AP Syllabus focus:

‘Essential Knowledge: VAR-3.E.4 discusses the conditions under which the results of an experiment can be generalized to a larger population. This includes the importance of experimental units being representative of the larger group and the role of random selection in enhancing representativeness. Detailed notes will cover how these principles support broader applicability of experimental findings.’

Generalizing experimental results requires understanding how sample selection influences broader claims. These notes explain when causal findings from an experiment may legitimately apply to a larger population.

Understanding Generalizability in Experiments

Generalizing results—also called external validity—refers to applying conclusions drawn from an experimental sample to a wider population. Because experiments focus heavily on establishing cause-and-effect, students must recognize that not every well-designed experiment supports broad population-level claims. A study may show a clear causal relationship within its sample but still fail to generalize if participants do not adequately represent the population of interest. This subsubtopic centers on the conditions, constraints, and design decisions that determine whether generalization is appropriate.

The Concept of Representativeness

A central requirement for generalizing results is that the experimental units (individuals or objects studied) reflect the characteristics of the target population. Representativeness refers to how closely the sample matches the broader group in relevant attributes.

Representativeness: The degree to which the characteristics of the experimental sample mirror those of the larger population of interest.

Representativeness ensures that any treatment effect observed in the experiment is likely to occur similarly across the broader group. If a sample lacks diversity or systematically excludes certain subgroups, conclusions may not hold beyond those actually studied.

Random Selection and Its Role in Generalization

The syllabus emphasizes the importance of random selection, which is the process of choosing experimental units using chance so that each member of the population has an equal opportunity for inclusion. Random selection is distinct from random assignment (used to create comparable treatment groups within an experiment).

Random Selection: A sampling method in which every member of the defined population has an equal chance of being chosen for the sample.

Random selection strengthens external validity by reducing systematic differences between the sample and population.

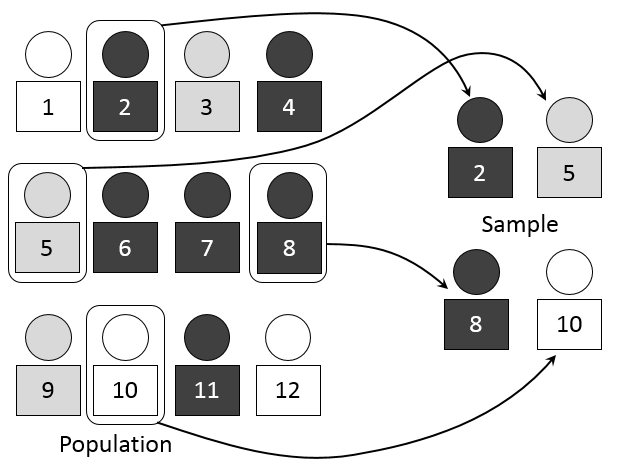

A diagram illustrating a simple random sample drawn from a larger population. Each individual has an equal chance of being selected, reinforcing the connection between random selection, representativeness, and valid generalization to the population. The image focuses specifically on the sampling step and does not depict experimental treatment assignment. Source.

A normal sentence is included here to maintain the required spacing before any subsequent definition or equation block.

Why Random Assignment Alone Does Not Ensure Generalizability

While random assignment creates comparable treatment groups and supports internal validity, it does not guarantee external validity.

