AP Syllabus focus:

‘Suburban sprawl increases land consumption and car dependence, making it harder to manage energy use, emissions, and infrastructure demands.’

Suburban sprawl reflects low-density, outward urban expansion that reshapes land use, infrastructure needs, and environmental impacts across metropolitan regions.

Understanding Suburban Sprawl as a Sustainability Issue

Suburban sprawl is a form of low-density, automobile-dependent urban expansion that spreads development outward from a city’s core. It raises concerns because it increases land consumption, infrastructure demands, and environmental pressures that challenge long-term urban sustainability. These patterns influence how residents travel, how cities allocate resources, and how metropolitan regions manage growth.

When suburban sprawl occurs, disconnected subdivisions, commercial strips, and isolated employment zones expand across formerly rural land. These spatial patterns limit walkability and strengthen reliance on private vehicles.

Key Characteristics of Suburban Sprawl

Low-Density Development

Low-density development refers to residential or commercial land uses with relatively small numbers of people or structures per unit of land.

Low-Density Development: A land-use pattern characterized by dispersed buildings, large lots, and a small population per unit of area.

This form of development spreads housing across large areas, reducing the efficiency of transportation and public service networks.

Separation of Land Uses

Many sprawling regions separate residential, commercial, and industrial zones, often enforcing this separation through zoning regulations. This separation makes daily activities—shopping, commuting, schooling—geographically farther apart.

Car dependence intensifies as residents must rely on automobiles to access dispersed destinations.

Automobile Orientation

Sprawl typically creates landscapes structured around wide roads, parking lots, and long travel distances.

Increased vehicle miles traveled (VMT) intensifies emissions and energy use.

Road expansion, highway interchanges, and parking infrastructure reshape metropolitan land use.

Transit systems struggle to serve spread-out populations efficiently.

Why Suburban Sprawl Is a Sustainability Issue

Increased Land Consumption

Sprawl converts agricultural land, forests, and open spaces into low-density development. This creates ecological fragmentation and reduces the land available for conservation, farming, or watershed protection.

Compared with compact, mixed-use cities, sprawling suburbs use much more land per person and require longer infrastructure networks for roads, pipes, and power lines.

