AP Syllabus focus:

‘UNC-3.E & UNC-3.E.2: Describe the geometric probability function and how to calculate the probability that the first success occurs on the xth trial, with the formula P(X=x) = p(1-p)^(x-1) for x=1,2,3,... This involves detailing the steps for applying the formula to specific problems, highlighting the exponential decay characteristic of the geometric distribution.’

Geometric probabilities describe how likely it is that the first success in a repeated chance process occurs on a specific trial, forming a crucial bridge between randomness and quantifiable patterns.

Understanding the Purpose of Geometric Probabilities

Geometric probabilities arise when analyzing repeated independent Bernoulli trials, in which each trial has exactly two possible outcomes—success or failure—and the probability of success remains constant across trials. Students must understand that the central question in this subsubtopic focuses on determining the probability that the first success occurs on a particular trial number. This emphasis distinguishes geometric distributions from the binomial distribution, which instead counts the number of successes in a fixed number of trials.

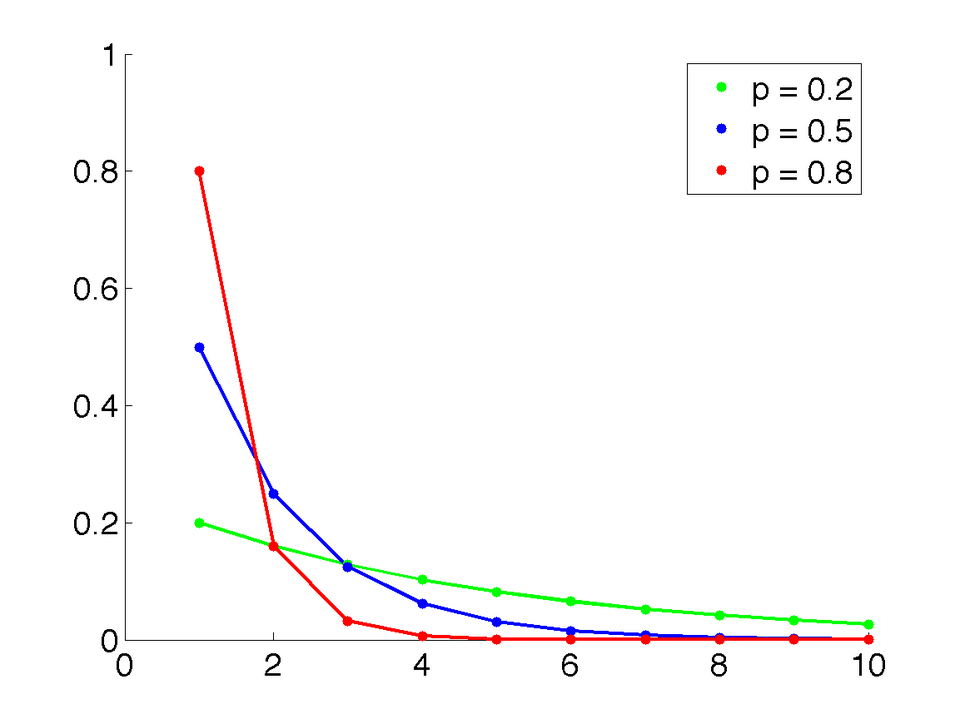

Probability mass function of a geometric distribution with support starting at 1. The bar heights represent the likelihood of the first success on each trial, decreasing steadily to illustrate exponential decay. The image directly corresponds to the AP formula and includes no additional concepts. Source.

When working with geometric distributions, the key conceptual idea is that earlier failures accumulate until the first success finally occurs. This cumulative structure produces the classical decreasing pattern known as exponential decay, where probabilities become progressively smaller as the required trial count increases.

Components of the Geometric Probability Function

The geometric probability function captures the chance that the first success appears on trial x, where x must be a positive integer. This structure reflects the requirement that outcomes are counted by the number of trials needed to achieve success, and not by the total number of successes across several trials.

Before introducing the formula, it is essential to clarify two foundational terms used throughout geometric probability reasoning.

Success Probability (p): The fixed probability that a single trial results in a success.

A single sentence ensures conceptual continuity before introducing the second term.

Failure Probability (1 − p): The probability that a single trial results in a failure, calculated as one minus the probability of success.

These terms frame the geometric setting by establishing how each trial behaves. In particular, the insistence on fixed probabilities ensures that each trial is statistically identical, satisfying a key requirement for geometric modeling.

The Geometric Probability Formula

The probability that the first success occurs on the xth trial depends on observing failures on all previous trials and a success on the final one. Because geometric trials are independent, the probability of this combined sequence can be expressed as a product of probabilities.

EQUATION

= Probability of success on any single trial

= Probability of failure on any single trial

= Trial number on which the first success occurs (x = 1, 2, 3, …)

A brief sentence here allows conceptual reinforcement and avoids placing equation blocks back-to-back. This formula provides a structured method for determining how likely it is that a process requiring repeated attempts will achieve success at a specified point in time.

Interpreting the Structure of Geometric Probabilities

The geometric function highlights that as the required number of trials increases, the probability of the first success occurring on that later trial becomes smaller. This decrease is a direct result of multiplying additional failure probabilities for each preceding trial. Thus, the geometric model embodies an important real-world insight: the more consecutive failures observed, the less likely it becomes that the first success will occur far into the sequence.

Key structural features include:

Independence of trials, ensuring that the outcome of one trial does not influence any other.

Consistent success probability, which must remain unchanged across all attempts.

Sequential failure requirement, where each failure contributes multiplicatively to the probability calculation.

