AP Syllabus focus:

‘Infrastructure influences social outcomes by affecting access to jobs, schools, health care, and public space.’

Urban infrastructure shapes how residents move, work, learn, and interact, making it a core factor in determining the social opportunities, barriers, and inequalities experienced within cities.

Infrastructure and Its Social Role

Infrastructure forms the backbone of urban life, directly structuring who can reach essential services and how reliably they can do so. Infrastructure and society are closely linked because physical systems—transportation, water, sanitation, energy, and communication—organize daily routines and influence long-term social mobility.

Infrastructure: The systems and networks that support daily urban functions, including transportation, utilities, and communication services.

Because infrastructure is unevenly distributed within many metropolitan areas, these systems often reinforce existing spatial patterns of wealth, deprivation, and segregation.

Access to Services as a Social Outcome

The AP specification highlights that infrastructure affects access to jobs, schools, health care, and public space, making it essential in shaping quality of life. These impacts appear in several interconnected ways:

Transportation and Access to Employment

Transportation networks determine commuting possibilities and labor market reach.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors use dedicated lanes, median stations, and priority at intersections to provide faster and more reliable service than mixed-traffic buses. This photo of the Van Ness BRT in San Francisco shows a bus stopping at a central platform in a red transit-only lane, illustrating how transit infrastructure organizes daily mobility and access to employment, schools, and services. Details such as the specific route and lane coloring go beyond AP Human Geography requirements but help visualize how transportation design affects social opportunities in a city. Source.

When reliable modes of travel connect neighborhoods to major employment centers, residents gain broader access to job opportunities. In contrast, communities isolated from transit often face persistent economic disadvantages.

High-capacity transit (rail, bus rapid transit, subways) expands the distance residents can travel at reasonable cost and time.

Road networks and highways influence where firms locate, often shaping suburban job clusters.

Inadequate transit service limits employment options, deepening socioeconomic divides.

Transportation access also influences time-poverty, as long commutes reduce the hours available for childcare, leisure, education, and civic participation.

Schools, Education, and Infrastructure Quality

Urban school quality is closely tied to infrastructure conditions within surrounding neighborhoods. Educational access depends on:

Safe travel routes, including sidewalks, crossings, and school-bus systems.

Technological infrastructure, such as broadband internet, which affects digital learning and homework completion.

Utilities and building quality, which determine classroom comfort, ventilation, and safety.

Unequal investment in these systems can reinforce spatial patterns of educational achievement, contributing to long-term differences in human capital formation.

Health Care Access and Environmental Conditions

Infrastructure plays a central role in shaping health outcomes. Urban residents depend on physical networks that determine whether health services are reachable and whether environmental conditions support healthy living.

Transportation and Health Facilities

Hospitals, clinics, and emergency services require dependable road and transit systems. Limited transportation routes or infrequent schedules can delay medical care, increase health disparities, and reduce preventive care.

Water, Sanitation, and Public Health

Clean water and sanitation infrastructure reduce disease risks and support healthy urban environments.

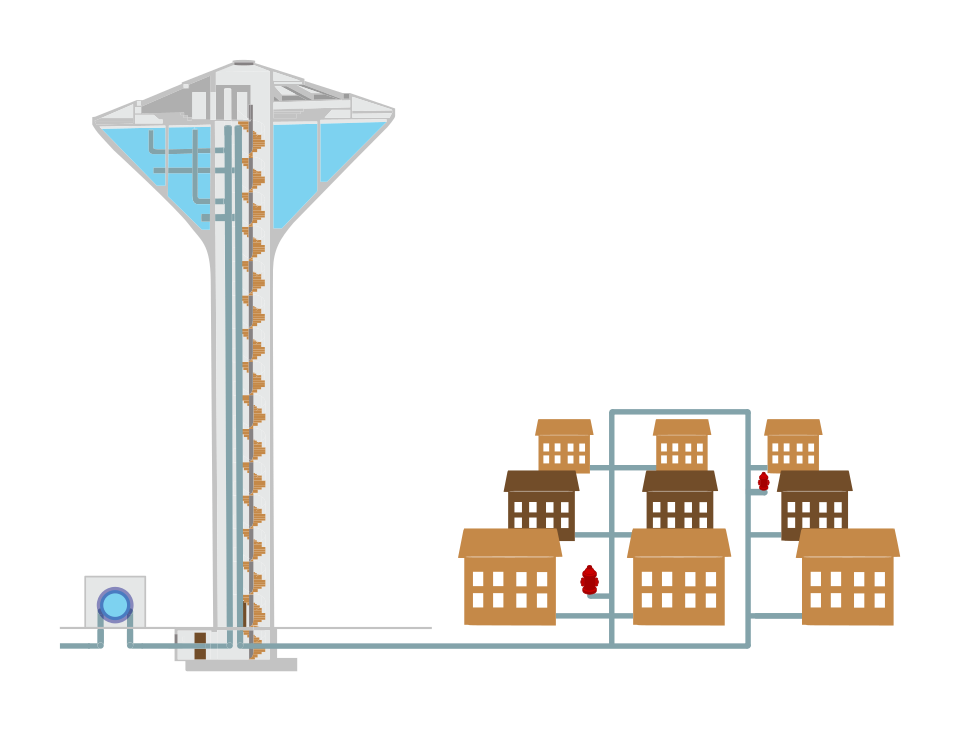

This diagram illustrates a municipal water distribution system in which treated water is pumped into a tower and then flows by gravity through mains to homes and fire hydrants. It helps students see how an interconnected network of pumps, storage, and pipes makes safe drinking water available to households and critical services across a city. The inclusion of specific component designs, such as the cross-sectioned water tower and labeled hydrants, adds technical detail beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but strengthens understanding of urban water infrastructure as a citywide system. Source.

