AP Syllabus focus:

‘Learning Objective VAR-5.C: Explain the concept of mean or expected value for a discrete random variable X, represented as μX = Σ[xi * P(xi)], where xi are the values of X and P(xi) their respective probabilities (VAR-5.C.2). Illustrate how to calculate this using given values.’

The mean of a discrete random variable provides a numerical summary of long-run outcomes, allowing statisticians to quantify expected behavior when chance governs individual observations.

Understanding the Mean of a Discrete Random Variable

The mean of a discrete random variable is one of the most essential parameters in probability, reflecting the long-run average value expected if a random process were repeated indefinitely. In AP Statistics, this concept is central because it links probability models to real-world interpretation, enabling students to describe typical outcomes even when individual results vary due to randomness.

A discrete random variable is a variable whose possible values form a countable set, such as whole numbers associated with random outcomes. Because these values occur with different likelihoods, the mean must account for both the magnitude of the values and the probabilities with which they occur.

Discrete Random Variable: A random variable that can assume only a countable number of distinct numerical values, each associated with a probability.

The mean of a discrete random variable is also called its expected value, emphasizing that the measure represents a theoretical long-term average rather than a prediction for any single trial. Although individual outcomes vary, the expected value provides a stable benchmark for describing the distribution’s center.

The Structure of Expected Value

To compute the mean, each possible value of the random variable is weighted by its probability.

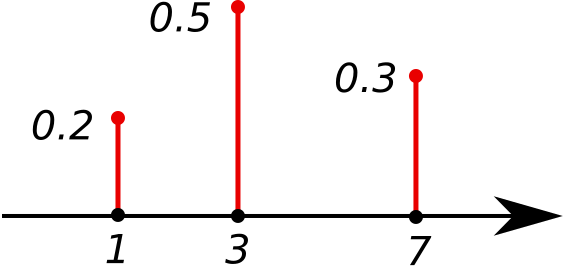

A probability mass function illustrating three possible values of a discrete random variable, with bar heights showing the probability of each outcome. The diagram highlights how each value contributes differently to the mean because of its associated probability. This supports understanding of the expected value as a weighted average. Source.

This mirrors the idea of a weighted average, where more likely outcomes contribute more heavily to the final value. This process formally defines how probabilities shape the overall behavior of the random variable.

EQUATION

= A possible value of the discrete random variable

= Probability associated with value $x_

Because probabilities must sum to 1, this formula ensures that every possible outcome contributes proportionally to the mean based on its chance of occurring.

After applying this computation, the resulting value is interpreted within the context of the original scenario. While the expected value may not correspond to a possible single outcome, it effectively describes the distribution’s long-term average.

Why Expected Value Is Meaningful

The mean of a discrete random variable is valuable because it reflects the center of its probability distribution. It functions as a balancing point: outcomes larger than the mean are offset by outcomes smaller than the mean when each is weighted by probability.

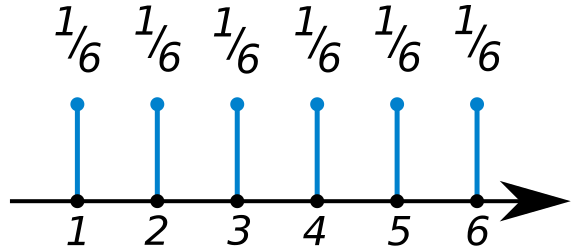

This connects to the broader concept of long-run relative frequency. Over many repetitions of a random process, the average of observed outcomes tends to stabilize near the expected value, illustrating the conceptual bridge between probability theory and empirical behavior.

Over a large number of trials, the average of observed values will tend to move closer to the mean of the underlying random variable.

A probability mass function for a fair six-sided die, showing each outcome with probability 1/6. The uniform bars highlight how each value contributes equally to the expected value. This illustrates the idea that the long-run average of many rolls converges toward the mean. Source.

Key points about the interpretation of expected value include:

It describes the theoretical average outcome of infinitely many trials.

