AP Syllabus focus:

‘Greenbelts and slow-growth strategies manage expansion by preserving open space and guiding where new development can occur.’

Greenbelts and slow-growth cities represent planning strategies that deliberately limit outward urban expansion, protect natural land, encourage sustainability, and manage long-term development to balance environmental, economic, and social needs.

Greenbelts: Controlling Expansion Through Protected Open Space

Greenbelts are bands of protected open land encircling or surrounding a city to limit outward urban growth.

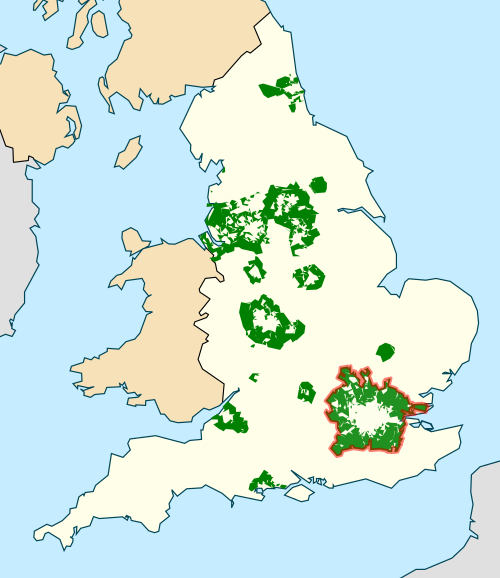

Map showing the Metropolitan Green Belt around London and additional green belts across England. The shaded regions highlight protected land that restricts outward expansion and preserves open space. The map includes extra regional greenbelts not required by the AP syllabus, but they help illustrate the broad application of greenbelt planning. Source.

They help planners shape the boundaries of development and direct where future construction can occur. Greenbelts serve as both environmental and spatial planning tools, influencing the density, layout, and sustainability of nearby urban areas.

Purposes and Functions of Greenbelts

Greenbelts operate by drawing a firm line between the built environment and undeveloped land. This line is intentionally difficult to cross for new construction, which directs growth inward rather than outward. Their usefulness can be understood through several key functions:

Limiting urban sprawl, preventing low-density development from extending indefinitely.

Protecting farmland, forests, and ecological zones that would otherwise be at risk of conversion to residential or commercial uses.

Encouraging infill development, which directs investment toward underused or vacant land within existing urban boundaries.

Maintaining separation between cities, preventing the merging of metropolitan areas into continuous urban corridors.

Providing recreational and environmental value, offering accessible green space for residents and supporting biodiversity.

Because greenbelts restrict outward expansion, they influence land-use patterns inside the boundary, often increasing density and encouraging mixed-use development.

How Greenbelts Shape Urban Patterns

By design, greenbelts alter the spatial distribution of development. Cities with strong greenbelt regulations typically exhibit more compact growth, with a clearer distinction between urban and rural land. This can foster walkability, reduce infrastructure costs, and strengthen transit systems.

However, greenbelts can also contribute to unintended consequences. Limited land supply within the boundary may increase property values and contribute to affordability challenges if not paired with proactive housing policies. As a result, planners must carefully coordinate greenbelt rules with zoning and development incentives.

Slow-Growth Cities: Managing the Pace of Urban Expansion

Slow-growth policies are planning strategies that intentionally moderate the pace and scale of development. Rather than fully restricting growth, slow-growth cities manage it through regulations and long-term planning frameworks that guide how quickly land can be developed, infrastructure can be extended, and new housing can be approved.

Slow-Growth City: A city that uses policies to intentionally limit or pace development to reduce environmental impacts, protect resources, or maintain quality of life.

Slow-growth strategies rely on controlled development timelines to ensure that growth aligns with sustainability goals and infrastructure capacity.

Photograph of the urban growth boundary near Bull Mountain in Oregon, illustrating the sharp divide between farmland and suburban development. The contrast shows how a UGB concentrates growth within a defined limit while protecting open land outside. The image contains local Portland-area details not required by the syllabus but effectively visualizes the planning concept. Source.

Key Elements of Slow-Growth Strategies

Slow-growth approaches often involve comprehensive policy tools that shape the region’s long-term form. Important components include:

Growth caps placing limits on the number of new housing units permitted annually.

Urban growth boundaries (UGBs) defining where development may expand over time.

Infrastructure phasing, which restricts new development until utilities, transportation corridors, or schools can support added population.

Preservation zoning, which protects natural landscapes and agricultural land from rapid conversion.

Community-centered review processes that evaluate the impact of new projects on transportation, the environment, and municipal services.

