AP Syllabus focus:

‘Infrastructure decisions reflect local politics and power by shaping which neighborhoods receive investment, services, and connectivity.’

Infrastructure reflects political choices that determine which urban areas gain or lose access to essential services, influencing spatial equity, economic opportunities, and everyday urban life.

Infrastructure, Politics, and Uneven Urban Development

Infrastructure in cities is never neutral; it is deeply shaped by political interests, governance structures, and power dynamics. Because infrastructure—the systems that support transportation, water, sanitation, energy, and communication—underpins nearly all urban functions, decisions about where it is placed or improved directly influence urban spatial patterns. Infrastructure investment can reinforce existing inequalities or attempt to alleviate them, depending on political priorities and public accountability. Local governments, private developers, and regional authorities often compete over limited resources, leading to uneven outcomes in access and service quality.

How Political Power Shapes Infrastructure Allocation

Decision-Making Structures

Political institutions play a central role in determining how infrastructure is distributed across a metropolitan area. Elected officials, planning agencies, and public–private partnerships evaluate proposals, manage funding, and select projects. However, these processes often reflect broader power relations between neighborhoods, interest groups, and economic elites.

Key factors influencing political allocation of infrastructure include:

Electoral incentives, where politicians prioritize improvements in areas with strong voter support.

Lobbying by influential developers seeking infrastructure that enhances land values.

Historic patterns of disinvestment, which may persist due to political neglect or discriminatory planning.

Budget constraints, pushing governments to prioritize high-return or highly visible projects.

Because political influence varies widely across neighborhoods, infrastructure allocation can intensify social inequalities by improving already-advantaged districts while leaving marginalized communities behind.

Infrastructure as a Tool of Political Control

Infrastructure also functions as a mechanism through which governments exercise control over urban space. Certain projects may be deployed to stimulate growth, attract investment, or reshape neighborhood demographics. Conversely, withholding investment can effectively limit development or maintain socioeconomic boundaries.

Examples of political use of infrastructure include:

Upgrading transit lines to support redevelopment initiatives.

Directing broadband expansion toward business districts rather than low-income communities.

Delaying water-system repairs in politically marginalized neighborhoods.

Channeling highway construction through areas lacking political power, often displacing residents.

Such decisions illustrate how infrastructure becomes intertwined with power, shaping who benefits from urban modernization and who bears its costs.

