AP Syllabus focus:

‘Urban sustainability challenges arise when rapid growth strains resources, increases pollution, and raises the ecological footprint of cities.’

Urban sustainability challenges emerge as fast-growing cities struggle to balance development with environmental limits, resource needs, public health, and long-term resilience across diverse urban systems.

Understanding Urban Sustainability Challenges

Urban sustainability challenges refer to the pressures created when urban growth outpaces a city’s capacity to manage environmental, social, and infrastructural demands. These challenges connect directly to how cities consume resources, generate waste, and shape human well-being. A sustainable city must maintain livability while protecting ecological systems, yet rapid expansion often makes this balance difficult.

Key Concepts in Urban Sustainability

Urban areas tend to concentrate population, industry, and infrastructure. As a result, they magnify both human impacts and opportunities for innovation. Sustainability issues emerge when these impacts exceed the capacity of natural systems or urban infrastructure to absorb, mitigate, or manage them.

Urban Sustainability Challenges: Pressures that arise when a city’s growth exceeds its ability to provide resources, manage pollution, and maintain environmental and social stability.

Urban challenges frequently intersect, meaning one problem can worsen another. For example, insufficient public transit increases car dependence, which contributes to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, influencing urban heat and environmental health.

Drivers of Urban Sustainability Challenges

Rapid Urbanization and Resource Demand

Rapidly expanding cities face increasing demands for water, energy, food, and land. As populations grow, the rate of consumption accelerates, placing stress on finite resources.

Key pressure points include:

Rising freshwater demand for households, industry, and agriculture

Increasing energy consumption as built environments expand

Greater land conversion for housing and infrastructure

Higher waste generation and solid-waste disposal needs

Because resources are unevenly distributed globally, some regions encounter sharper sustainability pressures than others. Cities in the periphery and semiperiphery frequently face accelerated growth without equivalent infrastructure investment.

Pollution and Environmental Degradation

Pollution forms a central component of urban sustainability challenges. Cities produce concentrated emissions and waste, affecting air quality, water systems, and soil health.

Common contributors include:

Vehicle emissions that heighten particulate matter and smog

Industrial runoff contaminating waterways

Heat islands created by dense built environments

Overflowing landfills and improper waste disposal

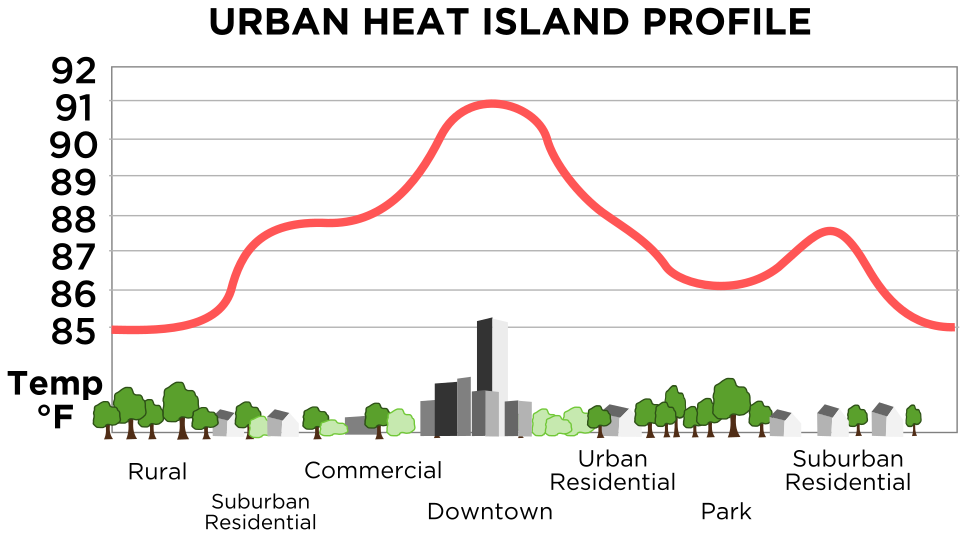

Urban Heat Island: A localized increase in temperature in urban areas caused by extensive built surfaces that absorb and retain heat.

Pollution threatens ecosystems, increases respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses, and reduces the quality of life.

