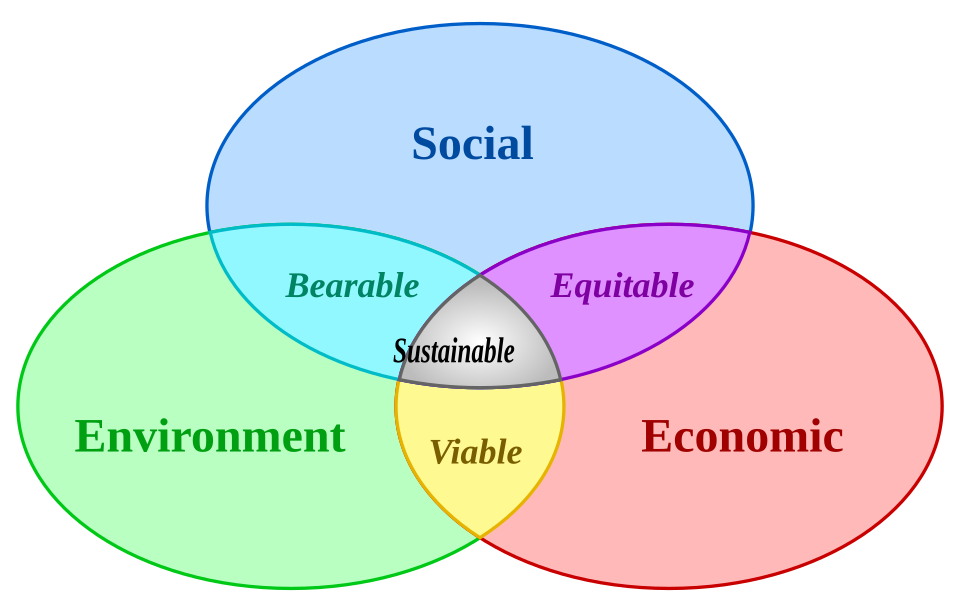

Sustainability is commonly framed around three interdependent pillars:

This Venn diagram illustrates sustainable development as the overlap of environmental, social, and economic systems. It reinforces the idea that long-term sustainability depends on balancing ecological health, social equity, and economic viability. The diagram also labels overlapping zones such as “equitable,” “bearable,” and “viable,” which provide helpful nuance beyond the minimum required by the syllabus. Source.

Environmental sustainability — maintaining ecological integrity and resource availability.

Economic sustainability — supporting long-term economic activity without degrading environmental assets.

Social sustainability — ensuring equity, well-being, and social cohesion across populations.

Interactions Between Society and the Environment

Environmental Management Strategies

Environmental management refers to how societies regulate, alter, and conserve natural systems. Strategies vary widely:

Conservation: Protecting resources through controlled use.

Preservation: Leaving natural areas untouched and restricting human use.

Restoration: Rehabilitating damaged environments.

Sustainable development planning: Integrating environmental considerations into policies, urban design, and economic decision-making.

These strategies influence landscapes, resource availability, and levels of human impact.

Cultural Views of Nature

Different cultures shape the nature–society relationship through their values and beliefs:

Some view nature as a resource to be used for economic growth.

Others emphasize stewardship, spiritual connections, or ecological balance.

Technologically advanced societies may rely on innovations to overcome environmental limits, while traditional societies may adapt closely to local ecosystems.

Cultural attitudes can affect the intensity of resource use, land-use patterns, and decision-making priorities.

Key Processes Connecting Sustainability and Society

Resource Use and Environmental Impact

Human consumption patterns directly shape sustainability outcomes. Geographers examine these patterns by analyzing:

Rate of resource extraction

Types of land use

Energy sources and efficiency

Waste production and management

These factors highlight how societies either respect or exceed environmental limits.

Unsustainable resource use often leads to:

Soil erosion and desertification

Habitat destruction

Water scarcity

Air and water pollution

Reduction of biodiversity

Sustainable practices, in contrast, aim to reduce these impacts through renewable energy, efficient water use, reforestation, and innovative urban planning.

This photo shows a residential high-rise in Bern, Switzerland, with one side of the building clad in solar panels that generate renewable electricity. It visually connects urban living with reduced dependence on fossil fuels, illustrating how cities can adapt the built environment to respect environmental limits. The image includes additional architectural and location details not required by the syllabus, but these provide useful real-world context for sustainable design. Source.

