AP Syllabus focus:

‘Transportation-oriented development clusters housing and jobs near transit, supporting ridership and reducing traffic and emissions.’

Transportation-oriented development (TOD) restructures urban areas around high-quality public transit so residents can live, work, and access services with fewer car-dependent trips.

Understanding Transportation-Oriented Development (TOD)

Transportation-oriented development (TOD) is a planning and urban design approach that organizes housing, employment centers, and essential services within walking distance of major public transit hubs, such as rail stations or bus rapid transit corridors. By concentrating activity around transit, TOD enhances accessibility, increases transit ridership, and reduces reliance on automobiles. This linkage between land-use planning and transportation investment aims to create compact, efficient, and environmentally responsible urban growth patterns.

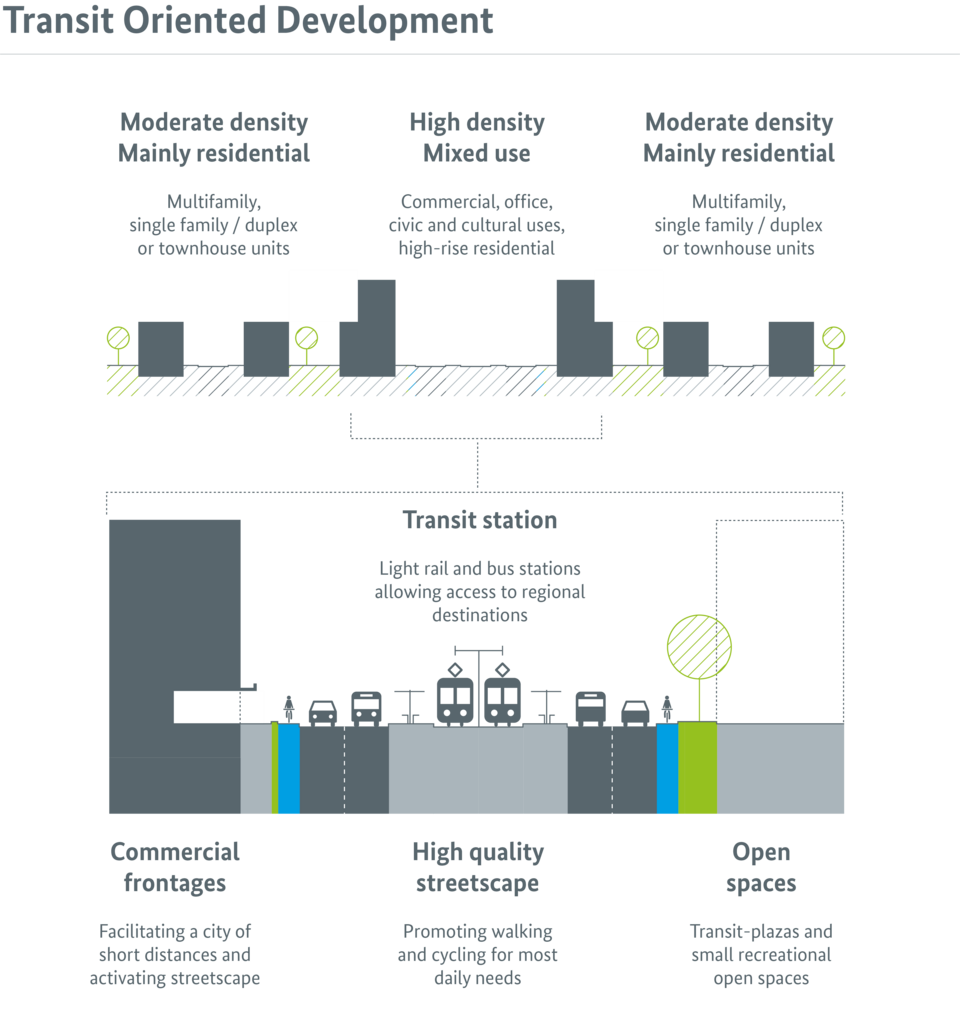

Conceptual diagram of a transit-oriented development (TOD) district, with a central transit stop surrounded by core commercial areas, offices, public spaces, and residential neighborhoods. The figure highlights how density and mixed land uses are highest closest to the station, then gradually transition outward. It includes additional design detail, such as labeled public spaces and secondary areas, beyond the level of specificity required by the syllabus. Source.

Core Principles of TOD

TOD relies on several interrelated design and planning principles that reinforce the connection between transit access and daily urban life.

Density near transit: Higher-density residential and commercial development is clustered closest to transit stations to maximize accessibility.

Mixed land use: Housing, retail, services, and offices are integrated so people can meet daily needs without long trips.

Walkability and pedestrian priority: Streetscapes are designed for safe, comfortable walking with sidewalks, lighting, and reduced vehicle dominance.

Transit accessibility: Frequent, reliable, and high-capacity transit links TOD districts to the broader metropolitan area.

Reduced parking supply: Lower parking requirements encourage transit use and free land for more productive urban functions.

These principles work together to shape neighborhoods with vibrant activity, lower transportation emissions, and improved mobility options.

Why TOD Accelerates Sustainable Urbanization

TOD reshapes how cities grow by aligning transportation and land-use policies, producing multiple geographic and environmental benefits.

Clustering Housing and Jobs Near Transit

TOD brings residential units and employment into closer proximity with major transit routes, allowing residents to travel efficiently between home, work, and services. This spatial concentration supports higher transit ridership and maximizes the return on public investment in infrastructure.

Reducing Traffic and Car Dependence

By locating destinations near transit and creating walkable environments, TOD reduces the need for private automobile travel. Lower car dependence decreases congestion, transportation-related emissions, and household transportation costs. Residents have more mobility choices, and cities experience less pressure to expand roads and parking.

