AP Syllabus focus:

‘Sustainable zoning can promote mixed land use and walkability, allowing people to reach daily needs with fewer car trips.’

Mixed land use and walkability reshape urban environments by clustering daily activities together, reducing dependence on cars, and supporting more sustainable, accessible neighborhoods within metropolitan areas.

Mixed Land Use and Its Urban Significance

Mixed land use refers to the combination of residential, commercial, institutional, and recreational functions within the same area. This development pattern contrasts with traditional single-use zoning that separates housing from workplaces and services. By placing diverse land uses in close proximity, mixed-use zoning reduces travel distances and supports a more efficient spatial arrangement of urban functions.

Mixed Land Use: The deliberate planning and zoning strategy that integrates multiple types of land uses—such as housing, shops, offices, and public spaces—within the same district or block.

Mixed-use planning encourages greater urban vibrancy, which describes the presence of lively, pedestrian-friendly environments. Shops, cafés, parks, and housing situated together create activity throughout the day. This supports a more efficient use of infrastructure because streets, transit, utilities, and public amenities serve multiple functions simultaneously.

Core Characteristics of Mixed Land Use

Mixed land use typically exhibits the following spatial and structural qualities:

• Proximity of activities, where daily needs are located within a short walking or cycling distance.

• Vertical mixing of land uses, such as housing above ground-floor retail.

• Fine-grained block patterns that support permeability and multiple route options.

• Accessible public spaces, including sidewalks, plazas, and community facilities.

• Transit-supportive densities, where population and job concentrations can sustain reliable public transportation.

These characteristics reflect an intentional shift away from large, single-use districts toward interwoven patterns of living and working.

In a mixed land use neighborhood, housing, shops, offices, and civic spaces are located close together rather than separated into single-use zones.

A vertical mixed-use building with ground-floor retail and upper-story housing in downtown Kirkland, Washington. The combination of shops and residences in the same structure encourages short walking trips instead of car journeys. The image also includes minor extra architectural details not required by the syllabus but useful for illustrating realistic mixed-use streetscapes. Source.

Walkability as a Foundation of Sustainable Urban Design

Walkability describes how easily people can navigate an area on foot. It depends on street connectivity, safety, density, and access to destinations. The link between mixed land use and walkability is strong: when destinations are close and routes are direct, walking becomes a practical, appealing mode of travel.

Walkability: The degree to which the built environment supports safe, comfortable, and convenient pedestrian travel.

Walkability contributes to urban sustainability, meaning development that supports long-term environmental, economic, and social well-being. When more people walk instead of drive, cities reduce traffic congestion, fuel consumption, and emissions while improving health outcomes and neighborhood interaction.

Normal urban street patterns vary in walkability depending on factors such as sidewalk coverage, intersection density, and perceived safety. Mixed-use zones usually score higher because they offer more destinations per unit area.

Key Elements of Walkable Environments

Urban geographers identify several built-environment elements that support daily pedestrian travel:

• Density: Higher densities place more people near services, making facilities viable without large parking areas.

• Connectivity: Grid-like or highly linked street networks shorten travel paths and increase route choice.

• Pedestrian infrastructure: Sidewalks, crosswalks, lighting, and traffic-calming measures enhance safety.

• Human-scale design: Buildings close to the street, active façades, and limited block lengths maintain visual interest and comfort.

• Access to public transit: Transit stops within walking distance extend mobility beyond the neighborhood.

Together, these features enable households to complete errands and leisure activities without relying heavily on motor vehicles.

Designers often divide sidewalks into functional zones so that people walking have a clear, unobstructed path even when buildings have outdoor seating or street trees and benches are added.

This diagram illustrates a sidewalk divided into a frontage zone, pedestrian through zone, and street-furniture or buffer zone. These components support walkability by giving pedestrians safe, unobstructed space while accommodating benches, outdoor dining, and landscaping. The image includes extra technical labels beyond the AP syllabus but helps clarify how walkable sidewalks are structured. Source.