This diagram shows how temperatures rise from rural to urban cores, illustrating the urban heat island effect. The red curve visualizes how built environments retain more heat. Some specific place labels and values exceed syllabus requirements but reinforce the central concept. Source.

It also reinforces socio-spatial inequalities since marginalized populations often reside in more polluted neighborhoods.

Ecological Footprint and Exceeding Environmental Limits

Measuring Urban Impact on the Environment

Cities often have large ecological footprints, meaning they require far more land and resources than their physical boundaries contain.

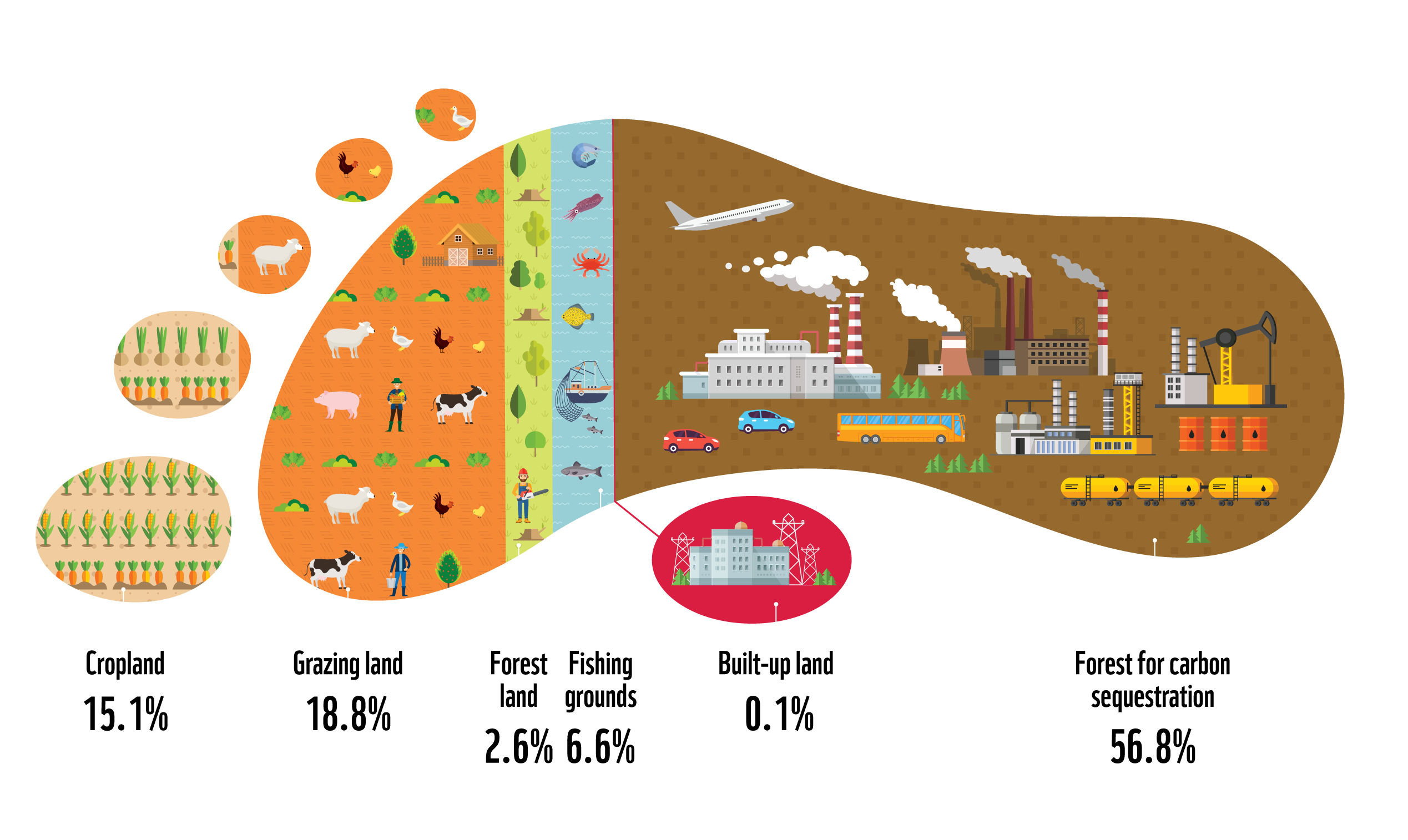

This infographic demonstrates how urban consumption can require multiple Earths’ worth of resources, highlighting the severity of ecological overshoot. It visually links city lifestyles to the land and sea area needed to sustain them. Some Hong Kong–specific statistics exceed syllabus focus but strengthen conceptual understanding. Source.

