AP Syllabus focus:

‘Cities often have large ecological footprints and high energy use because of concentrated consumption, transportation needs, and built infrastructure.’

Urban areas consume vast resources and energy, creating significant environmental pressures. Understanding ecological footprints and energy use reveals how urbanization drives sustainability challenges in rapidly growing global cities.

Ecological Footprint and Urban Consumption

Urban areas generate disproportionately large ecological footprints, a term referring to the total amount of land, water, and resources required to support a population’s consumption and absorb its waste. This metric highlights how concentrated populations place heavy demands on global ecological systems through resource use, infrastructure needs, and waste production.

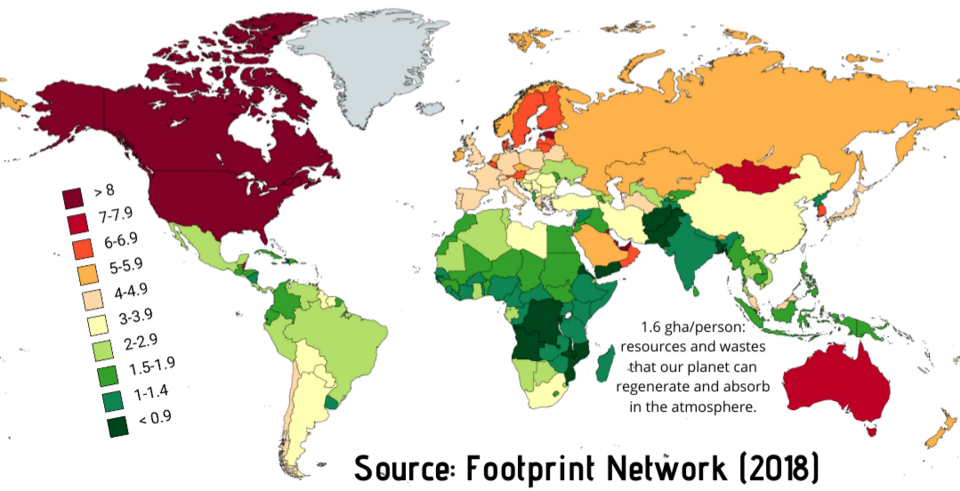

World map showing countries classified by ecological footprint per person in 2018. Darker shades represent higher per-capita resource demand, illustrating where consumption and waste generation place heavy pressure on ecosystems. The map provides national context that helps explain how urban ecological footprints contribute to broader environmental patterns. Source.

Ecological Footprint: The measure of the biologically productive land and water required to supply resources and absorb waste for a population.

One normal sentence to follow the definition and meet formatting rules.

Cities intensify resource consumption because they cluster residents and economic activity. Although density can reduce per-capita resource use, overall demand for food, manufactured goods, construction materials, and services makes urban footprints large. Key drivers include:

High consumption rates linked to rising urban incomes

Built infrastructure that requires energy-intensive construction and maintenance

Food and goods provision systems that depend on long-distance supply chains

Waste generation that often exceeds local environmental capacity

Energy Use in Urban Environments

Energy use forms a central component of the urban ecological footprint, reflecting how cities rely on electricity, heating, cooling, and transportation systems to function. Urban areas account for the majority of global energy consumption due to high densities of homes, commercial buildings, industries, and commuters.

Global composite image of Earth’s city lights at night, showing bright clusters of electricity use in dense urban regions. The illuminated patterns highlight where energy demand is concentrated along coasts, transportation corridors, and large metropolitan areas. The map offers global context for understanding the spatial distribution of urban energy consumption. Source.

Energy Use: The total amount of power consumed to support activities such as transportation, heating, cooling, lighting, and industrial processes.

One normal sentence to meet separation rules.

Urban energy demand is shaped by several structural and socioeconomic factors:

Transportation systems, especially those dependent on private automobiles

Building characteristics, including age, insulation quality, and heating/cooling technology

Industrial and commercial activity, which can be energy intensive

Urban form, such as low-density sprawl that increases travel distances

Energy Use and Urban Form

Urban form—the spatial layout and design of a city—strongly influences both energy consumption and ecological footprint size. Low-density, car-oriented metropolitan regions generally consume more energy per person than compact, transit-oriented cities.

Low-Density Urban Form

Low-density development creates patterns that increase residents’ reliance on automobiles and expand the area needed for housing and infrastructure. These features often raise the ecological footprint because:

Roads, parking lots, and utilities must stretch over larger areas

Private-vehicle use requires extensive fuel consumption

Single-family homes typically need more energy for heating and cooling

Dispersed land use increases the distance goods must travel to reach consumers

High-Density Urban Form

High-density environments can reduce total energy use by placing homes, businesses, and services closer together. While density requires significant initial energy investment in construction, it can lower long-term consumption by:

Supporting public transportation systems with higher ridership

Allowing shorter walking and cycling distances

Encouraging mixed-use development that limits commuting

Improving efficiency in heating and cooling multi-unit buildings

Transportation, Energy, and the Urban Ecological Footprint

Transportation systems form one of the largest contributors to urban energy use. Cities that rely heavily on automobiles experience higher fossil fuel consumption, greater emissions, and increased land devoted to road networks.