Expanding Accessibility and Equity

TOD can improve access to economic opportunities by connecting diverse populations to job-rich areas through affordable and reliable transit. When paired with inclusive housing policies, TOD can help prevent displacement and ensure that transit-rich neighborhoods serve residents across income levels.

Components of a TOD District

TOD districts include layers of built environment elements and policy frameworks that reinforce connectivity and compact growth.

Land-Use Patterns

High-density residential buildings, including mid-rise and high-rise apartments, support population levels needed to sustain frequent transit service.

Light rail trains pass directly in front of mid-rise apartments in a transit-oriented development (TOD) area served by the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). The image highlights how higher-density housing can be clustered immediately adjacent to a rail corridor to support frequent transit service and reduce car dependence. Some additional contextual details, such as specific branding and surrounding intersection design, go beyond what is required in the AP syllabus but remain helpful for visualizing TOD in practice. Source.

Office and commercial space located close to stations attracts workers and customers traveling by transit.

Community amenities, such as schools, clinics, libraries, and parks, strengthen neighborhood functionality and reduce travel distances.

Urban Design Features

Pedestrian-oriented streets provide continuous sidewalks, crosswalks, and traffic calming measures to promote safety.

Public plazas and open spaces encourage community interaction.

Active ground-floor uses, such as shops and cafés, create inviting streetscapes that increase foot traffic near transit stations.

Transportation Infrastructure

TOD success depends on high-quality transit systems that can support increased ridership. These systems may include:

Heavy rail and commuter rail

Light rail or streetcar lines

Bus rapid transit (BRT)

Frequent local bus routes integrated with station areas

The design of station access points, transit shelters, and multimodal connections (such as bike lanes and shared mobility hubs) further supports efficient movement.

Planning Tools and Policy Mechanisms Supporting TOD

Implementing TOD requires coordinated public policies and development strategies that shape both private investment and public infrastructure.

Zoning and Regulatory Tools

Cities often adjust zoning codes to promote TOD by:

Allowing higher-density and mixed-use development near stations

Reducing minimum parking requirements

Encouraging form-based codes that emphasize building design and pedestrian orientation

Establishing overlay zones that prioritize walkability and transit access

These regulations create an environment where TOD projects can be financially and physically feasible.

Public Investment and Incentives

Local governments may invest in public space improvements, station upgrades, or pedestrian infrastructure to support TOD. Incentives such as tax credits, density bonuses, or expedited permitting can encourage developers to build compact, transit-supportive projects.

Cities may also partner with transit agencies to coordinate land development on publicly owned parcels, especially surrounding stations.

Affordable Housing Strategies

Since increased demand near transit hubs can raise land values, maintaining housing affordability is crucial. Policies may include:

Inclusionary zoning, requiring a percentage of units to be affordable

Land trusts or public land banking

Subsidies or grants supporting low-income housing near transit

These strategies help ensure TOD remains accessible to a broad population.

Geographic Impacts of TOD on Urban Form

TOD reshapes metropolitan geography by concentrating development in nodes connected along transit corridors.

This pattern can create polycentric urban regions, where multiple high-density centers form around transit, reducing pressures to expand outward into low-density sprawl.

TOD also enhances the internal structure of cities by improving accessibility gradients and influencing where businesses choose to locate. Over time, these shifts promote more efficient land use and support sustainable economic growth across the urban system.

FAQ

Funding for TOD often combines public and private investment. Local governments may invest in transit stations, streetscape upgrades, or pedestrian infrastructure, while developers finance residential or commercial construction near transit.

Public–private partnerships are common, particularly when land owned by transport agencies is leased or sold for development.

Cities may also use tools such as tax-increment financing, density bonuses, or reduced parking requirements to encourage TOD investment.

TOD is most successful around high-capacity, frequent transit services because they offer reliable alternatives to driving.

Effective modes include:

• Light rail and heavy rail stations

• Bus rapid transit with dedicated lanes

• Frequent local bus hubs integrated with pedestrian networks

Low-frequency services tend to weaken TOD because they do not provide enough convenience to attract sustained ridership.

Planners consider the station’s expected ridership, the transit mode, and the surrounding neighbourhood’s capacity for growth.

They also evaluate factors such as:

• Existing land values

• Infrastructure availability

• Walkability constraints

• Community preferences expressed through consultation

Higher-capacity rail stations generally support the highest densities, while bus-based TOD may require more moderate levels.

Existing built environments may limit opportunities for new construction, especially where parcel sizes are small or fragmented.

Retrofitting can face challenges including:

• Local opposition to increased density

• Insufficient pedestrian infrastructure

• Zoning that restricts mixed use

• Limited land near transit stations

In many cases, redevelopment occurs gradually as parcels become available or zoning laws are revised.

Modern TOD integrates cycling as a complementary mode that extends access beyond the immediate walkable area.

Typical strategies include:

• Providing safe cycle lanes leading directly to stations

• Installing secure cycle parking or shared mobility hubs

• Allowing limited cycle carriage on trains or buses

This integration increases the effective catchment area of transit stations and reduces dependence on cars even further.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which transportation-oriented development (TOD) can reduce private car use in urban areas.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid mechanism, such as placing housing and jobs closer to transit.

1 mark for explaining how this increases the likelihood of using public transport or walking.

1 mark for linking this to a reduction in car dependence or car trips.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using a named or generic urban area, analyse how transportation-oriented development (TOD) can influence both the spatial structure and the social outcomes of a city.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing the concept of TOD (for example, clustering development around transit nodes).

1–2 marks for explaining impacts on spatial structure, such as increased density near stations, formation of activity nodes, or changes in land-use patterns.

1–2 marks for analysing social outcomes, such as improved accessibility, affordability implications, or potential risks of displacement.

1 mark for using an appropriate example to support the explanation.