AP Syllabus focus:

‘Forced migrations include slavery and events that produce refugees, internally displaced persons, and asylum seekers.’

Forced migration reshapes populations by compelling people to move under threats to their safety, freedom, or survival. These movements reflect extreme pressures and reveal global political, social, and environmental vulnerabilities.

Understanding Forced Migration

Forced migration occurs when individuals or groups relocate without meaningful choice, typically due to coercion, violence, or life-threatening conditions. Geographers examine how these movements vary across regions and how they reflect different types of displacement recognized in global frameworks.

Forced Migration: The movement of people in which coercive factors, such as violence, persecution, or environmental disasters, make relocation involuntary.

Forced migration contrasts with voluntary migration because migrants act under duress rather than opportunity. This distinction is central to interpreting global population patterns and the changing composition of societies experiencing inflows or outflows of displaced populations.

Slavery as a Form of Forced Migration

Historical Foundations of Slavery

Slavery represents one of the earliest large-scale forms of forced migration.

Slave ship model showing the internal decks used to transport enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. The cross-section highlights how people were confined in tightly packed spaces, emphasizing the coercive and inhumane nature of this form of forced migration. The museum display includes extra interpretive text and artifacts not required by the syllabus but useful for additional historical context. Source.

The transatlantic slave trade, one of the most significant forced migration events, moved millions of Africans to the Americas.

Slavery shaped demographic patterns by concentrating displaced populations in plantation economies and altering cultural landscapes across continents.

Although legal slavery has been abolished in most countries, modern forms of forced labor, including human trafficking, still produce coerced displacement.

Slavery illustrates how forced migration can result in long-lasting demographic, cultural, and political consequences, persisting long after the system that generated the movement ends.

Refugees

Defining Refugees in Human Geography

Refugees are among the most internationally recognized categories of displaced populations. Their movement represents a response to extreme threats, often tied to regional instability.

Refugee: A person who crosses an international border to escape persecution, conflict, or violence, and who cannot safely return home.

Refugees are protected under international law, particularly the 1951 Refugee Convention, which requires states to offer non-refoulement, meaning individuals cannot be returned to places where their lives are at risk. Political, environmental, and cultural contexts shape refugee flows, and their distribution affects the services and policies of receiving countries.

Refugee movements often occur in large waves, creating immediate pressures on infrastructure, housing, and humanitarian organizations in destination regions.

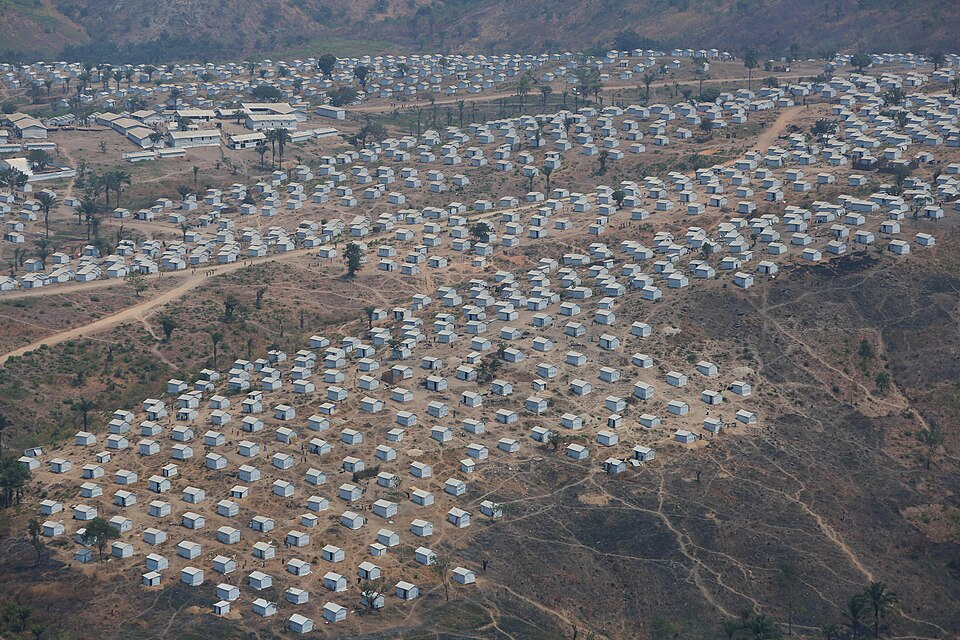

Aerial view of Lusenda refugee camp, where rows of shelters extend across the landscape in a dense, planned pattern. The image demonstrates how large concentrations of refugees create new settlement forms requiring significant infrastructure and coordinated humanitarian support. The specific camp location and layout provide additional context beyond the syllabus but help visualize real-world refugee spatial organization. Source.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

Characteristics of Internal Displacement

IDPs represent one of the fastest-growing and most understudied categories of forced migrants. Unlike refugees, IDPs do not cross borders, but they flee similar dangers.

