AP Syllabus focus:

‘VAR-3.D.1 requires an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of various experimental designs. Detailed notes will cover how the selection of an experimental design is influenced by the research question, the resources at hand, and the nature of the experimental units. Specific examples will illustrate how these factors dictate the choice of one experimental design over another, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the decision-making process in experimental research.’

Choosing an appropriate experimental design is essential because different designs offer varying levels of control, efficiency, and practicality. Understanding their advantages and disadvantages helps researchers match design structure to study goals.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Experimental Designs

Experimental designs provide the framework for how researchers assign treatments, control variability, and measure responses. AP Statistics emphasizes the ability to explain why a specific design is chosen, guided by the research question, available resources, and characteristics of experimental units. Because each design has distinct strengths and limitations, selecting one requires a careful balance between internal validity, practicality, and representativeness.

Completely Randomized Designs

A completely randomized design is one in which experimental units are randomly assigned to treatments with no grouping structure.

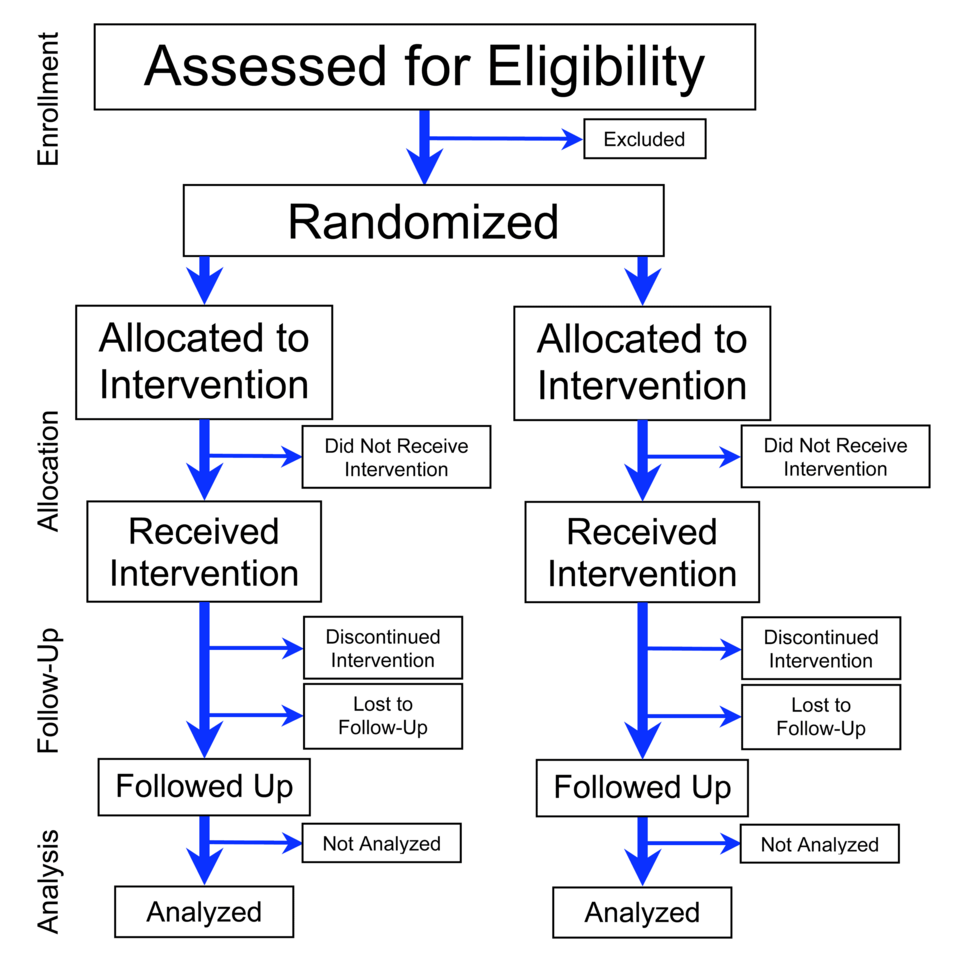

This flowchart illustrates the structure of a parallel randomized trial, showing random assignment, treatment allocation, follow-up, and analysis. It highlights how participants are split into groups through randomization to support unbiased comparisons of treatments. Although created for medical trials, it reflects the principles of completely randomized designs discussed in AP Statistics. Source.

