AP Syllabus focus:

‘An aging population has political, social, and economic consequences, including impacts linked to the dependency ratio.’

An aging population reshapes how societies function by altering workforce composition, straining public services, and transforming political priorities, creating long-term impacts on economies, communities, and demographic structures.

Political, Social, and Economic Consequences of an Aging Population

Understanding Aging Populations

An aging population refers to a demographic condition in which the proportion of individuals aged 65 and older increases relative to younger age groups. This shift results primarily from declining birth rates, rising life expectancy, or both. As populations age, the balance between people in the workforce and those classified as dependents changes, producing wide-ranging consequences that influence governance, public spending, social dynamics, and economic productivity.

The dependency ratio is central to understanding these consequences because it measures the number of dependents supported by the working-age population. A higher dependency ratio reflects greater pressure on society to provide for non-working individuals.

Dependency Ratio: The number of dependents (young and elderly) compared to the working-age population, often expressed per 100 working-age people.

An aging population typically increases the elderly dependency ratio, intensifying financial and social responsibilities for governments and working-age adults.

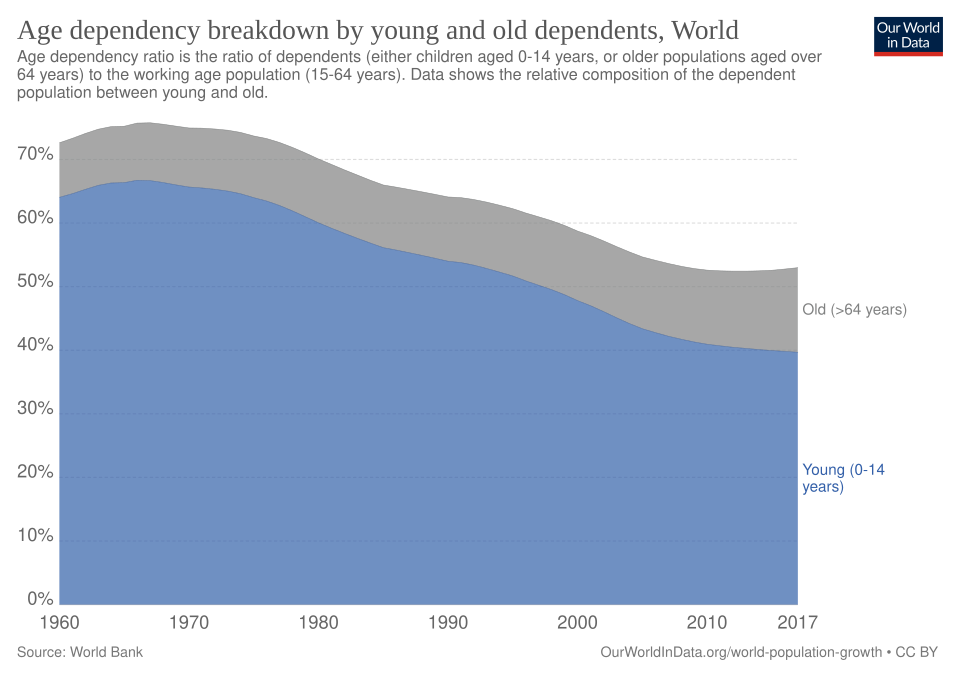

As the proportion of older dependents rises relative to working-age adults, the dependency ratio—especially the old-age dependency ratio—increases, meaning fewer workers support more retirees.

This chart shows how the global dependency ratio is divided between young and older dependents. Students can observe the rising proportion of older dependents as evidence of population aging and growing fiscal pressures. The chart includes extra numerical projections not required by the AP syllabus but still supports conceptual understanding. Source.

Political Consequences of an Aging Population

A demographic shift toward older age groups influences political systems, policy priorities, and electoral outcomes.

Key political impacts include:

Shift in voting power: Older adults often vote at higher rates than younger groups, amplifying their political influence. As their share of the population grows, political platforms frequently shift toward issues such as pensions, medical care, and age-related services.

Policy reorientation: Governments increasingly prioritize health care funding, retirement security, and long-term care infrastructure due to rising demand from elderly citizens.