Internally Displaced Person (IDP): An individual forced to move from their home due to conflict, persecution, or disaster, but who remains within their country’s borders.

IDPs frequently face heightened vulnerability because they remain in unstable regions and often lack the same level of international legal protection as refugees.

Internally displaced persons’ camp in South Darfur, Sudan, where residents have constructed temporary shelters from sticks and plastic sheets. The image highlights how IDPs remain within national borders yet live in unstable, resource-poor environments shaped by conflict. The specific location offers extra detail beyond syllabus requirements but effectively visualizes typical IDP settlement patterns. Source.

Their displacement may be caused by civil war, gang violence, development projects, natural disasters, or political repression.

IDPs also influence internal population patterns by generating sudden shifts in urbanization, resource needs, and regional demographics.

Asylum Seekers

Understanding Claims for Protection

Asylum seekers move across borders like refugees but have not yet been legally recognized as such. Their experiences highlight the complexities of international migration systems.

Asylum Seeker: A person who applies for legal refugee status after crossing an international border, seeking protection from harm in their country of origin.

Asylum processes vary widely by country, and acceptance rates depend on political conditions, legal structures, and public opinion. While applications are reviewed, asylum seekers may face restricted access to employment, movement, or public services.

Their presence impacts receiving countries by shaping debates over immigration, humanitarian responsibility, and national identity.

Key Drivers of Forced Migration

Although each category of forced migrant is legally distinct, common driving forces underlie their movement:

Armed conflict: Civil wars, ethnic violence, and political instability produce both refugees and IDPs.

State persecution: Targeting of groups based on race, religion, ethnicity, or political affiliation often results in cross-border flight.

Environmental disasters: Floods, droughts, earthquakes, and climate-related hazards displace millions annually.

Human rights violations: Systemic oppression, forced labor, and trafficking compel individuals to migrate involuntarily.

Development projects: Large infrastructure projects, such as dams or mining operations, can displace communities internally.

These drivers reveal how forced migration reflects broader structural conditions, including governance, resource pressures, and geopolitical conflicts.

Spatial Patterns and Global Implications

Forced migrants reshape regional and international geographies. Concentrations of refugees in border regions create humanitarian zones, while IDP camps alter internal settlement patterns. Receiving countries must adjust to demographic changes, service demands, and evolving cultural landscapes. Forced migration also influences political relationships, international negotiations, and global humanitarian networks.

Understanding slavery, refugees, IDPs, and asylum seekers allows geographers to analyze how forced migration continues to transform societies and intensify debates about protection, borders, and human rights.

FAQ

Eligibility is assessed through a formal process called refugee status determination, which evaluates whether the applicant faces a credible threat of persecution based on specific grounds such as ethnicity, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership of a social group.

Applicants must present evidence, oral testimony, or documentation.

Interviewers also consider country-of-origin reports to verify the plausibility of the applicant’s claims.

Refugee camps are typically placed near borders to allow rapid humanitarian access and minimise transport requirements during emergencies.

Camp design often considers:

• Land availability and environmental suitability

• Access to water sources and sanitation

• Security concerns and separation from conflict zones

• Space for health, education, and food distribution facilities

Governments may limit movement or work rights while claims are processed to maintain administrative control and reduce perceived pull factors.

Some restrictions stem from concerns about labour market impacts, public opinion, or national security.

However, such limits can lead to long waiting periods in temporary accommodation and reduced self-sufficiency for asylum seekers.

Neighbouring countries often experience spillover pressures even if they do not host large refugee populations.

These may include:

• Increased border security requirements

• Humanitarian transit needs for those passing through

• Economic impacts on cross-border trade

• Tensions over resource use in frontier regions

IDPs may struggle with protracted displacement, often living in temporary shelters for years due to ongoing insecurity or slow reconstruction.

Challenges frequently include:

• Lack of legal documentation, hindering access to services

• Difficulty reclaiming property or land

• Limited employment opportunities in host regions

• Persistent psychological effects from conflict or disaster

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why internally displaced persons (IDPs) often face greater vulnerability than refugees.

(1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., lack of international legal protection, remaining within conflict zones).

1 mark for explaining how this increases vulnerability (e.g., limited access to humanitarian aid, continued exposure to violence).

1 mark for additional detail or contextual development (e.g., government restrictions, weak institutional capacity).

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how different types of forced migration (slavery, refugees, IDPs, and asylum seekers) create distinctive spatial and social impacts on both origin and destination regions.

(4–6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for correctly describing at least two types of forced migration (e.g., slavery as historical forced labour; refugees crossing borders to escape persecution; IDPs displaced internally; asylum seekers awaiting refugee status determination).

Up to 2 marks for explaining spatial impacts (e.g., population redistribution, camp formation, pressures on infrastructure, changes in settlement patterns).

Up to 2 marks for explaining social impacts (e.g., service demands, cultural change, social tension, trauma and vulnerability).

High-mark responses will reference specific examples and show clear analytical links between the type of forced migration and its distinct outcomes.