AP Syllabus focus:

‘Infrastructure affects the environment through land consumption, pollution, and resilience to hazards, influencing sustainability and quality of life.’

Urban infrastructure shapes how cities grow and function, and its environmental impacts influence sustainability, exposure to hazards, and the long-term quality of urban life for residents.

Infrastructure and Environmental Land Use Impacts

Infrastructure—particularly transportation networks, energy systems, water supply, and waste services—directly transforms the physical landscape. These systems require land, materials, and ongoing maintenance, and therefore carry environmental consequences that vary by form, density, and spatial pattern.

Land Consumption and Habitat Change

Infrastructure often expands outward as cities grow, consuming open space and altering natural systems.

Construction of highways, rail lines, and airport facilities removes vegetation and reduces habitat connectivity.

Urban expansion supported by new pipes, power lines, and roads can encourage low-density development that spreads across agricultural or undeveloped land.

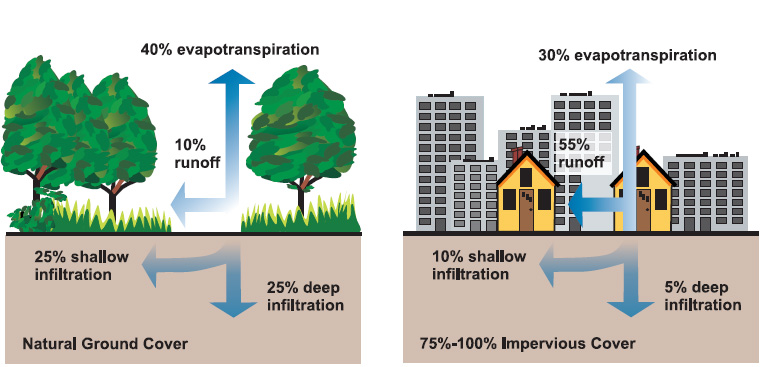

Increased impervious surfaces—pavement, rooftops, and parking areas—reduce soil permeability, disrupt groundwater recharge, and intensify runoff.

This diagram contrasts natural and urbanized landscapes by showing how runoff increases and infiltration declines as impervious surface area expands. It reinforces how infrastructure reshapes hydrology and contributes to environmental change. The percentages shown exceed AP requirements but help illustrate the magnitude of these shifts. Source.

Impervious surface: A land cover such as asphalt or concrete that prevents water from infiltrating the soil, increasing runoff and flood risk.

Even when infrastructure is intended to support growth, its placement often determines how quickly land consumption intensifies. Cities that centralize new infrastructure within already built-up areas can moderate spatial expansion.

Pollution Linked to Infrastructure Systems

Infrastructure contributes to various forms of pollution because it concentrates energy use, transportation flows, and waste production.

Transportation infrastructure is a major source of air pollution, including particulate matter and greenhouse gases from vehicles.

Water systems can generate polluted runoff, especially when storm drains carry oil, debris, and chemicals into rivers or coastal environments.

Energy infrastructure, such as power plants and transmission lines, may emit pollutants depending on the fuel source, affecting regional air quality.

Waste management infrastructure, including landfills and incinerators, can release methane, toxins, and odors, disproportionately affecting nearby communities.

Greenhouse gases: Atmospheric gases such as carbon dioxide and methane that trap heat and contribute to climate change.

Pollution levels often concentrate along transportation corridors, industrial zones, and older infrastructure networks, shaping environmental conditions across neighborhoods.

Infrastructure and Hazard Resilience

Modern cities must manage increasing environmental hazards, and infrastructure plays a key role in determining resilience.

Vulnerability and Risk Exposure

Urban systems rely on interconnected infrastructure networks; when one fails, cascading impacts can occur.

Power outages can disrupt water pumps, transit systems, and communications.

Stormwater systems overwhelmed by extreme rainfall can cause flooding, property damage, and contamination.

Aging infrastructure—bridges, pipes, levees—may increase vulnerability during storms, earthquakes, or heat waves.

Resilience: A city’s ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from environmental hazards.

Resilience varies widely between neighborhoods depending on investment patterns, maintenance cycles, and political priorities.

Infrastructure for Hazard Mitigation

Many cities invest in protective systems that reduce exposure to natural hazards and climate impacts.

Flood control systems, such as levees, wetlands restoration, and stormwater retention basins, reduce flood risk.

