AP Syllabus focus:

‘Criticisms can include higher housing costs, possible de facto segregation, and potential loss of historical or place character.’

Urban sustainability initiatives aim to reduce environmental impacts and improve livability, yet they can generate unintended outcomes that complicate equitable and inclusive urban development. These notes examine key criticisms.

Higher Housing Costs

Sustainability-oriented policies, while beneficial for long-term urban resilience, can inadvertently increase housing costs for residents. This often happens when regulations, design requirements, or limited development zones constrain the housing supply within desirable, walkable areas. Rising demand for compact, transit-accessible neighborhoods can push prices higher and intensify affordability challenges.

Mechanisms Behind Rising Costs

Several processes shape these patterns:

Increased demand for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods as amenities, transit access, and environmental quality improve.

Zoning restrictions that limit density or concentrate development only in certain districts.

Green design standards that raise construction costs for developers.

Amenity-driven competition, where households bid up prices to live in revitalized neighborhoods.

Gentrification Pressures

Sustainability initiatives can align with gentrification, defined as the process in which reinvestment and new amenities attract higher-income residents, leading to rising property values and displacement risks.

Gentrification: A form of neighborhood change in which reinvestment and rising demand increase housing costs and potentially displace lower-income residents.

Although gentrification is not an inevitable result of sustainable planning, it is a frequently cited critique, particularly when policy goals do not explicitly address affordability or displacement prevention.

Street scene of a renovated corner building in Budapest associated with gentrification. Refurbished façades and higher-end ground-floor uses illustrate reinvestment that can increase local property values and rents. This specific example includes contextual architectural details beyond the syllabus but clearly shows the visual characteristics of gentrifying areas. Source.

Possible De Facto Segregation

Efforts to create compact, transit-oriented, or aesthetically cohesive neighborhoods may unintentionally reproduce de facto segregation, which is segregation created by socioeconomic forces and market conditions rather than legal requirements. Many sustainability strategies target urban cores or affluent suburbs, where high land values or strict zoning can exclude lower-income groups.

Pathways to Socio-Spatial Inequality

High amenity concentrations raise costs, limiting access for marginalized communities.

Strict land-use controls, such as height restrictions or minimum lot sizes, effectively price out many households.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) near new stations may increase local rents faster than affordability policies can respond.

Historic preservation mandates may prevent affordable housing construction in desirable districts.

These dynamics can reinforce uneven access to jobs, services, and environmental benefits, counteracting sustainability goals that prioritize inclusivity.

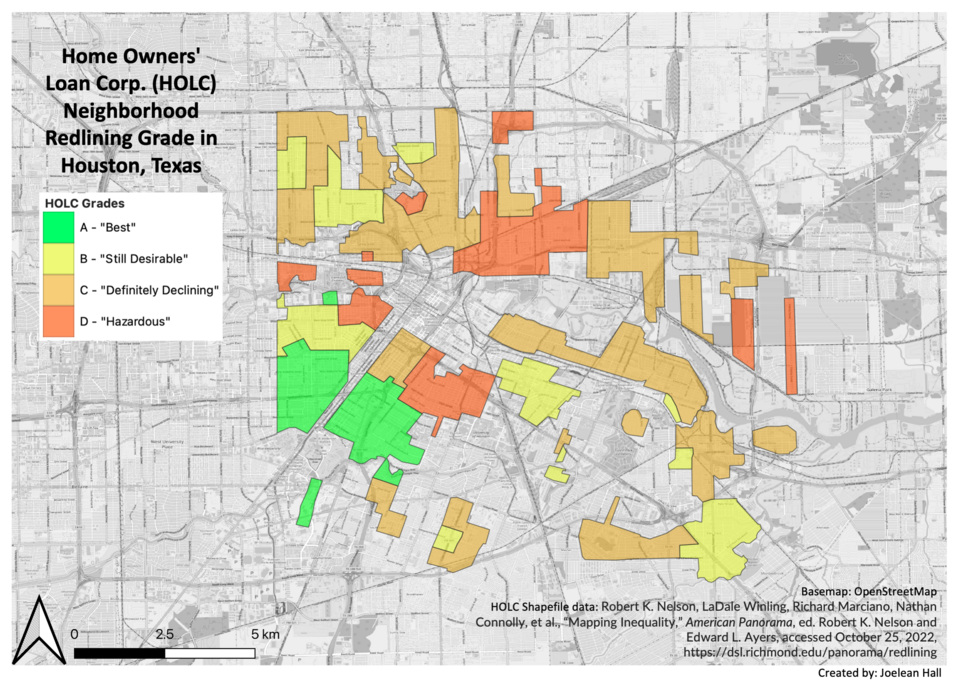

HOLC neighborhood grades in Houston, Texas, showing how mortgage lending risk categories shaped access to credit and investment. Red and yellow zones were historically labeled “hazardous” or “declining,” reinforcing segregation and uneven urban development. This U.S.-specific example provides more historical detail than required but clearly illustrates de facto segregation. Source.

Potential Loss of Historical or Place Character

Another criticism focuses on the aesthetic and cultural impacts of sustainability-focused development. New mixed-use buildings, modern design codes, or large redevelopment projects can conflict with existing architectural styles, community identities, and long-established patterns of land use.