Final success condition, closing the sequence and determining the specific value of the variable x.

Applying the Formula in Geometric Contexts

Although worked examples are excluded here, it is essential for students to understand the general process followed when applying geometric probabilities:

Identify p, the probability of success in a single trial.

Recognize that x represents the exact trial of the first success, not the total number of successes.

Determine that the probability structure follows the pattern of earlier failures followed by success.

Substitute values into the geometric probability formula.

Interpret the resulting probability in terms of likelihood across repeated attempts.

The geometric model applies to a wide range of situations involving waiting times for the first occurrence of an event—such as the first defective item, the first correct guess, or the first time a condition is met—provided that the conditions of independence and constant success probability hold.

Why the Distribution Exhibits Exponential Decay

The characteristic exponential decay of geometric distributions emerges from the repeated multiplication of the failure probability . Each additional trial requiring failure adds one more factor of , diminishing the probability systematically. This decay pattern is fundamental to the geometric model and reflects how real-world processes lose likelihood over extended sequences of failed attempts.

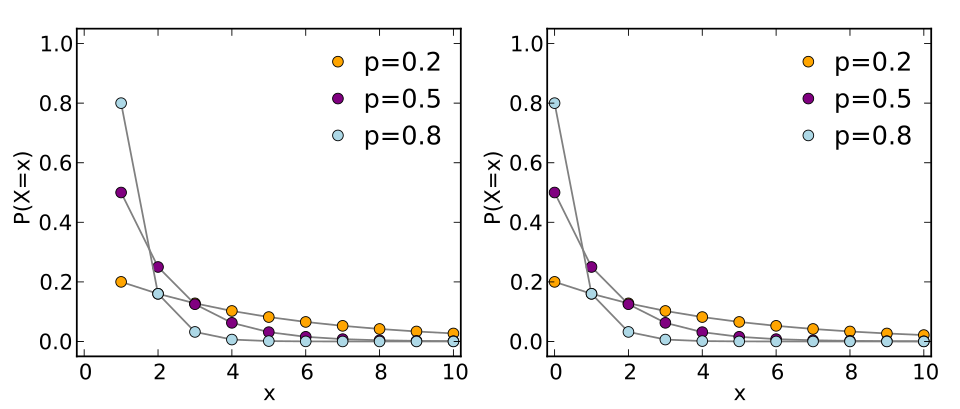

Probability mass functions for geometric distributions with varying success probabilities. Larger values of p produce steeper decay, illustrating how the first-success probability declines over longer sequences of failures. The right panel includes an alternative parameterization, which is conceptually related but beyond the AP requirement. Source.

In AP Statistics, understanding this decay not only supports mastery of the geometric formula but also deepens students’ intuition about random processes that involve waiting for a first occurrence.

FAQ

The decreasing probability reflects the growing sequence of failures required before achieving the first success. Each extra trial adds another layer of “no success yet,” making that specific outcome less likely.

This behaviour is a defining feature of geometric distributions and helps explain why waiting-time models often taper off quickly in likelihood as time increases.

Yes, geometric models are particularly well suited to rare-event scenarios. A small probability of success simply means that higher trial numbers retain non-negligible probabilities compared with situations where success is common.

However, the distribution will still decay; it will simply do so more slowly, resulting in a longer right tail.

A higher success probability produces a steeper decline because success is likely early, concentrating probability mass near the first few trials.

A lower success probability flattens the decay, spreading probability mass across more trial numbers and creating a longer tail.

Independence ensures that the chance of success remains unaffected by previous outcomes. Without independence:

The probability of success may shift over time.

The waiting-time interpretation breaks down.

The geometric formula no longer reflects the true sequence probability.

Thus, independence preserves the model’s structural integrity.

Not directly. The geometric distribution applies only to discrete counts of attempts or steps.

In continuous time, an analogous waiting-time model would typically use an exponential distribution, which represents time rather than trial count. While conceptually similar, it operates under a different mathematical framework.

Practice Questions

A basketball player has a constant probability of 0.25 of making a free throw on any attempt. Assuming each attempt is independent, what is the probability that the player makes their first successful free throw on their third attempt?

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• Correct recognition that the probability of first success on the third attempt is calculated using p(1 − p)^(x − 1). (1 mark)

• Substitution: p = 0.25, x = 3 giving 0.25 × (0.75)^2. (1 mark)

• Correct final probability: 0.140625 (or equivalent). (1 mark)

Total: 3 marks

A wildlife researcher is studying a rare species of bird. Each hour, there is a constant probability of 0.12 that at least one bird will be sighted, and sightings in different hours are independent.

(a) Explain why the number of hours until the first sighting can be modelled using a geometric distribution.

(b) Calculate the probability that the first sighting occurs in the fifth hour.

(c) Describe how the probability of a first sighting changes as the number of hours increases, and explain why.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• States that each hour has two outcomes (sighting or no sighting) with constant probability. (1 mark)

• States that hours are independent. (1 mark)

• Concludes that these conditions align with those of a geometric distribution. (1 mark)

(b)

• Uses geometric probability structure p(1 − p)^(x − 1). (1 mark)

• Correct substitution: 0.12 × (0.88)^4. (1 mark)

• Correct final probability: 0.12 × 0.5997... ≈ 0.07196 (allow rounding). (1 mark)

(c)

• States that probabilities decrease as the number of hours increases. (1 mark)

• Explains that this occurs because each additional hour requires another failure (no sighting) multiplied into the probability. (1 mark)

Total: 6 marks