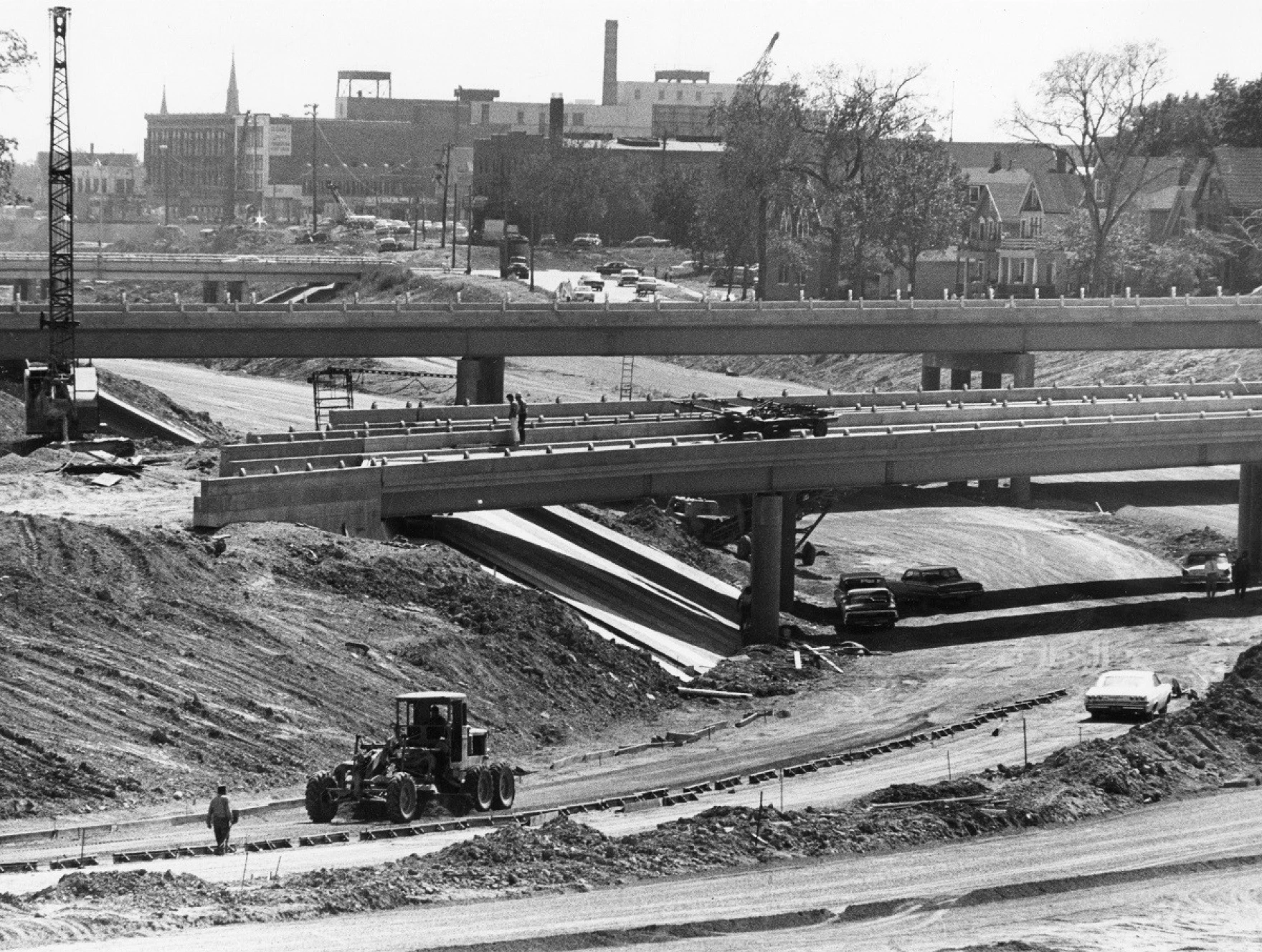

Black-and-white image showing Milwaukee freeway construction in the 1960s, illustrating how large infrastructure projects displaced established neighborhoods. It demonstrates how transportation investments often reshaped urban connectivity and imposed uneven burdens. The Milwaukee case goes beyond AP requirements but clearly visualizes politically driven infrastructure impacts. Source.

Infrastructure, Accessibility, and Spatial Justice

Accessibility as a Political Outcome

Infrastructure determines access to jobs, schools, health care, and transportation, making accessibility a central measure of spatial justice. Accessibility refers to the ease with which people can reach desired locations using available transportation or communication networks.

Accessibility: The ability of people to reach goods, services, and activities efficiently using existing urban infrastructure.

A sentence separating definition block from next content:

Consequently, accessibility patterns reveal broader political priorities and societal divisions.

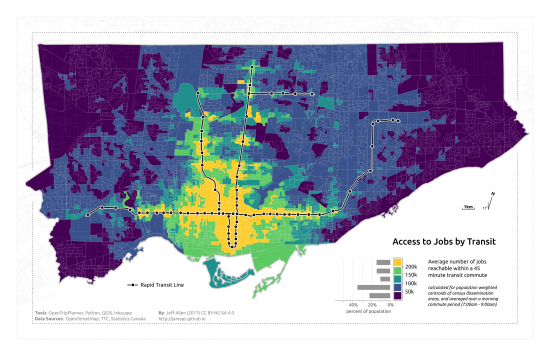

Map showing how access to employment within a 45-minute transit commute varies across Toronto, highlighting neighborhoods with high and low mobility. Areas close to rapid transit corridors show far greater accessibility. Although Toronto-specific, it clearly visualizes how infrastructure allocation produces uneven spatial outcomes. Source.

Uneven Access to Essential Services

Political decisions related to infrastructure can determine which parts of a city receive adequate:

Public transit, affecting commute times and employment opportunities.

Water and sanitation services, essential for public health.

Energy and broadband, shaping digital connections and business development.

Parks and public amenities, influencing environmental quality and neighborhood livability.

When services are unevenly distributed, residents in underserved neighborhoods experience higher costs, reduced mobility, and greater exposure to health risks.

Infrastructure, Investment, and Urban Power Relations

Public vs. Private Influence

The balance of power between public authorities and private actors significantly affects infrastructure planning. Private firms may influence decisions through:

Funding or co-funding projects.

Offering technical expertise.