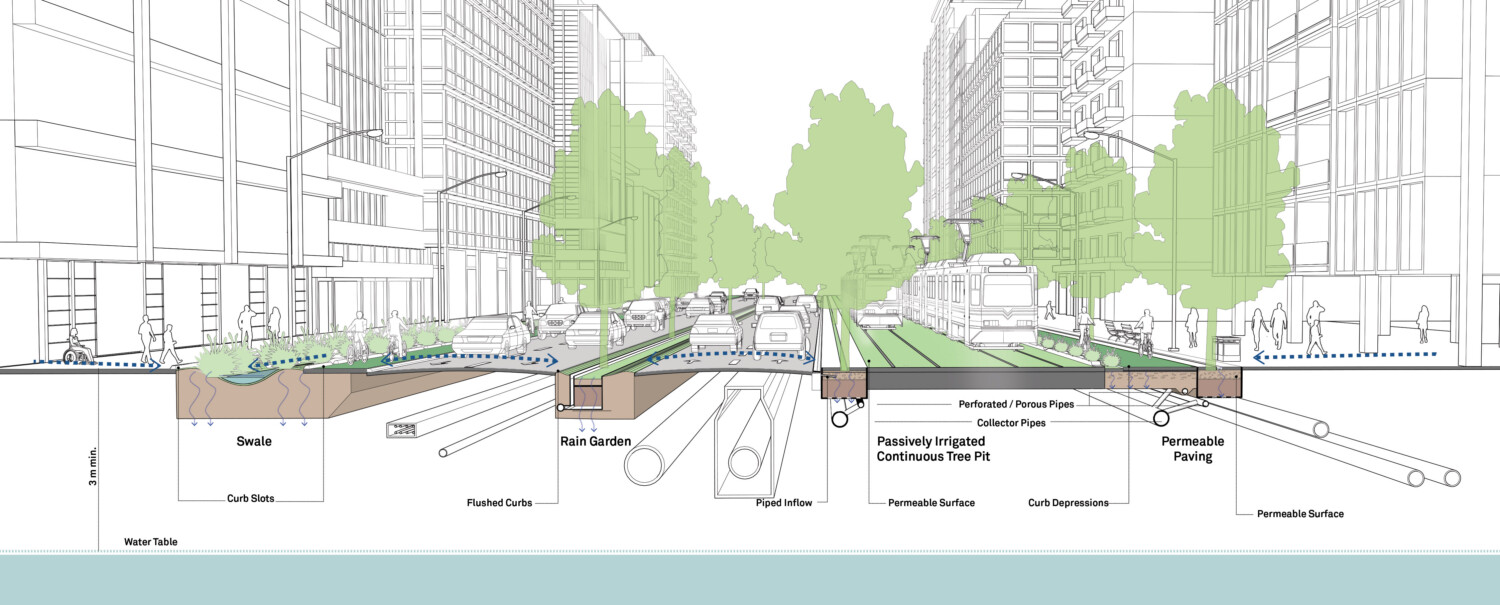

Green infrastructure, including permeable pavements and bioswales, helps absorb runoff and mitigate urban heat.

This cross-section illustrates how stormwater is captured and filtered through swales, rain gardens, permeable surfaces, and tree pits before entering underground pipes. It shows how infrastructure design can reduce runoff and strengthen hazard resilience. The additional underground labeling goes beyond AP scope but enhances understanding of system function. Source.

Emergency transportation and communication systems support evacuation and disaster response.

Reinforced energy grids and microgrids can maintain power during extreme weather events.

These systems not only limit physical damage but also shape long-term sustainability and social stability.

Sustainability and Quality of Life

Environmental impacts of infrastructure influence daily life, access to resources, and overall urban livability.

Energy Use and Urban Resource Demands

Infrastructure determines how efficiently cities consume energy, water, and materials.

Transportation networks that prioritize highways over transit increase car dependence and raise per-capita emissions. In contrast, transit-oriented systems reduce fuel use, pollution, and road congestion. Water and sanitation systems that leak or rely on outdated treatment processes waste resources and weaken environmental health. Efficient infrastructure lowers urban ecological footprints and supports sustainable growth.