It may not represent a physically achievable result in a single trial.

It provides a basis for comparing different probabilistic scenarios.

It supports decision-making in contexts such as risk assessment and resource allocation.

These principles make the expected value indispensable in probability modeling and statistical reasoning.

Steps in Computing the Mean

To support conceptual understanding, it is helpful to outline the logical procedure used to calculate the mean of a discrete random variable:

Identify the random variable and ensure its values are discrete and countable.

List all possible values the random variable can take.

Determine each probability, ensuring that all probabilities sum to 1.

Multiply each value by its corresponding probability to weight contributions appropriately.

Sum all weighted products, yielding the mean or expected value.

These steps illustrate how probability distributions directly inform the calculation, reinforcing the link between a distribution’s structure and its expected behavior.

Significance of the Mean in Probability Models

Understanding how to calculate the mean equips students to engage with broader statistical analyses, particularly those involving prediction or characterization of populations. The expected value becomes a foundation for studying additional parameters—such as variance and standard deviation—that describe variability around the mean.

In applications, the mean supports interpretations such as:

Anticipated average outcomes for repeated random processes.

Comparisons between different probability models or scenarios.

Evaluations of fairness or efficiency in systems governed by chance.

Communication of long-term expectations in real-world contexts.

Recognizing how the expected value is constructed promotes a deeper understanding of how probability distributions summarize complex random behavior.

FAQ

The mean of a discrete random variable is a weighted average, in which each value contributes according to its probability rather than being treated equally.

It reflects the long-run average outcome of a random process, whereas a simple arithmetic mean only summarises a given data set.

If the probabilities are all equal, the two means coincide, but this is uncommon in genuine probability models.

Yes. The expected value often falls between possible outcomes because it is a theoretical long-run average rather than a single attainable result.

For example, even if a variable only takes whole numbers, its mean may be non-integer.

This does not reduce its usefulness: it still describes the centre of the probability distribution.

Scaling the probabilities does not change the mean, as long as the probabilities remain proportional and sum back to 1.

This is because the expected value depends on the relative, not absolute, weight given to each outcome.

No. The mean depends only on outcomes and their associated probabilities, not how they are listed or organised.

Changing the order of values or probabilities is purely cosmetic and leaves the expected value unchanged.

The mean can be significantly affected if a high-magnitude value, even with small probability, is altered.

This is because the expected value multiplies each value by its probability, so:

• Small changes to very large outcomes can shift the mean noticeably.

• Small changes to small outcomes usually have little effect.

This sensitivity is one reason why expected value is informative but not sufficient on its own to describe a distribution.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A discrete random variable X takes the values 1, 4, and 8 with probabilities 0.5, 0.2, and 0.3 respectively.

Calculate the mean (expected value) of X.

Question 1 (3 marks total)

• 1 mark: Correctly multiplying each value by its probability (1×0.5, 4×0.2, 8×0.3).

• 1 mark: Correctly summing the products.

• 1 mark: Stating the correct mean of X (3.9).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A company records the number of customer enquiries received per hour. The discrete random variable N represents the number of enquiries in a randomly selected hour. The possible values of N are 0, 1, 3, and 6, with associated probabilities 0.1, 0.4, p, and 0.2 respectively.

(a) Show that p must be 0.3.

(b) Calculate the mean (expected value) of N.

(c) Explain what this mean represents in the context of the company’s records.

Question 2 (6 marks total)

(a) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Using the condition that probabilities must sum to 1: 0.1 + 0.4 + p + 0.2 = 1.

• 1 mark: Solving to obtain p = 0.3.

(b) (3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly multiplying each value by its probability.

• 1 mark: Summing all weighted values.

• 1 mark: Giving the correct mean of N (2.2).

(c) (1 mark)

• 1 mark: Correct contextual interpretation, e.g. “On average, the company can expect about 2.2 customer enquiries per hour over the long run,” or equivalent wording.