Budgetary constraints: More public spending is allocated to age-related programs, potentially reducing government capacity to invest in education, innovation, or infrastructure.

Immigration debates: Because immigration can supplement the workforce and reduce labor shortages, governments may adjust immigration policies. However, political tensions can arise over how and whether migration should be used to address demographic challenges.

Social Consequences of an Aging Population

Social structures and community dynamics shift significantly as the proportion of older residents increases.

Major social impacts include:

Changing household structures: More single-person elderly households increase demand for assisted-living facilities, senior housing, and specialized transportation.

Pressure on caregiving systems: Families experience rising caregiving responsibilities for aging parents, which can influence household income, job participation, and overall well-being.

Health care demand: Societies require expanded geriatric care, chronic disease management, and long-term care services. Health systems must adapt by increasing staff, facilities, and resources dedicated to older adults.

Intergenerational interactions: As demographic patterns shift, relationships between age groups evolve. Youth may shoulder greater tax burdens, while older adults require more services, potentially generating social tension if resources become limited.

One key social outcome is increased attention to age-friendly communities, designed to promote accessibility, mobility, and engagement for older adults.

Economic Consequences of an Aging Population

Economic impacts are among the most immediate and profound consequences of demographic aging. The structure of the labor force, productivity patterns, and public finance systems all experience significant change.

Key economic consequences include:

Labor shortages: As more adults retire, the workforce shrinks relative to labor demand, particularly in sectors reliant on younger workers.

Increased dependency burdens: A rising elderly dependency ratio requires a smaller working-age population to support a larger non-working population through taxes and contributions to pension systems.

Higher public expenditures: Governments must allocate larger portions of national budgets to pensions, health care, and long-term care. These rising costs can lead to increased taxation or reallocation of funds away from other sectors.

Slower economic growth: Reduced labor force participation may limit productive capacity, contributing to slower GDP growth.

Shifts in consumer markets: Older populations spend differently than younger groups. Demand increases for pharmaceuticals, medical devices, health services, and senior-friendly products, while markets such as education or youth-oriented goods may decline.

Pressure on pension systems: Many pension programs were designed when life expectancy was lower. As people live longer, retirement benefits must be paid out for more years, creating funding challenges.