How Mixed Land Use Supports Sustainable Zoning Goals

Sustainable zoning aims to reduce the environmental footprint of cities while improving residents’ quality of life. Mixed land use is a central tool for achieving these goals because it clusters destinations, promotes non-motorized travel, and reduces the need for extensive parking and road expansion.

Travel Behavior and Accessibility

Mixed-use zoning directly affects travel behavior in the following ways:

• Shorter trip distances reduce the necessity for car ownership and encourage walking or biking.

• Multimodal accessibility, where transit, cycling, and walking options coexist, becomes more feasible due to concentrated development.

• Reduced peak-hour congestion occurs when residents live closer to workplaces, schools, and shops.

Improved accessibility also enhances inclusivity by supporting groups less able to drive, such as the elderly, youth, and low-income populations.

Environmental and Social Benefits

The environmental benefits of mixed land use include:

• Lower greenhouse gas emissions from reduced vehicle miles traveled.

• Decreased land consumption and preservation of open space through compact development.

• Smaller ecological footprints associated with more efficient infrastructure use.

Social and economic benefits include:

• Increased street-level activity, which can deter crime and support surveillance through “eyes on the street.”

• Stronger local economies, as small businesses attract foot traffic and serve nearby residents.

• Improved public health, as walkability promotes daily physical activity.

• Enhanced community interaction, as pedestrian-oriented design facilitates informal social encounters.

These advantages illustrate why mixed-use and walkable cities are often viewed as more resilient and adaptable amid shifting demographic, economic, and environmental conditions.

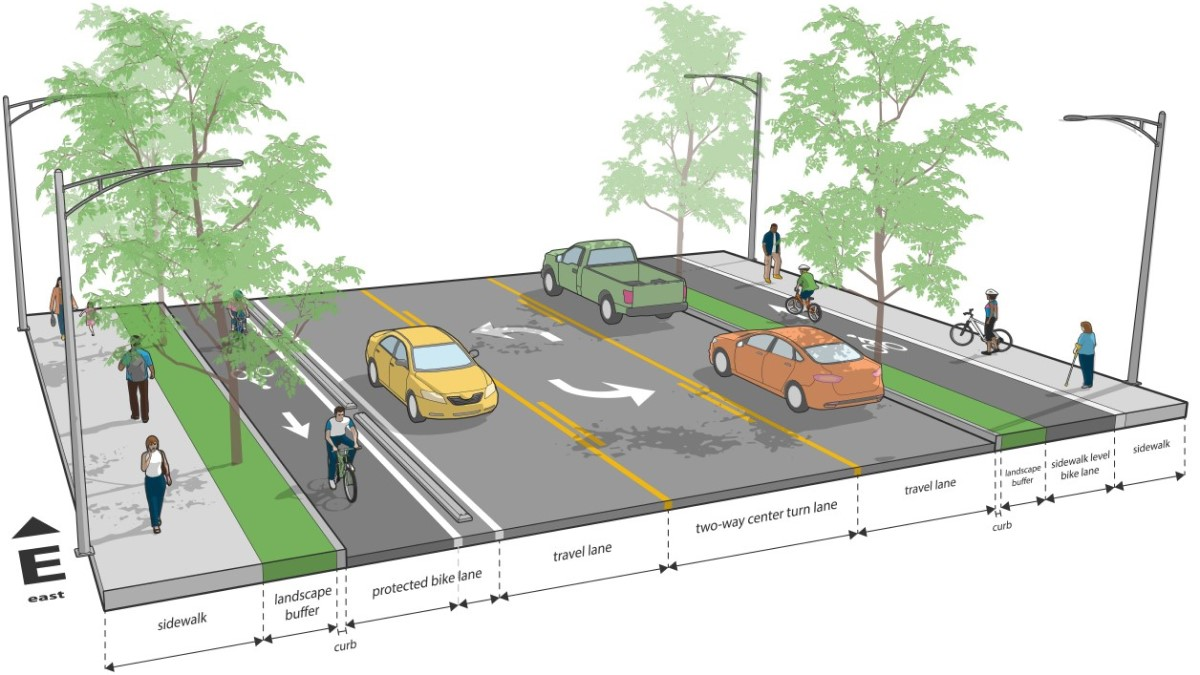

Complete streets with wide sidewalks, protected bike lanes, street trees, and frequent crossings increase perceived safety and make walking an attractive alternative to driving between nearby land uses.