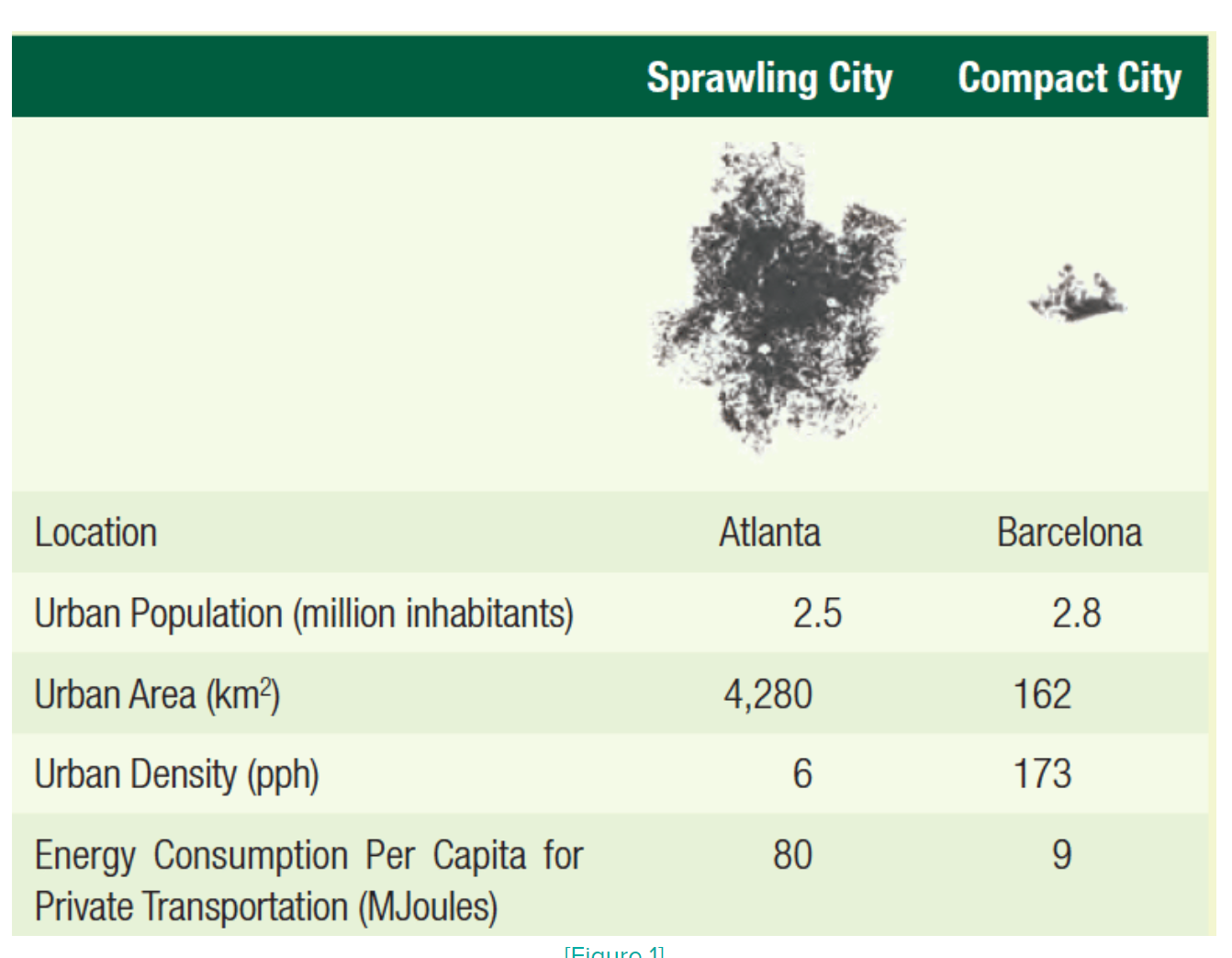

This diagram compares a sprawling city with a compact city that has a similar population but occupies far less land. It visually reinforces how suburban sprawl increases land consumption, infrastructure needs, and energy demand per resident compared with a denser, transit-supportive urban form. Source.

Car Dependence and Energy Use

Car dependence raises demand for fossil fuels, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing cities’ ability to meet sustainability goals. Longer commutes and limited transit alternatives strengthen reliance on nonrenewable energy sources.

Infrastructure Strain

Sprawl requires more infrastructure per person than compact development. Low-density patterns demand:

Longer water and sewer lines

Expanded road networks

Larger energy grids

Additional stormwater systems

Because infrastructure must be stretched across greater distances, the cost per resident increases and long-term maintenance becomes more difficult.

Environmental Impacts of Suburban Sprawl

Air Pollution and Emissions

Automobile reliance leads to higher emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter.

Traffic congestion worsens during peak hours.

Poor air quality increases respiratory health risks.

Region-wide emissions grow as commuting distances expand.

Water Use and Runoff

Sprawl increases impervious surfaces—roads, driveways, parking lots—which reduce groundwater recharge and increase runoff.

Runoff carries pollutants into streams and lakes.

Flood risks increase when natural land cover is replaced with pavement.

Low-density lawns and landscaping typically require greater water use.

Loss of Biodiversity

As metropolitan areas spread outward, wildlife habitats become fragmented. Species that depend on large, connected habitats face heightened pressures.

Social and Economic Dimensions

Uneven Access and Car Dependence

Sprawling regions often create inequitable access to jobs and services.

Residents without cars face limited mobility.

Transit-dependent populations—youth, elderly adults, and low-income groups—may be isolated from schools, healthcare, or employment centers.

Infrastructure and Fiscal Stress

Local governments experience financial strain as they attempt to maintain extensive networks of roads, utilities, and public facilities dispersed across wide areas.

Maintenance costs rise faster than tax revenue in many suburban jurisdictions.

Low-density development does not generate enough economic activity to support its long-term infrastructure obligations.

Processes That Drive Suburban Sprawl

Economic and Demographic Drivers

Demand for single-family homes with larger lots

Rising household incomes enabling long-distance commuting

Availability of affordable land at metropolitan edges

Perceived quality-of-life benefits such as quieter neighborhoods and lower congestion

Policy and Planning Factors

Government policies strongly influence sprawl:

Zoning that limits mixed land use

Highway construction that improves long-distance commuting

Mortgage subsidies favoring suburban homeownership

Annexation and local governance practices that encourage outward expansion

Spatial Patterns Caused by Sprawl

Leapfrog Development

Leapfrog development occurs when growth jumps over undeveloped land to create distant, isolated subdivisions.

Leapfrog Development: A pattern in which new development occurs far from existing urbanized areas, leaving intervening land underused.

