AP Syllabus focus:

‘Types of voluntary migration include chain and step migration, which describe how social connections and stages shape movement patterns.’

Chain and step migration illustrate how migrants rely on existing social ties and sequential movement stages, shaping spatial patterns, community structures, and demographic change across regions.

Understanding Migration Networks

Migration networks are systems of social connections, relationships, and communication links that influence where and how people move.

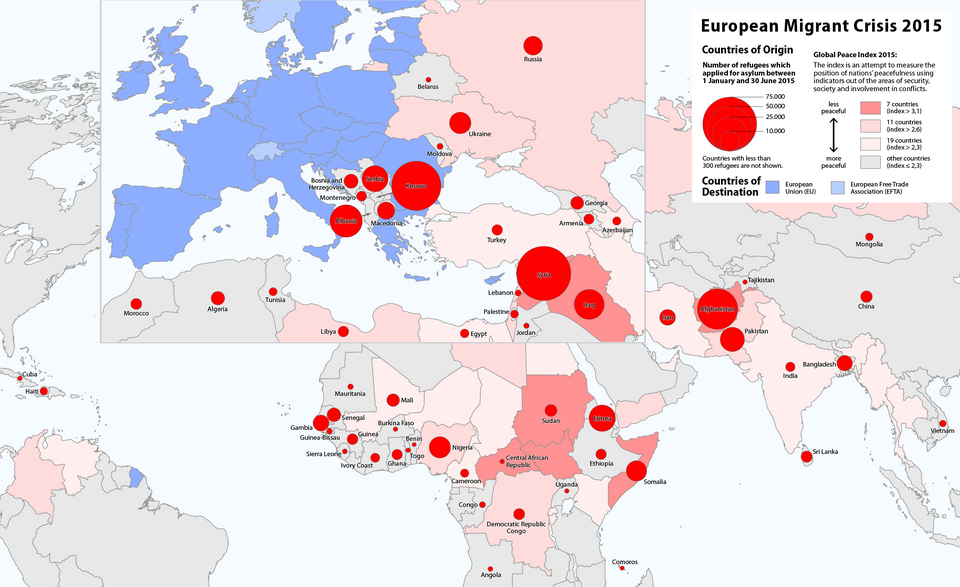

European Migration Flows, 2015. This map shows the countries of origin of asylum seekers during the 2015 European migrant crisis and highlights the main destinations in Europe. It includes additional detail on refugee origins and magnitudes that go beyond chain and step migration but supports understanding of how migration networks shape spatial patterns of movement. Source.

Chain Migration

Chain migration occurs when migrants follow family members, friends, or community contacts to a destination where these social connections already exist. This process demonstrates how social networks reduce the risks, uncertainties, and costs associated with migration.

Chain Migration: The process by which migrants follow established social ties—such as relatives or community members—to a destination previously settled by people from the same origin.

Chain migration expands migrant communities over time through interpersonal links rather than solely through economic or political forces.

How Chain Migration Works

Chain migration generally relies on communication, trust, and social support. These connections influence both the decision to move and the choice of destination. Migrants often receive help from earlier arrivals in forms such as guidance, job leads, and temporary housing.

• Early migrants establish a foothold in a new place, creating a foundation for future arrivals

• Information about living conditions, employment, and legal procedures circulates back to the origin

• Later migrants experience fewer barriers due to established support networks

• Migrant enclaves—neighborhoods with high concentrations of a particular ethnic or cultural group—frequently emerge through repeated chains

Why Chain Migration Matters

Chain migration helps geographers understand the clustered spatial patterns of immigrant populations across cities and regions.

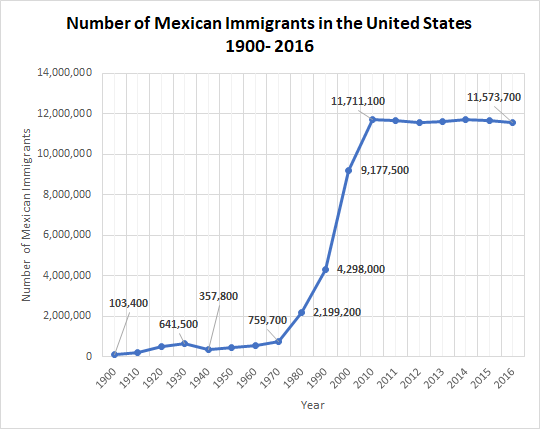

Mexican Immigration to the United States, 1900–2016. This graph shows the growth of the Mexican-born population residing in the United States, reflecting sustained migration links between Mexico and U.S. destinations. The figure includes detailed numerical values and time periods that go beyond the specific AP Human Geography syllabus but serves as a clear example of how migration networks support long-term migration streams. Source.

Step Migration

Step migration refers to the process in which migrants move in a series of smaller, less dramatic stages toward a final destination instead of relocating in one long-distance move.