Aligning infrastructure expansion with corporate interests.

Public sector agencies, meanwhile, must negotiate these pressures while attempting to meet community needs. Conflicts often arise when private priorities diverge from public goals, resulting in infrastructure that benefits specific economic interests rather than the broader population.

Infrastructure as a Driver of Urban Restructuring

New infrastructure can reshape the internal geography of metropolitan areas. Investment in transit corridors, utilities, or communication networks can raise land values, attract new development, and trigger demographic shifts. This process may:

Encourage gentrification by attracting high-income residents.

Displace lower-income communities unable to absorb rising costs.

Reinforce central business district connections while neglecting peripheries.

Change political influence as populations shift across districts.

Some communities gain political visibility through such restructuring, while others lose representation and bargaining power.

Governance Fragmentation and Infrastructure Inequities

Fragmented governance occurs when multiple municipalities, agencies, or districts make infrastructure decisions independently. This fragmentation leads to:

Inconsistent service levels across jurisdictions.

Competition for investment rather than coordinated planning.

Inefficiencies in transportation and utility networks.

Greater inequalities, as wealthier suburbs may invest heavily while poorer areas struggle.

When governance is fragmented, political power becomes unevenly distributed across the metropolitan landscape, amplifying disparities in infrastructure provision and maintenance.

Political Priorities, Funding, and Long-Term Implications

Infrastructure decisions depend on funding from taxes, bonds, and federal or state programs. Political leaders choose which projects receive investment, often favoring those with:

High visibility, such as major transit hubs.

Strong economic returns, such as business district upgrades.

Influence from powerful interest groups.

By contrast, less politically influential neighborhoods may endure aging systems, unreliable services, and limited investment. Over time, these choices reinforce structural inequalities and shape the urban landscape for decades.

FAQ

Political ideologies shape priorities for public spending, determining whether governments emphasise social welfare, market-led growth, or environmental protection.

Left-leaning governments may prioritise infrastructure in underserved neighbourhoods to address inequality, while right-leaning administrations may emphasise business-oriented projects that support economic expansion.

Policies on taxation, privatisation, and public investment also influence which areas receive funding, affecting long-term patterns of accessibility and opportunity.

Chronic underinvestment can persist because of delays in funding, political turnover, or shifting priorities between election cycles.

Local opposition, land ownership disputes, and limited administrative capacity may slow the delivery of promised projects.

In some cases, private companies are reluctant to invest in areas with low profitability, especially for broadband, energy, or transport upgrades.

Advocacy groups can influence planning decisions by organising public consultations, lobbying elected officials, or using legal challenges.

They may demand changes to proposed projects, such as rerouting highways or adding pedestrian infrastructure, ensuring neighbourhood concerns are considered.

Groups with greater resources, networks, or political visibility tend to have stronger influence, which can reinforce unequal outcomes across the city.

Planners typically combine demographic, economic, and spatial data to identify infrastructure needs.

They may evaluate:

Travel times and accessibility gaps

Utility network capacity

Projected population growth

Environmental risk and resilience indicators

Political considerations can override data-led planning, particularly when influential groups pressure decision-makers to prioritise their areas.

Infrastructure can shift political influence by attracting new populations, altering voting patterns, or encouraging economic development.

Neighbourhoods benefiting from improved transport or services may gain higher property values, increased investment, and stronger political representation.

Meanwhile, communities left with deteriorating infrastructure may lose population, reducing their influence in future policy decisions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which political power can influence the distribution of urban infrastructure.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a basic influence of political power (e.g., politicians prioritising areas that support them).

1 additional mark for describing how this affects infrastructure allocation (e.g., improvements directed to politically influential neighbourhoods).

1 additional mark for explaining the outcome or implication (e.g., unequal service provision or reinforced spatial inequality).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using an urban example you have studied, analyse how infrastructure decisions can reinforce social or spatial inequalities within a city.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant urban example (e.g., a named city).

1 mark for describing an infrastructure decision (e.g., location of transport lines, broadband expansion, or highway construction).

1 mark for linking the decision to political or power dynamics (e.g., favouring certain interest groups or neglecting marginalised communities).

1–2 marks for analysing how the decision reinforces social or spatial inequalities (e.g., reduced accessibility, displacement, or uneven economic opportunities).

1 mark for a clear concluding analytical point connecting the infrastructure decision to broader patterns of inequality.