Advantages

Simplicity: Easy to implement and analyze due to straightforward random assignment.

Strong control of confounding: Random assignment, when used correctly, balances both known and unknown sources of variation across treatment groups.

Flexibility: Works well when experimental units are similar enough that blocking or pairing offers little additional benefit.

Disadvantages

Inefficiency with heterogeneous experimental units: When units differ meaningfully, variability within treatment groups increases, reducing the ability to detect treatment effects.

No built-in control for group differences: Cannot account for systematic differences, such as batches, locations, or natural subgroups, without incorporating additional design features.

Randomized Block Designs

A randomized block design groups similar experimental units into blocks, then randomizes treatments within each block. Blocking is used when a variable is expected to influence the response.

Blocking: A design strategy in which experimental units are grouped by a variable expected to affect the response, reducing variability within treatment comparisons.

Researchers use this structure to isolate the effect of the treatment from the effect of the blocking variable.

Advantages

Reduced variability: Blocking decreases within-group variation, making estimates of treatment effects more precise.

Better comparisons: Units in the same block are deliberately similar, improving fairness of treatment comparisons.

Useful for nuisance variables: Blocks help control variables that are not of interest but could affect results.

Disadvantages

Increased complexity: Requires careful identification of a meaningful blocking variable and proper assignment within each block.

Limited applicability: If no clear blocking variable exists, the added structure provides little benefit.

Potential for small block sizes: Some blocks may be too small to allocate treatments efficiently.

A normal sentence is placed here to maintain required spacing before any other block structures.

Matched Pairs Designs

A matched pairs design is a special case of blocking in which each block contains only two units, or where one unit receives both treatments under different conditions.

Advantages

Strong control of confounding: Matching reduces variability by pairing highly similar units or by comparing the same unit to itself.

Increased precision: Differences within pairs isolate treatment effects more effectively than between-subject comparisons.

Ideal for two-treatment studies: Allows very efficient comparisons when only two conditions are tested.

Disadvantages

Limited to two treatments: Does not generalize well to studies with more than two conditions.

Challenging matching process: Requires finding pairs that are meaningfully similar; poor matching reduces benefits.

Carryover effects (in repeated-measures versions): When one unit receives both treatments, treatment order can influence outcomes unless well controlled.

Single-Blind and Double-Blind Designs

Blinding refers to withholding information about treatment assignment from participants, researchers, or both.

Blinding: A method used to prevent subjects, researchers, or both from knowing which treatment is assigned, reducing bias in responses or measurement.

Advantages

Reduces response and measurement bias: Blinding minimizes influence from expectations, beliefs, or researcher behavior.

Improves credibility: Results from blinded experiments are generally considered more reliable.

Disadvantages

Logistical challenges: Some treatments cannot be blinded due to physical characteristics or ethical constraints.

Increased cost and complexity: Maintaining blinding requires additional controls, monitoring, and materials.

Control Groups and the Placebo Effect

A control group provides a baseline for comparison, while the placebo effect refers to changes in subjects’ responses due to expectations rather than the treatment itself.

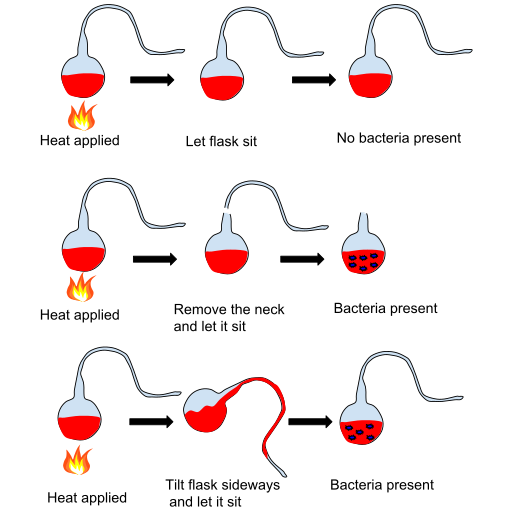

This diagram illustrates Louis Pasteur’s controlled experiment testing microbial growth using flasks with different conditions. One flask’s curved neck functions as a control that prevents contamination, while altered flasks allow bacteria to enter and grow. Although tied to biology, the figure clearly visualizes treatment–control contrasts relevant to experimental design principles. Source.