Step Migration: A migration pattern in which movement occurs through a sequence of progressively larger or more distant locations before reaching the final destination.

Rather than moving directly from a rural village to a major global city, migrants may pass through intermediate towns and regional centers.

How Step Migration Occurs

Step migration reflects both opportunities and constraints encountered along the migration path. These incremental stages are shaped by migrants’ access to resources, transportation networks, and legal or economic barriers.

• Migrants begin in small local steps, such as moving from rural areas to nearby towns

• As opportunities increase, migrants progress to larger urban centers

• Each stage brings new skills, savings, or knowledge, enabling further movement

• The final stage may involve national or international relocation

The Role of Intervening Factors in Step Migration

At each stage of movement, migrants encounter intervening opportunities—favorable conditions that may encourage them to settle before reaching the intended destination. Conversely, intervening obstacles—political, economic, or physical barriers—may delay or prevent further movement. These factors highlight that step migration reflects both aspiration and adaptation.

Comparing Chain and Step Migration

Although chain and step migration are distinct processes, both help explain the complexity of voluntary migration patterns. Each emphasizes different forces shaping migrant decision-making:

• Chain migration stresses social networks, highlighting the role of interpersonal ties

• Step migration focuses on incremental movement, emphasizing the staged nature of relocation

Both processes reveal that migration is rarely a simple one-time decision. Instead, it unfolds through interactions among social connections, economic choices, and spatial opportunities.

Spatial Patterns and Community Outcomes

Places influenced by chain and step migration experience new population dynamics and cultural landscapes:

• Expansion of migrant enclaves due to chain migration strengthens cultural preservation

• Growth of urban centers through step migration increases economic specialization and labor supply

• Changes in language use, religious practices, and cultural traditions reshape local identity

• Regional governments often respond by developing policies related to housing, integration, and employment

Why These Concepts Matter for AP Human Geography

Understanding chain and step migration helps students analyze migration not only as an individual act but as a structured process shaped by networks and stages. These concepts clarify why migration streams are patterned, how communities evolve over time, and why destinations vary by migrant group.

Migration networks demonstrate that voluntary migration is a socially embedded phenomenon influenced by both interpersonal ties and sequential decision-making.

FAQ

Modern communication technologies strengthen migration networks by enabling instant contact between migrants and those at the origin. This reduces uncertainty and accelerates decision-making.

Messages about job openings, housing options, and legal procedures spread rapidly, making potential migrants more confident about moving.

Mobile banking, remittances, and messaging apps also allow migrants to support new arrivals more effectively, expanding the scale and reach of chain migration.

Enclaves endure when they provide persistent economic, social, and cultural advantages, such as specialised labour markets, community institutions, and shared language environments.

They tend to fade when assimilation pressures increase, opportunities expand outside the enclave, or when younger generations disperse for education or employment.

Local policy and urban development decisions can also alter enclave viability through zoning, redevelopment, or housing availability.

Migrants with limited financial resources or restricted access to long-distance travel often rely on step migration to move gradually.

This pattern is common among rural-origin migrants who must accumulate savings, skills, or documentation at each stage.

Younger migrants may also follow stepwise paths as they pursue education or employment opportunities that lead them from local towns to regional and then national hubs.

Family reunification policies explicitly allow close relatives of legal residents to migrate, directly reinforcing chain migration.

Even policies not directly related to family migration may unintentionally strengthen migration networks when they enable stable settlement, such as work visas that offer pathways to permanent residency.

Over time, these frameworks increase the number of legally residing migrants who can sponsor relatives, expanding migration chains without intentional policy design.

Migrants often confront uneven employment prospects at each stage, forcing them to adjust their plans or extend their stay longer than expected.

Common challenges include:

• Navigating unfamiliar legal systems or documentation requirements

• Securing affordable housing in transitional urban areas

• Balancing temporary work with long-term relocation goals

Environmental barriers, transport limitations, or social discrimination can further complicate movement between stages.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain the concept of chain migration and describe one way it can influence the spatial distribution of immigrant communities.

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for a correct definition of chain migration (e.g., migrants following family or community members to an established destination).

• 1 mark for identifying an influence on spatial distribution (e.g., formation of ethnic enclaves, clustering of migrant communities).

• 1 mark for explaining the influence (e.g., support networks encourage further migrants to settle in the same area, reinforcing concentration).

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how step migration operates as a staged movement process and evaluate how intervening opportunities or obstacles can alter a migrant’s intended final destination.

(4–6 marks)

• 1 mark for a clear definition or description of step migration as a staged or incremental movement.

• 1–2 marks for explanation using accurate examples (e.g., rural to town, town to city, city to another country).

• 1–2 marks for analysis of intervening opportunities or obstacles (e.g., availability of jobs, legal restrictions, transport limitations).

• 1 mark for evaluation of how these factors may redirect, delay, or halt the intended final movement.