This creates scattered, discontinuous growth across a metropolitan region.

From the air, suburban sprawl appears as a patchwork of single-family homes, wide roads, and parking lots spreading outward over former farmland or forests.

This aerial photograph of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania shows low-density residential development extending into surrounding green areas, illustrating how suburban sprawl converts open space to built land while maintaining a car-oriented pattern of streets and land use. Source.

Ribbon and Strip Development

Commercial strips along highways—lined with retail stores, parking lots, and signage—form in car-oriented environments. These corridors:

Increase traffic volumes

Reduce aesthetic quality

Reinforce automobile dependence

Edge Expansion

Residential subdivisions often expand outward in contiguous but sprawling patterns, producing miles of low-density neighborhoods.

Urban Planning Responses to Sprawl

While this subsubtopic focuses on sprawl as a sustainability issue, it is important to recognize that urban planners analyze sustainability impacts to guide better land use. Responses outside this subsubtopic—such as smart-growth or mixed-use zoning—are addressed elsewhere in the syllabus, but the need for such responses stems from the sustainability challenges posed by sprawl.

At the metropolitan scale, sprawling development forces residents to drive longer distances for daily activities, increasing vehicle miles traveled and associated emissions.

This aerial photograph shows Phoenix spreading outward as a vast field of low-rise, low-density development connected by highways and arterial roads. It highlights how regional suburban sprawl creates a highly car-dependent urban form and increases the cost of providing infrastructure across such a large area; the desert context provides additional detail beyond the AP syllabus but reinforces the sustainability concerns discussed. Source.

FAQ

Sprawling development forces local governments to extend roads, water lines, sewer systems, and emergency services over large areas. This increases per-resident costs because infrastructure stretches further but serves fewer people.

To cover these expenses, councils may:

Raise property taxes

Increase service fees

Reduce investment in public facilities such as parks or libraries

Over time, low-density areas often generate less revenue than they require in upkeep, creating long-term fiscal pressure.

Suburban expansion often targets flat, easily buildable land, making agricultural fields, grasslands, and wetlands especially vulnerable.

These ecosystems face risk because they:

Require large contiguous areas for species movement

Often lie on metropolitan fringes where development is cheaper

Provide ecosystem services such as flood mitigation, which are lost when paved over

Wetlands are particularly at risk due to drainage for housing and roads.

Public transport systems rely on dense population clusters to support frequent service and justify operating costs.

Sprawling neighbourhoods:

Spread residents across wide areas

Produce low ridership density

Make it costly to run buses or trains without financial loss

As a result, transit routes become indirect, infrequent, or economically unviable, reinforcing car dependence.

Low-density homes often require more energy for heating, cooling, and electricity due to their larger size and detached structure.

Additional factors include:

Increased exposure to outdoor temperatures compared with flats

Greater surface area per dwelling, which loses heat more easily

Higher energy demand from larger gardens, outdoor lighting, and appliances

These patterns compound the energy impacts already driven by car travel.

In dry regions, suburban development increases pressure on limited water supplies because detached homes often have gardens, swimming pools, and high outdoor water use.

Sprawl also expands impermeable surfaces that reduce groundwater recharge. Over time, this combination can:

Lower aquifer levels

Increase reliance on costly water imports

Heighten vulnerability during drought years

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which suburban sprawl increases environmental sustainability challenges for cities.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks for a clear and accurate explanation.

1 mark: Identifies a sustainability challenge linked to suburban sprawl (e.g., increased car dependence, greater land consumption, higher emissions).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation of why suburban sprawl causes this challenge (e.g., low-density development requires longer travel distances).

3 marks: Offers a clear and geographically accurate link to environmental sustainability (e.g., more emissions due to vehicle miles travelled, loss of green space reducing ecosystem services).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of urban geography, analyse how suburban sprawl shapes both the spatial structure and the long-term infrastructure demands of a metropolitan region.

Question 2

Award marks for depth of analysis, accurate use of geographical concepts, and clear links to suburban sprawl.

1–2 marks: Identifies key features of suburban sprawl (e.g., low-density development, separation of land uses).

3–4 marks: Explains how these features shape spatial structure (e.g., outward expansion, fragmented land-use patterns, increased reliance on roads).

5–6 marks: Analyses how these patterns affect long-term infrastructure demands (e.g., need for extended water, sewer, energy, and road networks; higher maintenance costs per resident; challenges in providing efficient public transport).