This reflects the energy used to support transportation networks, building operations, food systems, and consumer goods.

Ecological Footprint: A measure of the land and resources required to support a population’s consumption and absorb its waste.

Because dense populations rely on extended supply chains, the ecological consequences of urban consumption often occur outside city borders. These impacts can include deforestation, water diversion, agricultural stress, and global carbon emissions.

A city’s ecological footprint grows when:

Transportation systems rely heavily on fossil fuels

Buildings have high energy demands

Waste volumes exceed treatment capacity

Consumption patterns intensify with rising incomes

Infrastructure Stress and Systemic Vulnerabilities

Aging or Inadequate Infrastructure

Urban sustainability challenges become severe when infrastructure cannot keep pace with population growth. Without adequate systems, cities struggle to deliver safe water, sanitation, energy, and mobility.

Pressures emerge in areas such as:

Water supply networks strained by demand and drought

Sanitation systems overwhelmed by waste and wastewater

Energy grids that cannot meet peak consumption

Transportation systems clogged by congestion and limited transit

Breakdowns in these systems ripple across daily life, reducing productivity, limiting mobility, and increasing public health risks.

Climate Change as an Amplifier

Climate change intensifies sustainability challenges by increasing heat, flooding, storms, and sea-level rise.

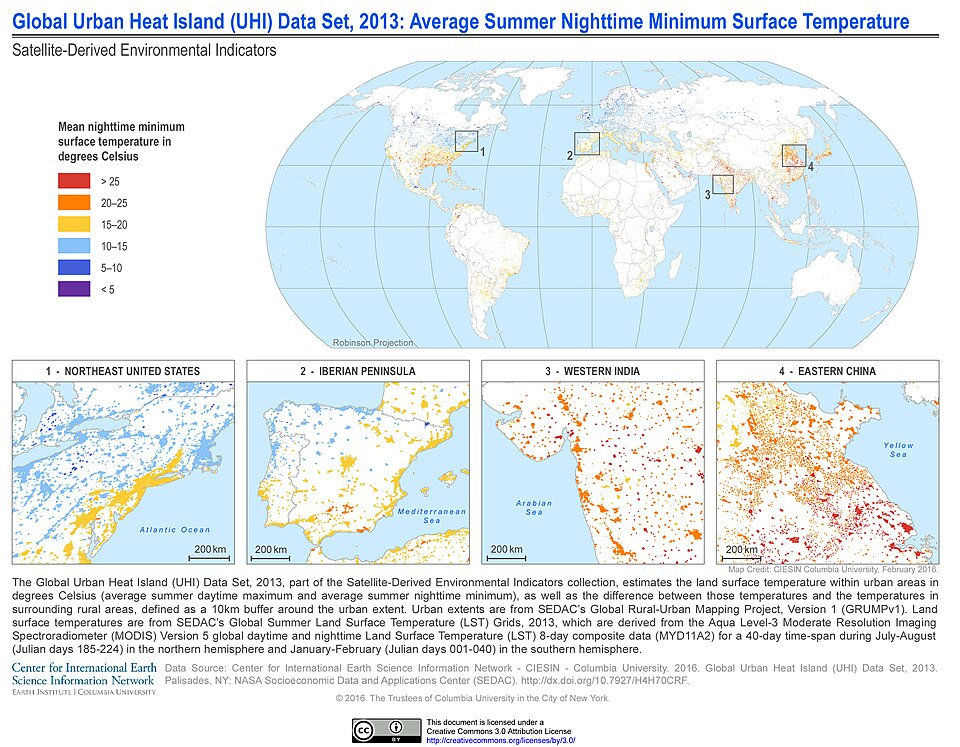

This global map illustrates where urban heat island effects are strongest, revealing spatial patterns of temperature differences between cities and surrounding areas. It highlights regional vulnerability to climate-related heat stress. The full legend and dataset details extend beyond the syllabus but deepen conceptual understanding. Source.