This street cross-section includes sidewalks, landscaped buffers, protected bike lanes, and travel lanes, illustrating how multimodal street design enhances walkability in mixed-use areas. The arrangement supports safe movement for pedestrians and cyclists while accommodating vehicles. Extra engineering labels are present but help clarify how different street components work together. Source.

Interactions with Zoning and Planning Policies

Many U.S. cities historically relied on Euclidean zoning, which strictly separated residential, commercial, and industrial uses. This structure frequently encouraged car dependency and low-density sprawl. In contrast, form-based zoning and performance zoning allow more flexible integration of land uses.

Mixed land use depends on strategic zoning reforms such as:

• Reducing minimum parking requirements to free land for housing and public space.

• Allowing accessory dwelling units or mixed-use buildings in traditional residential zones.

• Permitting higher-density infill development to increase accessibility within urban cores.

• Aligning zoning with transit investments, ensuring that high-capacity transit corridors support compact, mixed-use growth.

These policies help cities transition toward more sustainable urban landscapes that prioritize walkability, accessibility, and environmental stewardship.

FAQ

Mixed land use compresses the distances between home, work, and leisure, which alters how people organise their daily routines. Residents spend less time travelling and more time engaging in local activities.

This often leads to:

• Increased use of neighbourhood shops and public spaces

• More flexible trip chaining, where errands are combined into a single outing

• Greater social visibility as more people are on foot throughout the day

These combined effects create a denser web of interactions within the local environment.

Small businesses benefit from the steady pedestrian flow generated by diverse land uses. Foot traffic is more consistent across the day because different functions—such as cafés, offices, and homes—activate the area at different times.

In contrast, single-use commercial zones experience peaks and troughs tied to specific business hours. Mixed-use settings reduce this volatility, giving local shops a stable customer base and improving long-term economic resilience.

Transforming car-centred areas relies on targeted physical interventions. Effective features include:

• Narrowed vehicle lanes to slow traffic

• Raised crossings and extended kerb corners for safer pedestrian movement

• Street trees and lighting to improve comfort and visibility

• Ground-floor design requirements that ensure active façades and avoid blank walls

These changes promote human-scale environments that encourage walking rather than driving.

Mixed-use areas generate more frequent, informal interactions because residents encounter one another in shared spaces such as local shops, cafés, and pavements.

Over time, this creates:

• Stronger place attachment as people use social spaces daily

• Localised networks of support and communication

• A sense of collective stewardship, as visible activity encourages residents to maintain and care for shared environments

These conditions help build a distinctive and cohesive neighbourhood identity.

Walkable mixed-use environments offer amenities within close reach—shops, transit, parks—which buyers and renters increasingly prioritise. High accessibility becomes a valuable commodity.

Property values typically rise due to:

• Reduced transport costs for households

• Greater desirability of lively, human-scale streets

• Stronger local economies supporting nearby services

However, these increases can raise affordability concerns, making careful planning essential to maintain social diversity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how mixed land use can increase walkability within an urban neighbourhood.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying that mixed land use places different activities or services close together.

• 1 mark for explaining that shorter distances make walking a practical or convenient mode of travel.

• 1 mark for linking this to reduced reliance on cars or improved pedestrian accessibility.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the social and environmental benefits that may result from implementing mixed land use and walkable design in a metropolitan area.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying at least one social benefit (e.g., increased community interaction, improved public health, safer streets).

• 1 mark for explanation of how the social benefit arises (e.g., walkable streets encourage activity and surveillance).

• 1 mark for identifying at least one environmental benefit (e.g., reduced emissions, less land consumption).

• 1 mark for explanation of how the environmental benefit arises (e.g., fewer car trips reduce fuel use and air pollution).

• 1 mark for discussing the overall impact on the urban environment or community.

• 1 mark for a well-reasoned, coherent assessment showing understanding of urban planning concepts.