AP Syllabus focus:

‘Sanitation challenges include safe water, wastewater treatment, and waste management, which are essential for healthy and livable cities.’

Urban sanitation systems determine public health outcomes by shaping access to clean water, managing waste, and reducing disease risks across growing and densely populated urban environments.

Sanitation and Public Health in Urban Areas

Urban sanitation is a foundational component of urban sustainability because effective systems protect residents from contamination, disease, and environmental degradation. As cities grow, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions, the demand for safe drinking water, efficient wastewater treatment, and reliable waste management intensifies. These systems directly influence livability, environmental quality, and the overall functioning of urban spaces.

The Importance of Safe Water Access

Access to safe water underpins healthy urban living and reduces vulnerability to waterborne disease.

Safe Water Access: Reliable availability of water that is free from biological, chemical, and physical contaminants harmful to human health.

Cities face challenges when population growth outpaces infrastructure capacity or when aging systems fail. Pollution from agriculture, industry, or informal settlements can also compromise water sources. Modern cities use layered systems to ensure water safety, including treatment facilities, distribution networks, and monitoring tools.

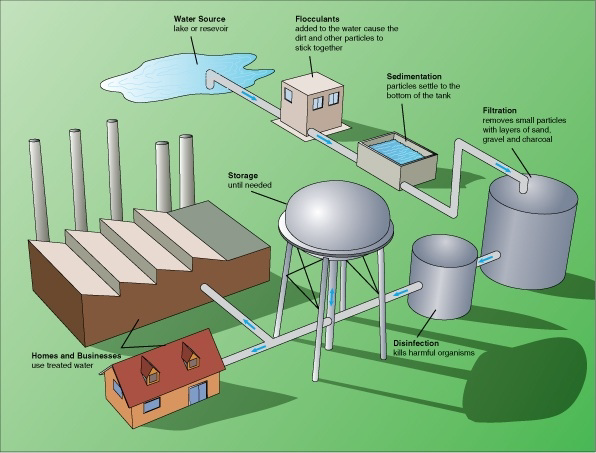

Illustration of a typical drinking water treatment process, showing how raw water passes through coagulation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection before distribution. The diagram helps students visualize how multiple treatment stages remove particles and pathogens to produce safe drinking water. It includes slightly more technical detail than the syllabus requires, but all stages shown are consistent with the core AP Human Geography focus on safe water and public health. Source.

Wastewater Treatment and Urban Health

Wastewater treatment prevents pathogens and pollutants from reentering the environment. Without treatment, wastewater can contaminate drinking water supplies, damage ecosystems, and spread diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery.

Wastewater: Water that has been used in households, industries, or storm runoff and requires treatment before returning to the environment.

Urban wastewater systems typically involve multiple stages of processing.

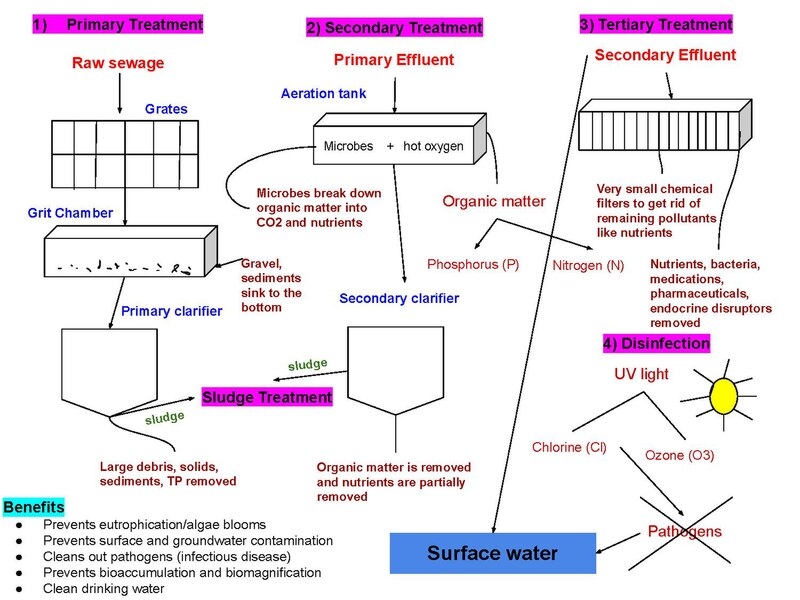

Diagram of a sewage treatment process, showing how raw sewage moves through successive treatment stages before being discharged as treated effluent. The flow arrows and labels help students connect abstract terms like “primary” and “secondary” treatment to a concrete process. The diagram also notes environmental benefits and specific contaminants removed, which goes slightly beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but remains directly related to sanitation and public health. Source.

When infrastructure is inadequate, untreated wastewater may be discharged into local rivers or coastal areas, creating severe public health risks.

Waste Management and Sanitation Challenges

Waste management includes the collection, transport, and processing of solid waste. Effective systems help maintain clean urban environments and prevent disease vectors such as rodents and insects from thriving.

Cities that cannot manage solid waste often experience open dumping, uncontrolled burning, or landfill overcapacity. These practices contribute to health hazards, poor air quality, and environmental degradation.

Why Sanitation Is a Core Urban Sustainability Issue

Sanitation is fundamental to maintaining healthy and livable cities because it reduces exposure to contaminants, supports environmental protection, and ensures that urban development aligns with human well-being. Sanitation challenges are particularly acute in rapidly growing urban areas of the periphery and semiperiphery, where infrastructure investment may lag behind population change.

Key Sanitation Processes in Urban Areas

Urban sanitation systems involve a series of interconnected steps that support public health and environmental protection:

Water sourcing and treatment to ensure potable supplies for households, schools, and workplaces.