Environmental Equity and Community Impacts

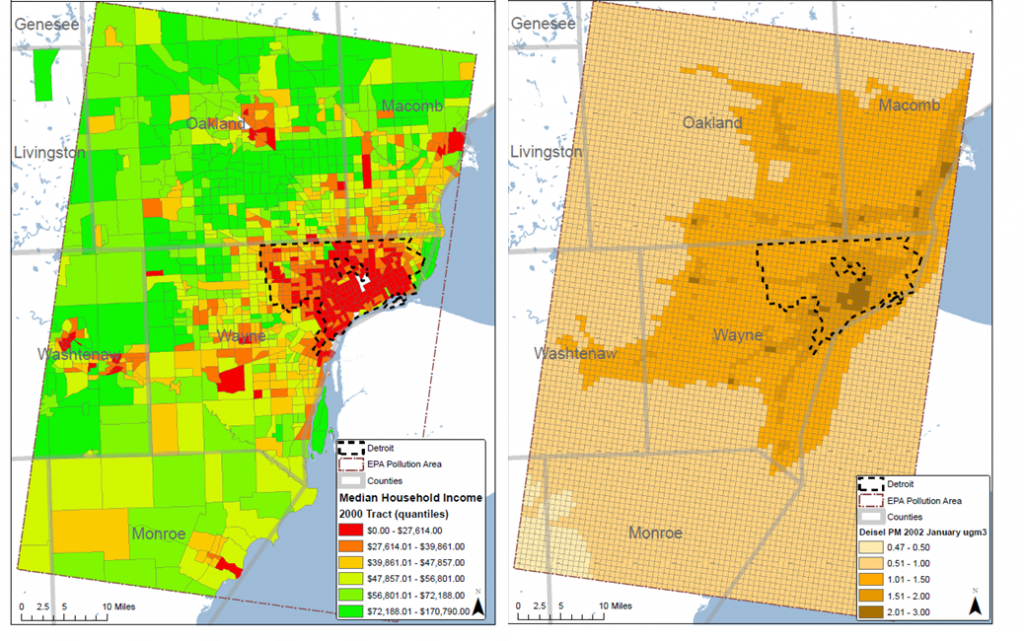

Environmental outcomes linked to infrastructure are rarely distributed evenly.

Low-income and minority neighborhoods often host polluting facilities, major roadways, or older infrastructure vulnerable to breakdown.

These maps reveal how diesel particulate pollution overlaps with lower-income neighborhoods in Detroit, demonstrating unequal environmental burdens. They visually connect infrastructure, emissions, and social inequality. The detailed legends extend beyond AP expectations but clarify how environmental justice is measured. Source.

Wealthier districts may receive more frequent upgrades, cleaner energy options, and protected green spaces.

Unequal distribution of parks, transit, and waste services shapes both environmental quality and health outcomes.

Environmental injustice: Unequal exposure to environmental harms or unequal access to environmental benefits among different social groups.

Infrastructure investment decisions can either reinforce or reduce these inequalities. When planned carefully, infrastructure can improve air quality, reduce hazard risk, and expand quality of life for urban residents. When poorly planned, it can degrade environments, deepen disparities, and weaken long-term sustainability.

FAQ

Major transport and utility corridors can divide habitats into smaller, isolated patches, limiting wildlife movement and reducing genetic diversity over time.

Ecological fragmentation is often intensified when corridors cut through wetlands, forests, or river systems.

Urban planners sometimes address this by adding wildlife crossings, preserving green buffers, or clustering infrastructure along existing routes to minimise new disruption.

Infrastructure materials such as asphalt, metal, and concrete absorb and radiate heat, creating localised temperature increases known as urban heat islands.

Multi-storey transport interchanges, dense road networks, and large car parks often produce warmer microclimates.

Green roofs, permeable surfaces, and shade structures can help moderate these effects by providing cooling and reducing heat storage.

Older infrastructure typically relies on outdated designs, less efficient materials, and less sustainable technologies.

As systems age, leakage, energy loss, and maintenance failures become more common, leading to wasted resources and higher pollution levels.

Modern upgrades tend to include improved insulation, digital monitoring, and enhanced filtration that reduce environmental impacts.

Stormwater drains often channel runoff directly into rivers or coastal waters without treatment.

This runoff can carry:

vehicle oils

heavy metals

litter and plastics

fertiliser and pesticide residues

Even well-maintained systems can rapidly transport pollutants during rainfall events, especially in high-traffic or industrial zones.

Large underground projects require extensive excavation, which can disrupt groundwater flows and increase sediment displacement.

Benefits include reducing above-ground land consumption and freeing surface space for green areas.

However, construction can destabilise soils, alter water tables, and increase energy demands for pumping, ventilation, and long-term maintenance.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which urban infrastructure can contribute to increased surface runoff in cities.

(3 marks)

Mark Scheme

Identifies a relevant type of infrastructure (e.g., roads, pavements, rooftops). (1 mark)

Explains that these create impervious surfaces that prevent water from infiltrating the soil. (1 mark)

Clearly links this to higher levels of surface runoff or increased flood risk. (1 mark)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how differences in infrastructure investment can lead to environmental inequalities within an urban area.

(6 marks)

Mark Scheme

Identifies at least one form of infrastructure relevant to environmental quality (e.g., waste facilities, major roads, energy systems). (1 mark)

Describes how uneven investment results in differing environmental conditions (e.g., poorer neighbourhoods receiving more polluting facilities or fewer upgrades). (1–2 marks)

Explains environmental consequences such as higher pollution exposure, increased hazard vulnerability, or lack of green space. (1–2 marks)

Uses an appropriate example or case (can be real or hypothetical but must be geographically plausible). (1 mark)

Provides a clear analytical link between the infrastructure pattern and the resulting environmental inequality. (1 mark)