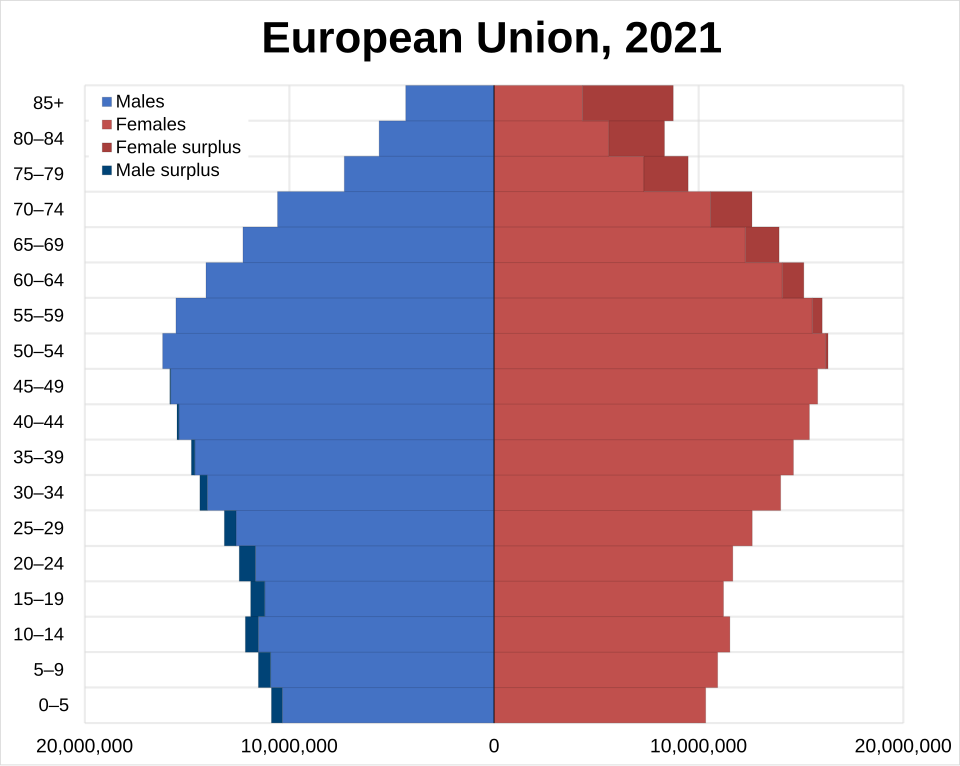

In many high-income regions, population pyramids now look more like rectangles or even are top-heavy, with large cohorts of people in their 60s, 70s, and 80s compared with smaller younger cohorts.

This population pyramid shows a narrow base and broad upper age groups, demonstrating the demographic shape of an aging population. It helps students understand how a large senior population increases the old-age dependency ratio and reshapes societal needs. The chart includes detailed EU-specific percentages not required by the AP syllabus but useful for interpreting real-world pyramids. Source.

Interconnected Impacts and Future Considerations

The political, social, and economic effects of an aging population interact with one another. For example, political decisions about pension reform shape economic conditions, while social changes in caregiving influence workforce participation. Understanding these connections helps geographers assess how aging reshapes landscapes, service demands, and population distribution patterns.

Global regions experience aging differently, and responses vary by culture, economic development, and government structure. However, the overarching consequences—political pressure, social restructuring, and economic strain—remain consistent across contexts, aligning with the syllabus focus on how aging populations transform societies through impacts linked to the dependency ratio.

FAQ

Areas with high concentrations of older residents often see a shift in service provision, with more investment in local healthcare centres, rehabilitation facilities, and accessible transport.

Urban areas may also retrofit infrastructure for mobility needs, while rural regions with depopulation may struggle to maintain sufficient services.

Local governments sometimes redirect funding from education or youth-focused amenities to facilities that support independent living for older adults.

Social cohesion tends to be stronger when governments provide adequate pensions, healthcare, and support for caregivers, reducing strain on younger generations.

Intergenerational tension is more likely when the tax burden is perceived as unequal or public spending favours older groups at the expense of youth-oriented investments.

Cultural attitudes toward ageing also matter; societies with strong norms of filial responsibility often experience less conflict.

Housing demand often shifts towards smaller, accessible homes, retirement communities, and assisted-living accommodation.

In some regions, older homeowners remaining in large family homes reduce availability for younger families, contributing to shortages and rising prices.

Governments may promote downsizing incentives or encourage the construction of age-friendly housing to balance the market.

Fiscal strain depends on the structure of pension systems, the proportion of informal labour, and the tax base available to support retirees.

Countries with pay-as-you-go pension schemes often face more pressure because current workers directly fund pension payments.

Nations with strong sovereign wealth funds or high immigration can reduce long-term strain by supplementing revenue or replenishing the workforce.

Governments may implement multiple strategies, including:

Increasing retirement ages to align with longer life expectancy.

Expanding preventative healthcare to reduce costly chronic illness.

Encouraging higher labour-force participation, especially among women and older adults.

Some governments also invest in automation and productivity-enhancing technologies to offset labour shortages in essential sectors.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain one social consequence of an ageing population.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid social consequence (e.g., increased demand for elderly care services, pressure on family caregivers, rise in single-person elderly households).

1 mark for explaining how or why this consequence occurs (e.g., because a growing share of older adults requires more support, care, and age-specific services).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Assess the economic impacts of an ageing population on a developed country. In your answer, refer to both challenges and possible benefits.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least one economic challenge (e.g., higher public spending on pensions and healthcare, labour shortages).

1 mark for explaining why this challenge occurs (e.g., fewer working-age adults contribute taxes while more retirees draw benefits).

1 mark for identifying at least one potential economic benefit (e.g., growth in industries serving older adults, such as healthcare or leisure).

1 mark for explaining how this benefit arises (e.g., increased demand for certain goods and services creates new markets and employment opportunities).

1 mark for an overall assessment that weighs challenges and benefits or comments on the extent of the economic impact.