Feedback Loops in Human–Environment Systems

Human–environment interactions operate through feedback loops, where changes in one system create responses in another. For example:

Overfishing leads to declining fish populations, prompting stricter regulations.

Urban heat islands result from land-cover changes and may stimulate increased green-space planning.

These loops illustrate the reciprocal nature of environmental and societal processes.

Scales of Sustainability

Local Scale

Local governments and communities often address sustainability through:

Waste reduction initiatives

Local food systems

Community conservation projects

Green infrastructure and transportation planning

Local actions can respond quickly to environmental changes and community needs.

National Scale

At national scales, sustainability involves policies related to:

Energy production and emission standards

Environmental protection laws

National parks and protected areas

Resource regulation and economic planning

Governments must balance development goals with environmental protection.

Global Scale

Global sustainability addresses issues that cross borders, such as:

Climate change

Ocean health

Deforestation

International environmental agreements

Because environmental systems are interconnected, global cooperation is essential for managing shared resources.

The Importance of Long-Term Thinking

Sustainability requires long-term planning because environmental processes unfold slowly and cumulative impacts matter. Policies must consider future generations, long-term ecological resilience, and the ability of natural systems to recover from human use. Geographers emphasize this time horizon to help societies avoid exceeding environmental limits while meeting present needs.

FAQ

Geographers assess sustainability by comparing the rate of resource use with the rate of natural renewal or regeneration. A resource is considered sustainably used when extraction does not exceed its capacity to replenish.

They also analyse long-term trends in ecosystem health, such as soil fertility, biodiversity levels, and water quality, to determine whether current use is degrading environmental systems.

Additionally, geographers look at social and economic factors, including equitable access to resources and the viability of alternative technologies or practices.

Technological developments can reduce pressure on the environment by increasing efficiency or enabling cleaner alternatives, such as renewable energy or precision agriculture.

However, some technologies intensify resource use by enabling more intensive extraction or consumption. This dual potential means technology can strengthen or weaken sustainability, depending on how societies deploy it.

Geographers therefore examine technology not in isolation, but in relation to cultural values, economic systems, and environmental limits.

Urban areas often face greater challenges with pollution, waste management, and energy demand, but they also benefit from efficient infrastructure, public transport, and concentrated services.

Rural environments may have more direct access to natural resources and lower population densities, but face issues such as land degradation, deforestation, and limited environmental regulation.

Both settings require tailored sustainability strategies shaped by local environmental conditions, economic structures, and cultural attitudes.

Cultural beliefs shape how societies perceive the value of nature, influencing behaviours such as conservation, resource extraction, and land management.

For example, communities with strong stewardship traditions may prioritise long-term ecological health, while others may emphasise economic growth over environmental protection.

These cultural frameworks affect everything from household consumption patterns to national environmental policy, making them central to understanding sustainability outcomes.

Qualitative data such as interviews, field observations, and policy documents help geographers capture local perspectives on environmental issues and the lived experiences of resource users.

This type of data reveals motivations, cultural attitudes, and social inequalities that quantitative data alone cannot show.

Geographers often combine qualitative insights with spatial or environmental data to better understand how sustainability challenges vary across places and communities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain what geographers mean by the term sustainability in the context of the nature–society relationship.

Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying that sustainability involves meeting present human needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.

• 1 mark for linking sustainability to responsible or balanced use of environmental resources.

• 1 mark for recognising its role in shaping the nature–society relationship (for example, acknowledging interactions between human activities and ecological systems).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how environmental limits shape human decision-making and influence the long-term sustainability of societies at different scales.

Question 2

• 1 mark for identifying the concept of environmental limits (for example, finite resources, ecosystem thresholds, carrying capacity).

• 1 mark for explaining how these limits influence human decisions (for example, policies on resource management, conservation strategies, or technological innovations).

• 1 mark for providing at least one accurate example at a local, national, or global scale.

• 1 mark for explaining how environmental limits affect sustainability outcomes (for example, preventing overuse, encouraging renewable energy adoption).

• Up to 2 additional marks for analytical depth, such as comparing scales, evaluating consequences, or linking feedback between human decisions and environmental systems.