Advantages

Clear baseline: Control groups help isolate treatment effects.

Reduces confounding: Placebo controls distinguish real treatment effects from psychological responses.

Disadvantages

Ethical constraints: Withholding treatment may be inappropriate in some settings.

Implementation difficulty: Creating believable placebos can be challenging.

Choosing Among Designs

Researchers must weigh advantages and disadvantages based on study needs and constraints. Key factors include:

Nature of the research question

Does the study require two-treatment comparisons, multiple groups, or control of nuisance variables?

Characteristics of experimental units

Are units similar, or is there important variability to control?

Resources and logistics

What materials, time, and personnel are available for managing complex designs?

Validity considerations

How much control is needed to make evidence of causality convincing?

Matching design structure to these considerations ensures alignment with VAR-3.D.1 expectations: selecting the most appropriate experimental design by understanding its strengths, weaknesses, and suitability for the study context.

FAQ

Larger sample sizes make complex designs such as randomised block or matched pairs more feasible because there are enough units to form meaningful groups or pairs.

With very small samples, simpler structures are often preferred because blocking or matching may create groups too small to allocate treatments fairly.

When resources limit sample size, researchers often prioritise designs that maximise precision with minimal units, such as matched pairs for two-treatment comparisons.

Blocking works best when the blocking variable is strongly associated with the response.

To decide whether blocking is worthwhile, researchers consider:

• Whether differences in the blocking variable are large enough to affect outcomes

• Whether the variable can be measured reliably before treatment

• Whether blocks can be formed without causing unbalanced treatment allocations

If these conditions are not met, blocking may add complexity without improving precision.

Matched pairs designs become problematic when matching cannot capture subtle but important differences between units.

If the characteristic used for matching is weakly related to the response, the design offers little advantage.

Matched pairs are also unsuitable when more than two treatments are being compared, as the structure cannot extend naturally to multiple conditions.

Blinding is prioritised when awareness of the treatment could influence behaviour, reporting, or measurement.

Researchers assess:

• Whether participants might consciously or subconsciously alter responses

• Whether researchers collecting data could unintentionally bias results

• Whether the treatment has obvious features that make blinding impossible

If bias risk is low or blinding is impractical, simpler designs without blinding may still be acceptable.

Design choice is rarely made in isolation and often reflects logistical constraints.

Common limiting factors include:

• Cost of implementing multiple treatment conditions

• Availability of experimental units needed for blocking or pairing

• Time required to randomise, monitor, and measure outcomes

• Physical layout limitations, such as field experiments restricted by land structure

These constraints mean the statistically ideal design may not always be the most practical or feasible.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher has a group of 120 experimental units that are all very similar. She wants to compare the effects of two treatments. She is considering using a randomised block design but is unsure whether it is appropriate.

(a) Explain why a completely randomised design may be more suitable in this situation.

(2 marks)

Question 1

(a) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for stating that a completely randomised design is suitable because the experimental units are already similar, so blocking is unnecessary.

• 1 mark for noting that this design is simpler and still effectively controls variability through random assignment.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A scientist is testing three fertiliser types (A, B, and C) on crop growth. The fields used for testing vary substantially in soil quality, and the scientist is concerned that this variability could mask differences between fertilisers.

(a) Identify the experimental design that would best address this concern and justify your choice.

(b) Describe one advantage and one disadvantage of using this design in this context.

(c) Explain how this design improves the reliability of conclusions about differences between fertilisers.

(6 marks)

Question 2

(a) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for correctly identifying a randomised block design.

• 1 mark for justifying that blocks can be formed based on soil quality to control variability.

(b) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for a correct advantage, such as reducing variability due to soil differences.

• 1 mark for a correct disadvantage, such as increased complexity or difficulty forming balanced blocks.

(c) Up to 2 marks:

• 1 mark for explaining that blocking results in fairer comparisons because treatments are applied within similar soil-quality groups.

• 1 mark for linking reduced variability or improved precision to more reliable conclusions about fertiliser effectiveness.