Each of these tools reinforces the goal of aligning growth with environmental protection and community priorities.

Why Cities Adopt Slow-Growth Policies

Slow-growth planning reflects concerns about rapid or unmanaged expansion. Cities often adopt these policies to address:

Environmental protection, preventing habitat loss, water contamination, and degradation of natural landscapes.

Infrastructure limitations, ensuring roads, water systems, and schools are not overwhelmed.

Quality-of-life preservation, preventing overcrowding, congestion, and loss of community character.

Long-term sustainability, integrating urbanization with resource management and climate resilience.

These motivations align closely with the AP syllabus emphasis on how sustainable planning guides where development should occur.

Interactions Between Greenbelts and Slow-Growth Approaches

Greenbelts and slow-growth cities are frequently used together because they reinforce each other’s goals. Greenbelts provide a spatial boundary that limits outward expansion, while slow-growth policies regulate how and when development occurs within that boundary. Together, they promote compact urban form, protect natural land, and encourage environmentally responsible growth patterns.

Benefits of Combining These Approaches

When used in tandem, these strategies can:

Strengthen sustainable land-use patterns by preserving undeveloped land and encouraging efficient urban form.

Support long-term regional planning, ensuring growth is both environmentally and economically manageable.

Enhance public access to green space, contributing to well-being and environmental health.

Promote more efficient use of existing infrastructure, decreasing the need to extend roads, utilities, and services into new areas.

Cities employing both strategies often develop clearer, more intentional long-range plans that balance development needs with conservation priorities.

Challenges and Criticisms

Although greenbelts and slow-growth strategies provide significant sustainability benefits, they also generate challenges that planners must address.

Housing affordability issues may arise if land is restricted without increasing housing supply.

Leapfrog development, where growth jumps past the greenbelt and forms distant suburbs, can increase car dependence.

Development pressure may intensify inside the controlled area, creating tension between density goals and community preferences.

Economic limitations may surface in regions reliant on construction or expansion for growth.

These challenges highlight the need for coordinated zoning, transportation planning, and affordable housing programs when implementing greenbelts and slow-growth policies.

FAQ

Greenbelts often increase the density of development within the boundary, which can shorten average travel distances if housing is closer to jobs and services.

However, if housing demand is high and alternatives are limited, some residents may commute from beyond the greenbelt, creating longer-distance travel patterns.

This can result in a split effect: improved walkability and transit use within the boundary, but potentially longer car commutes from outside it.

Planners typically assess:

Existing natural features such as rivers, forests, and agricultural land.

Land at high risk of development pressure.

Regional ecological corridors that would benefit from protection.

Distances needed to maintain separation between neighbouring settlements.

They also consult long-term regional plans to ensure the boundary supports future housing, employment, and infrastructure needs.

Greenbelt boundaries may be reviewed to accommodate population growth or respond to housing shortages.

Cities sometimes adjust boundaries to include targeted development sites while expanding protection elsewhere, keeping overall green space intact.

Revisions usually occur following demographic studies, infrastructure assessments, and public consultation processes that identify changing regional needs.

Slow-growth cities often rely on negotiated planning processes.

This can include:

Development agreements linking approvals to sustainability measures.

Environmental impact assessments that limit or reshape proposed projects.

Community hearings where compromises are reached on density, open space, and infrastructure timing.

By creating formal review stages, cities aim to balance economic interests with land-use protection.

Slow-growth policies can influence competitiveness in several ways.

They may reduce short-term development activity, which can constrain construction-related employment or tax revenue.

However, they can also enhance long-term appeal by preserving environmental quality, reducing congestion, and ensuring infrastructure keeps pace with growth.

Cities that implement slow-growth policies strategically often market themselves as high-quality, sustainable places to live and work.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which a greenbelt can help limit urban sprawl.

Mark Scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a correct effect (e.g. restricting outward expansion).

1 mark for explaining how the greenbelt prevents continuous low-density development.

1 mark for linking this to a reduced spread of housing or commercial land beyond the boundary.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how slow-growth policies can influence the long-term spatial structure of a city.

Mark Scheme (6 marks total)

1 mark for defining or describing a slow-growth policy.

1 mark for correctly identifying at least one slow-growth tool (e.g. growth caps, urban growth boundaries, infrastructure phasing).

1–2 marks for explaining how these policies shape spatial outcomes (e.g. denser development, protection of rural land, limited outward expansion).

1–2 marks for providing relevant examples that support the explanation (e.g. Portland’s urban growth boundary influencing compact urban form).