Failing or underfunded systems often correlate with:

Higher rates of waterborne illness

Increased exposure to pollutants

Infrastructure stress during storms or drought

Sanitation Infrastructure: Systems that manage wastewater, sewage, and solid waste to maintain public health and environmental quality.

Infrastructure gaps in sanitation disproportionately affect marginalized communities, revealing how physical systems become drivers of urban inequality.

Public Space, Social Life, and Safety

Public spaces shape social cohesion and community well-being.

Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan demonstrates how a well-designed urban park provides accessible green space within a dense commercial district. People spread out across the lawn and surrounding seating areas, using the park for rest, conversation, and informal recreation, which illustrates how public-space infrastructure supports social interaction and mental well-being. The specific New York Public Library backdrop and skyscraper skyline are not required by the AP Human Geography syllabus but highlight how public spaces can coexist with intensive urban development. Source.

Parks and Recreational Spaces

Park access depends on transportation networks, pedestrian infrastructure, and municipal investment. Residents living near well-maintained parks often experience better physical and mental health, while neighborhoods lacking green space face higher heat exposure and fewer opportunities for recreation.

Lighting and Street Infrastructure

Street lighting, sidewalks, and pedestrian crossings influence daily mobility and perceived safety. Well-designed public infrastructure supports:

Social interaction

Night-time access to services

Reduced fear of crime

Enhanced walkability for all age groups

Poorly maintained streets, on the other hand, can isolate communities socially and economically.

Infrastructure Inequality and Social Stratification

Infrastructure investment often follows political and economic priorities, which may not align with residents' needs. Uneven development shapes social outcomes in three major ways:

1. Spatial Inequality

Different neighborhoods receive different levels of service, creating infrastructure deserts where residents lack transit options, high-speed internet, reliable utilities, or safe public spaces.

2. Economic Mobility

Infrastructure determines access to opportunities. A well-connected neighborhood can offer upward mobility, while a poorly connected one may trap residents in cycles of poverty.

3. Social Inclusion and Equity

Infrastructure can integrate diverse communities—or reinforce segregation. For example:

Highways have historically divided neighborhoods along racial or class lines.

Transit routes that bypass lower-income areas reduce access to regional services.

Broadband gaps limit participation in the digital economy.

Infrastructure as a Tool for Social Improvement

Cities use infrastructure planning to improve social outcomes and address disparities. Strategies include:

Transit expansion to underserved neighborhoods

Investments in water and sanitation to eliminate health hazards

Redevelopment of public spaces to promote community interaction

Broadband infrastructure programs to bridge digital divides

These strategies demonstrate that infrastructure is not only a technical system but also a mechanism through which cities can promote fairness, resilience, and improved quality of life for all residents.

FAQ

Infrastructure can influence mobility by determining how easily residents access education, employment and essential services.

Areas with consistent investment in transport, digital connectivity and utilities tend to accumulate advantages over time, attracting businesses, higher-skilled workers and further funding.

Neighbourhoods with underdeveloped or outdated infrastructure often experience reduced job accessibility, higher service costs and fewer opportunities for youth, reinforcing cycles of disadvantage across generations.

Underserved areas often reflect historic planning decisions, political inequalities and uneven municipal funding structures.

Local governments may prioritise investment where tax revenue is highest or where political influence is concentrated.

In growing cities, rapid expansion can outpace infrastructure provision, leaving peripheral or low-income communities with delayed upgrades and insufficient public services.

Digital connectivity has become a core component of social participation, affecting access to schooling, employment and civic engagement.

Limited broadband availability can create digital divides that mirror existing socioeconomic inequalities.

Improved digital infrastructure supports remote work, online learning and communication networks, making it increasingly important for reducing urban inequalities.

Public spaces allow residents from different backgrounds to interact, reducing social isolation and building a sense of shared identity.

Well-maintained parks and plazas also support informal economies, cultural events and community-led activities, strengthening social ties.

Lighting, seating, and accessible paths encourage varied use of the space, enabling people of different ages and abilities to participate in public life.

Frequent disruptions in water supply, transport, energy or sanitation can reduce confidence in authorities’ ability to manage urban systems.

When failures disproportionately affect marginalised neighbourhoods, perceptions of inequity and neglect often intensify.

Effective, transparent responses to failures—such as timely repairs, public communication and equitable resource allocation—play a key role in rebuilding trust.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain one way in which urban infrastructure can influence residents’ access to employment opportunities.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant way infrastructure affects employment access (e.g., efficient public transport connecting neighbourhoods to job centres).

• 1 mark for explaining why this matters for residents (e.g., reduces travel time, increases the range of reachable jobs, or allows low-income workers to commute affordably).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Using specific examples, analyse how differences in the quality of urban infrastructure can lead to unequal social outcomes within a city.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying that infrastructure quality varies across neighbourhoods.

• 1 mark for explaining how better transport, water, sanitation, or digital infrastructure improves social outcomes (e.g., job access, educational attainment, or health).

• 1 mark for explaining how poor infrastructure can restrict opportunities (e.g., limited access to health care or unreliable utilities).

• 1 mark for providing at least one specific, relevant urban example.

• 1 mark for showing a clear causal link between infrastructure differences and unequal social outcomes (e.g., spatial inequality, segregation, or unequal life chances).