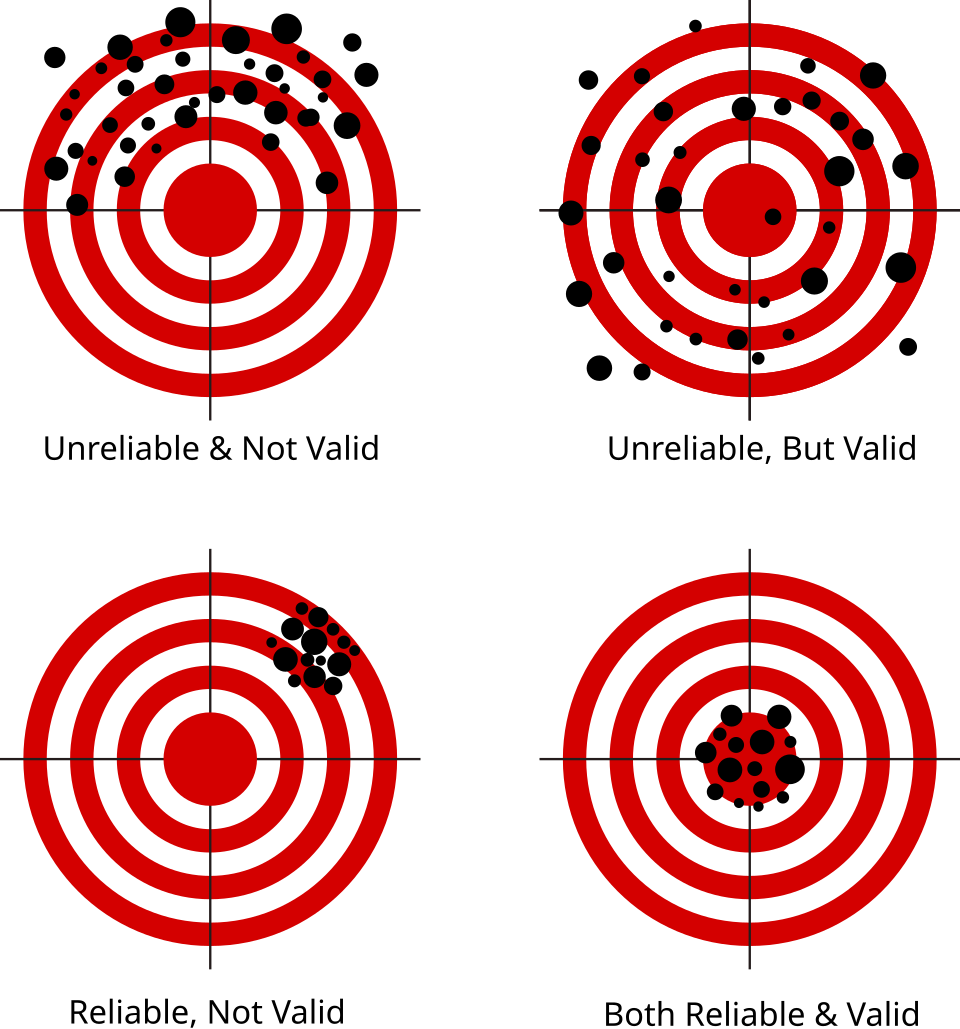

A 2×2 grid of bullseye targets illustrating combinations of reliability and validity. The diagram shows how results can be consistent without being valid, supporting the idea that internal validity alone is insufficient for generalizing experimental findings. The figure also introduces reliability, which extends beyond the specific focus of this subsubtopic but aids conceptual understanding of what it means for results to be valid. Source.

Conditions Required for Generalizing Experimental Results

Generalizing findings responsibly requires meeting certain conditions that align with the syllabus focus. The most important conditions include:

1. Representative Experimental Units

The sample should reflect the target population in characteristics relevant to the response variable. Researchers should consider:

Demographics (age, gender, socioeconomic factors)

Baseline behaviors or conditions associated with the response

Environmental or contextual factors relevant to the treatment

If a particular subgroup dominates the sample, the ability to generalize is weakened.

2. Random Selection from the Population of Interest

Random selection supports generalization because:

It minimizes sampling bias.

It distributes natural variability across the sample.

It allows probability-based inference about the population.

When random selection is absent, researchers must restrict conclusions to the sample studied rather than the broader population.

3. Clearly Defined Population

Generalizability requires a precise definition of the population to which results may apply. Students should recognize that:

The population must be identified before collecting data.

The characteristics used to define the population determine whether the sample is appropriate.

A mismatch between the sample and population definition undermines inference.

4. Sufficient Sample Size

A larger sample increases the likelihood that the chosen units capture the diversity of the population. While size alone cannot fix poor sampling methods, it strengthens generalization when combined with random selection.

5. Consistency of Treatment Conditions

Generalization assumes that the treatment would operate similarly in the population as it did in the experiment. This requires:

A clearly defined treatment

Consistent application of treatment procedures

Consideration of context-dependent effects

If population members would experience the treatment differently, generalization weakens.