Distribution networks that deliver treated water across neighborhoods.

Sewer systems that collect wastewater from residential, industrial, and commercial land uses.

Wastewater treatment plants that remove pollutants and pathogens through primary, secondary, and advanced processes.

Solid waste collection systems, including municipal services and private contractors.

Waste processing, such as recycling, composting, and sanitary landfills.

Environmental monitoring to track contamination risks and ensure regulatory compliance.

Social and Spatial Inequalities in Sanitation Access

Sanitation access is often uneven across a city. Certain neighborhoods—especially low-income areas, informal settlements, and zones of abandonment—experience greater exposure to waste, contaminated water, or unreliable service. This unevenness highlights the links between infrastructure, politics, and power, because decisions about investment and service provision often reflect historical inequalities.

Inadequate sanitation contributes to environmental injustice by concentrating health hazards in particular communities.

A caregiver helps her child use a household latrine in an open-defecation-free village in Papua Province, Indonesia. The image illustrates how access to basic sanitation facilities reduces exposure to human waste and lowers the risk of diarrheal disease. The article includes broader global sanitation information that exceeds the syllabus, but the photo directly reinforces the link between sanitation access and public health. Source.

Poor sanitation also intersects with housing quality, access to healthcare, and exposure to pollution, creating cumulative disadvantages.

Public Health Impacts of Poor Sanitation

When sanitation systems fail, the impacts can be immediate and severe. Public health consequences include:

Waterborne disease outbreaks, particularly following flooding or infrastructure breakdowns.

Increased childhood illness, including diarrhea and parasitic infections.

Exposure to toxic substances from industrial runoff or unsafe waste disposal.

Air quality issues from burning waste or decomposing organic materials.

Food contamination, especially in dense markets where waste management is inadequate.

Cities with rapidly growing populations are especially vulnerable because informal expansion often occurs faster than the extension of sanitation networks.

Urban Governance and Sanitation Infrastructure

Sanitation systems depend on coordinated planning and investment across multiple agencies and jurisdictions. Fragmented governance can result in inconsistent service quality, gaps in coverage, and inefficient resource allocation. Effective sanitation planning requires:

Integrated water and waste policies.

Long-term infrastructure investment.

Cross-jurisdictional coordination.

Enforcement of environmental and public health regulations.

Community engagement, particularly in informal settlements.

Technological and Sustainable Approaches

Advances in sanitation technology can support more resilient urban systems. These approaches include:

Decentralized wastewater treatment, which uses smaller local systems rather than relying solely on large plants.

Low-energy purification technologies, such as ultraviolet disinfection or membrane filtration.

Waste-to-energy systems that convert solid waste or organic matter into usable power.

Green infrastructure, including constructed wetlands that naturally filter wastewater while providing habitat and recreational space.

These strategies align sanitation with urban sustainability goals by reducing environmental impacts and improving overall system resilience.

FAQ

Formal neighbourhoods typically have established water networks, sewer connections, and scheduled waste collection, reducing direct exposure to contaminants.

Informal settlements often lack legal recognition, limiting government investment in sanitation. Residents may rely on shared latrines, informal waste disposal sites, or contaminated water sources.

These differences create unequal health risks, with informal settlements experiencing higher rates of waterborne illness and environmental hazards.

Climate change can overwhelm ageing or undersized sanitation infrastructure. Heavy rainfall and flooding can cause sewage overflows, spreading pathogens into streets, homes, and water supplies.

Prolonged drought reduces safe water availability, forcing some communities to use lower-quality sources.

Rising temperatures accelerate the growth of harmful bacteria in surface water, increasing contamination risks.

Cultural norms can shape whether residents use shared facilities, adopt household latrines, or handle waste in certain ways. In some places, taboos around waste disposal or gender-based restrictions affect access to sanitation facilities.

Community involvement and culturally informed public health campaigns are often crucial for successful sanitation improvements.

Well-designed systems consider privacy, safety, and community preferences to ensure sustained

Sanitation requires coordination between water supply, drainage, housing, transport, and land-use planning.

Integrated planning helps ensure that:

• New housing developments include appropriate infrastructure

• Wastewater networks expand alongside population growth

• Green infrastructure supports stormwater management

Without coordination, sanitation upgrades may be piecemeal, leading to gaps in service coverage and increased public health risks.

Megacities produce enormous volumes of waste daily, placing heavy pressure on collection, transport, and processing systems.

Congested traffic, limited landfill space, and sprawling informal settlements complicate efficient waste collection.

Informal waste pickers often play an essential role in recycling but may lack protective equipment, increasing health risks. Effective management must balance efficiency, environmental sustainability, and worker safety.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain how inadequate wastewater treatment can affect public health in rapidly growing cities.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a specific public health impact (e.g., spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, or diarrhoeal illness).

• 1 mark for explaining the mechanism (e.g., untreated wastewater contaminates drinking water sources or local waterways, increasing exposure to pathogens).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Assess how inequalities in access to sanitation services can contribute to environmental injustice within urban areas.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for defining or describing environmental injustice (e.g., unequal exposure to environmental hazards among different social groups).

• 1 mark for identifying a group or area typically affected (e.g., low-income neighbourhoods, informal settlements, zones of abandonment).

• 1 mark for explaining how limited access to safe water or sanitation facilities increases exposure to risks (e.g., contamination, waste accumulation, higher disease prevalence).

• 1 mark for linking sanitation infrastructure decisions to political, economic or spatial inequality (e.g., underinvestment in marginalised neighbourhoods).

• 1 mark for providing a clear assessment point, such as recognising that uneven sanitation access reinforces broader social and health disparities.