Tension Between Innovation and Preservation

Residents may perceive sustainability initiatives as threats to local character when:

Redevelopment replaces long-standing community landmarks, small businesses, or cultural institutions.

Uniform design guidelines create a sense of placelessness by reducing architectural diversity.

Infrastructure upgrades, such as new transit corridors, alter the spatial configuration of neighborhoods.

Place character is connected to cultural identity, collective memory, and social cohesion; thus, altering it can provoke strong community resistance.

Residential streetscape in Detroit’s Indian Village Historic District, illustrating a strong sense of place character expressed through consistent architecture and tree-lined avenues. Such environments can be sensitive to redevelopment or sustainability initiatives that alter visual identity. This example includes location-specific detail but effectively conveys what communities seek to preserve. Source.

Governance, Participation, and Equity Concerns

Many criticisms stem from concerns about who benefits and who participates in sustainability planning. If decision-making is dominated by developers, planners, or political elites, initiatives may reflect their priorities rather than community needs. Limited public participation can deepen mistrust and reduce the effectiveness of sustainability programs.

Unequal Distribution of Benefits

Critics argue that sustainability initiatives often prioritize high-visibility projects—such as greenbelts, pedestrian districts, or bike lanes—over basic community needs. When investments cluster in already advantaged areas, disparities widen. Challenges include:

Underinvestment in marginalized neighborhoods, where aging infrastructure and environmental burdens persist.

Concentration of green amenities in wealthy districts.

Inadequate affordability measures, allowing displacement to outlying areas with fewer services.

Constraints on Development and Economic Opportunities

Some sustainability policies, particularly growth boundaries or strict zoning, may restrict the amount of land available for housing or business expansion. While intended to curb sprawl, these constraints can produce economic trade-offs.

Land-Use Limitations

Urban growth boundaries (UGBs) contain development within set limits, but if housing demand grows faster than supply, prices may rise sharply.

Preservation of open space may reduce available land for job-generating industries.

Stringent building codes designed for energy efficiency can increase upfront development costs, discouraging small builders.

These constraints shape the economic geography of metropolitan areas and influence long-term affordability and competitiveness.

Technological and Infrastructure Challenges

Sustainability initiatives often rely on new technologies, expanded transit systems, and upgraded energy or water infrastructure. Implementation challenges may lead to financial burdens, uneven service provision, or gaps between planning and outcomes.

Key Issues

High initial costs for infrastructure upgrades.

Uneven rollout of green technologies, leaving some neighborhoods behind.

Maintenance burdens that strain local government budgets.

These challenges reinforce the need for long-term planning, consistent funding, and attention to equity when designing sustainability policies.

FAQ

Sustainability schemes can shift local political power by attracting new, typically higher-income residents who participate more actively in planning processes. This can change whose priorities dominate neighbourhood discussions.

Existing residents may feel their needs are overshadowed as planning boards respond to demands for amenities such as cycling lanes or green spaces rather than focusing on affordability or essential services.

These shifts can create tension between long-term residents seeking stability and newer groups advocating design-oriented improvements.

Resistance often arises from concerns about social or cultural change rather than environmental impacts. Residents may worry that new developments will accelerate gentrification or bring unfamiliar architectural styles.

Communities also fear that projects will raise living costs or threaten their sense of identity. In areas where previous redevelopment has caused displacement or upheaval, trust in planning authorities may already be low.

Historic preservation can conflict with sustainability when restrictions prevent the installation of renewable energy systems or energy-efficient retrofits.

In some cases, strict design rules limit infill development, reducing opportunities for affordable housing or mixed-density building.

This can reinforce exclusivity in preserved districts.

It may push development to less regulated areas, increasing sprawl and vehicle dependence.

Streetscape upgrades, pedestrianisation, or green design improvements can raise property values, pushing up commercial rents. Small, long-standing businesses may struggle to absorb these costs.

Additionally, redevelopment can shift the customer base toward higher-income residents or tourists, altering demand patterns and favouring larger or more upscale retailers.

The resulting commercial turnover can erode the local identity and diversity that once defined the district.

New transit lines often increase land values around stations, making nearby housing less affordable and fuelling anxiety about displacement.

Construction impacts, such as noise or temporary street closures, can disrupt local life and harm community cohesion.

If benefits are perceived to flow primarily to new residents or commercial investors, existing communities may view the project as imposed rather than collaborative, deepening mistrust of urban planning authorities.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which sustainable urban development initiatives may unintentionally increase housing costs in a metropolitan area.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid mechanism (e.g., increased demand for walkable, amenity-rich areas).

1 mark for explaining how the mechanism raises housing costs (e.g., competition drives up prices).

1 mark for linking the process specifically to sustainability initiatives (e.g., green design standards raise construction costs).

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how sustainability-focused planning can contribute to both de facto segregation and the loss of place character within urban neighbourhoods.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for describing how sustainability planning can contribute to de facto segregation (e.g., high property values in transit-oriented areas exclude lower-income residents).

1–2 marks for explaining how sustainability initiatives may lead to loss of place character (e.g., modern redevelopment replacing historic buildings).

1–2 marks for using appropriate examples and providing analytical commentary (e.g., showing cause–effect relationships, discussing impacts on social cohesion or access to services).