Limits on Generalizing Experimental Findings

Even when conditions for generalization are mostly met, students should understand the constraints that may prevent broader application. Limits commonly arise from:

Lack of Random Selection

Experiments using convenience samples

Studies relying on volunteers, club members, or special groups

Samples drawn from a single location or institution

Narrow Experimental Scope

Highly controlled settings that differ from the real world

Treatment levels that do not reflect typical usage

Conditions that cannot be replicated outside the experiment

Ethical or Practical Barriers

Some populations cannot be sampled randomly due to feasibility or ethical constraints, which limits external validity even in well-run experiments.

Strategies to Strengthen Generalizability

To support valid claims about wider populations, researchers may:

Use stratified or multistage sampling when pure random selection is impractical.

Conduct replication studies in different populations or contexts.

Expand inclusion criteria to capture greater diversity.

Compare sample characteristics with known population data.

These practices align with the AP Statistics focus on understanding how representativeness and random selection determine whether causal conclusions extend beyond the experimental units studied.

FAQ

External validity is evaluated by examining whether the sample captures the key sources of variation present in the population. When a population is diverse, representativeness depends on whether important subgroups are proportionally reflected.

Researchers may use stratified sampling to ensure that critical characteristics such as age, region, or experience levels are included.

If major subgroups are missing, generalisation should be limited to the groups actually represented.

Generalisation may be cautiously justified if the sample’s characteristics align closely with known population parameters.

However, this relies on strong evidence that there is no hidden bias in how participants were chosen.

Because non-random sampling always risks systematic differences, any generalisation made should be framed as tentative rather than definitive.

Context can strongly influence treatment effects. Conditions such as setting, delivery method, or environmental constraints may shape how the treatment works.

Generalisation is more appropriate when the context of the experiment matches the context of the target population.

If the treatment’s success depends on highly specific conditions, external validity is weakened.

Researchers may conduct subgroup analyses, comparing treatment effects across categories such as gender, experience level, or training intensity.

They may also assess interaction effects to detect whether the treatment behaves differently for different groups.

If effects vary widely between subgroups, generalisation should be limited to those showing consistent patterns.

Researchers can employ techniques to approximate representativeness, such as:

Recruiting from multiple locations

Ensuring demographic diversity

Matching sample characteristics to population benchmarks

They may also replicate the study across different samples to build accumulated evidence.

Although these approaches cannot replace true random selection, they strengthen confidence when broader generalisation is required.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher conducts an experiment to test whether a new revision technique improves exam performance. The participants are all volunteers from a single school. The school wants to apply the findings to all secondary students nationally.

Explain why the results of this experiment may not be generalisable to the wider population.

(3 marks)

Question 1 (3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for the following points:

1 mark: States that volunteers may not be representative of all secondary students.

1 mark: Identifies that using participants from a single school limits representativeness.

1 mark: Explains that without a representative or randomly selected sample, results cannot be confidently applied to the wider population.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A sports scientist designs an experiment to test whether a new warm-up routine reduces injury rates among athletes. The scientist randomly assigns athletes to two treatment groups but recruits all participants from a single elite training academy.

(a) Explain why random assignment alone is not enough to justify generalising the results to all athletes.

(b) Identify two conditions that would need to be met for the results to be generalisable to the wider population of athletes.

(c) Suggest one change the scientist could make to strengthen the generalisability of the study.

(6 marks)

Question 2 (6 marks)

(a) (2 marks)

1 mark: States that random assignment only creates comparable treatment groups within the sample.

1 mark: States that random assignment does not ensure the sample represents the wider population.

(b) (3 marks)

Award 1 mark for each valid condition, up to 3 marks. Examples include:

The sample must be representative of all athletes.

The sample should come from a randomly selected group of athletes.

The population must be clearly defined to match the sample.

Treatment conditions must reflect realistic conditions across the population.

(c) (1 mark)

1 mark: Suggests a legitimate improvement to increase generalisability, such as recruiting athletes from multiple clubs, using random selection, or diversifying the athlete sample.