These impacts add stress to already strained systems and create new vulnerabilities.

Cities experience:

Stronger heat waves affecting health and energy demand

Flooding that damages housing, utilities, and transportation

Storm surges threatening coastal infrastructure

Shifts in water availability that limit supply

Urban planning must anticipate these risks to protect populations and maintain functioning systems.

Social Dimensions of Urban Sustainability

Inequities in Exposure and Access

Urban sustainability challenges are not experienced equally. Social groups differ in their exposure to pollution, risk, and inadequate services.

Examples of unequal impacts include:

Low-income neighborhoods near industrial zones

Limited access to clean water or reliable transit

Higher vulnerability to climate-related hazards

Reduced political representation in planning processes

Inequality restricts overall urban resilience by reducing the ability of populations to adapt to environmental stressors.

Governance and Policy Barriers

Effective sustainability planning requires coordination, investment, and regulation. However, fragmented governance and inconsistent policy enforcement can obstruct long-term solutions. Competing political interests, limited budgets, and uneven implementation frequently weaken sustainability initiatives.

Interconnected Nature of Urban Sustainability Challenges

Urban sustainability challenges do not occur in isolation. Resource scarcity, pollution, ecological strain, infrastructure stress, and social inequities reinforce one another, shaping a complex set of issues cities must navigate as they grow.

FAQ

Geographers look for measurable signs that urban systems are under stress, such as declining air or water quality, rising energy consumption, increasing waste volumes or worsening inequality in access to services.

They also assess whether infrastructure is struggling to keep up with population growth, for example through more frequent power outages, water shortages or extended travel times due to congestion.

Long-term trends, rather than isolated events, are key to determining the severity of sustainability pressures.

Land-use choices determine how far people must travel, the density of development and the proportion of green space, all of which shape environmental impacts.

For example:

• Low-density, sprawling development typically increases car dependence and energy use.

• High-density areas reduce land consumption but may intensify heat retention.

• Green spaces help absorb pollutants, regulate temperature and mitigate stormwater runoff.

Different cities have varying industrial profiles, transportation systems and regulatory frameworks, which influence pollution levels.

Cities heavily reliant on private vehicles or fossil-fuel-based industry tend to generate faster pollution growth. By contrast, places with strong environmental regulation or efficient public transit may limit pollution despite similar population trends.

Local geography, such as basins that trap smog, can also exacerbate pollution levels.

Rapid urban growth leaves little time for planning, investment or adaptation, making challenges more difficult to manage.

Slow or moderate growth allows governments to:

• Expand infrastructure at a manageable pace

• Design long-term resource strategies

• Implement gradual policy changes

• Coordinate land-use planning with environmental goals

When growth is rapid, informal settlements and insufficient infrastructure often develop faster than governments can respond.

Technology can reduce pressures by improving efficiency, monitoring environmental change and supporting sustainable infrastructure.

Examples include:

• Smart grids that balance electricity demand

• Sensors that track air quality and guide interventions

• Water recycling systems that reduce freshwater use

• Building materials designed to lower heat retention

However, technological solutions require investment and may widen inequalities if only accessible to certain neighbourhoods.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which rapid urban population growth can create an urban sustainability challenge.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant sustainability challenge (e.g., pressure on water supply, increased pollution, rising energy demand, waste accumulation).

• 1 mark for describing how rapid population growth leads to this challenge (e.g., more residents increasing demand for limited resources).

• 1 mark for outlining a consequence for the city (e.g., reduced air quality, infrastructure strain, environmental degradation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how climate change can intensify existing urban sustainability challenges in rapidly growing cities.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying at least one existing sustainability challenge (e.g., heat stress, inadequate infrastructure, pollution).

• 1 mark for explaining how climate change interacts with or worsens this challenge (e.g., heatwaves amplifying heat island effects).

• 1 mark for describing environmental or social outcomes (e.g., increased health risks, higher energy use, damage to infrastructure).

• 1 mark for linking climate impacts to resource or infrastructure pressures (e.g., storms overwhelming drainage systems).

• 1 mark for discussing variation or uneven vulnerability within the city (e.g., low-income neighbourhoods facing greater risk).

• 1 mark for providing an overall assessment or judgement about the significance of climate change as an intensifying factor.