Photograph of severe traffic congestion in Delhi, illustrating how car-dependent transport systems increase fuel use, emissions, and roadway land demand. The dense mix of vehicles reflects the high-energy mobility patterns common in large metropolitan regions. While the image does not show energy data directly, it provides a clear real-world example of transport-driven urban energy consumption. Source.

In contrast, cities that invest in rail transit, bus rapid transit, and active transportation infrastructure can significantly reduce their ecological footprint.

Key transportation-related factors shaping energy use include:

Mode choice, particularly the availability of reliable transit alternatives

Commuting distances, which reflect urban design and job-housing patterns

Traffic congestion, leading to energy waste through idling and slow speeds

Fuel type, with electric and hybrid vehicles offering potential reductions in emissions

Built Infrastructure and Energy Demand

Infrastructure embedded within cities—such as water systems, lighting, heating networks, and communication technologies—requires steady energy input. The ecological footprint of built infrastructure grows as systems expand to accommodate population growth and economic development.

Urban infrastructure contributes to high energy use in several ways:

Water pumping and treatment, which demand continuous electricity

Street lighting and public facilities that operate throughout the day

Manufacturing zones, which rely on steady industrial energy supplies

Construction of new districts, where material production and transportation are energy intensive

Strategies to Reduce Urban Ecological Footprints and Energy Use

Efforts to shrink urban ecological footprints focus on increasing efficiency, shifting energy sources, and redesigning urban spaces to reduce demand. Common strategies include:

Expanding renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal systems

Improving building efficiency through insulation, energy-efficient appliances, and smart systems

Redesigning transportation networks to prioritize transit, biking, and walking

Encouraging compact, mixed-use development, which reduces the need for long trips

Adopting circular-economy principles, such as recycling, local sourcing, and waste-to-energy projects

These approaches aim to lower total consumption while supporting sustainable growth, aligning with the syllabus emphasis on how cities’ large ecological footprints and high energy use influence environmental quality and long-term urban resilience.

FAQ

An ecological footprint measures how much land and water a population requires to supply resources and absorb waste. A carbon footprint focuses specifically on greenhouse gas emissions.

The two footprints overlap, but cities can have a relatively small carbon footprint yet a large ecological footprint if they import large quantities of food, materials, and manufactured goods.

Higher incomes often lead to increased consumption of goods, services, and energy-intensive products.

Efficient infrastructure may reduce per-capita energy use, but overall demand for resources expands through:

Larger housing sizes

Increased travel and leisure consumption

Higher rates of electronic and material turnover

Thus, efficiency does not always offset lifestyle-related resource use.

Urban heat islands raise local temperatures, increasing the need for cooling in homes, offices, and public buildings.

This intensifies electricity consumption, particularly during peak summer periods, and raises the ecological footprint through additional energy generation, often reliant on fossil fuels.

Vegetation loss, heat-absorbing surfaces, and dense built environments all contribute to this effect.

Food transported from distant regions significantly increases a city’s ecological footprint.

Urban populations rely heavily on external agricultural land, leading to resource use beyond city boundaries. Key contributors include:

Long supply chains

Refrigeration and storage needs

High consumption of meat and processed foods

Local food production and shorter supply chains can reduce these impacts.

Many older cities have ageing buildings with poor insulation, outdated heating systems, and inefficient energy infrastructure.

Even though they are spatially compact, their built environments may require substantially more energy for heating, cooling, and maintenance. Retrofitting older structures is costly and slow, limiting rapid improvements in energy efficiency.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which urban form can influence a city's ecological footprint.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant aspect of urban form (e.g., low-density development, compact/high-density design, transport layout, mixed land use).

1 mark for explaining how that aspect affects resource consumption, land use, or travel behaviour.

1 mark for linking the explanation directly to ecological footprint (e.g., greater land demand, higher fuel use, increased infrastructure requirements).

Example of a 3-mark answer:

Identifies low-density sprawl (1 mark).

Explains that it increases reliance on cars and extends infrastructure across a larger area (1 mark).

Links this to a larger ecological footprint due to higher fuel use and more land consumption (1 mark).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of ecological footprints and urban energy use, evaluate how two different urban strategies can reduce the environmental impact of rapidly growing cities.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for accurately identifying each strategy (e.g., public transport expansion, compact development, renewable energy adoption, building efficiency standards).

1–2 marks for explaining how each strategy reduces energy use or resource demand.

1–2 marks for evaluative points about the effectiveness or limitations of each strategy (e.g., cost, implementation challenges, unequal access, long-term sustainability impacts).

Examples of acceptable evaluative points:

Public transport reduces per-capita emissions but requires significant investment and may not reach peripheral populations.

Compact development lowers travel demand but can raise housing prices or reduce green space.