AP Syllabus focus:

‘Popular sovereignty means government power comes from the consent of the people; legitimate authority rests on the governed and is expressed through participation and elections.’

Popular sovereignty is a foundational democratic ideal in the United States, explaining why government is considered legitimate only when the public authorises it. This page focuses on consent, and how it is expressed through participation and elections.

Core idea: power originates with the people

Popular sovereignty holds that the public is the ultimate source of political authority. Government officials do not “own” power; they exercise delegated power that can be renewed, limited, or withdrawn by the people.

Popular sovereignty: The principle that governmental power originates with the people, who authorise leaders and laws through democratic participation and elections.

A central implication is legitimacy: the belief that a government’s authority is rightful and should be obeyed. In this model, legitimacy depends on continuing public authorisation rather than force.

Consent of the governed

Consent of the governed is the public’s acceptance of government authority and decisions. In practice, consent is not one-time; it is ongoing and must be reaffirmed through regular opportunities for political participation.

How consent is expressed

The syllabus emphasises that legitimate authority “is expressed through participation and elections.” Key expressions include:

Elections as authorisation and accountability

Elections are the most formal mechanism for translating popular will into government action.

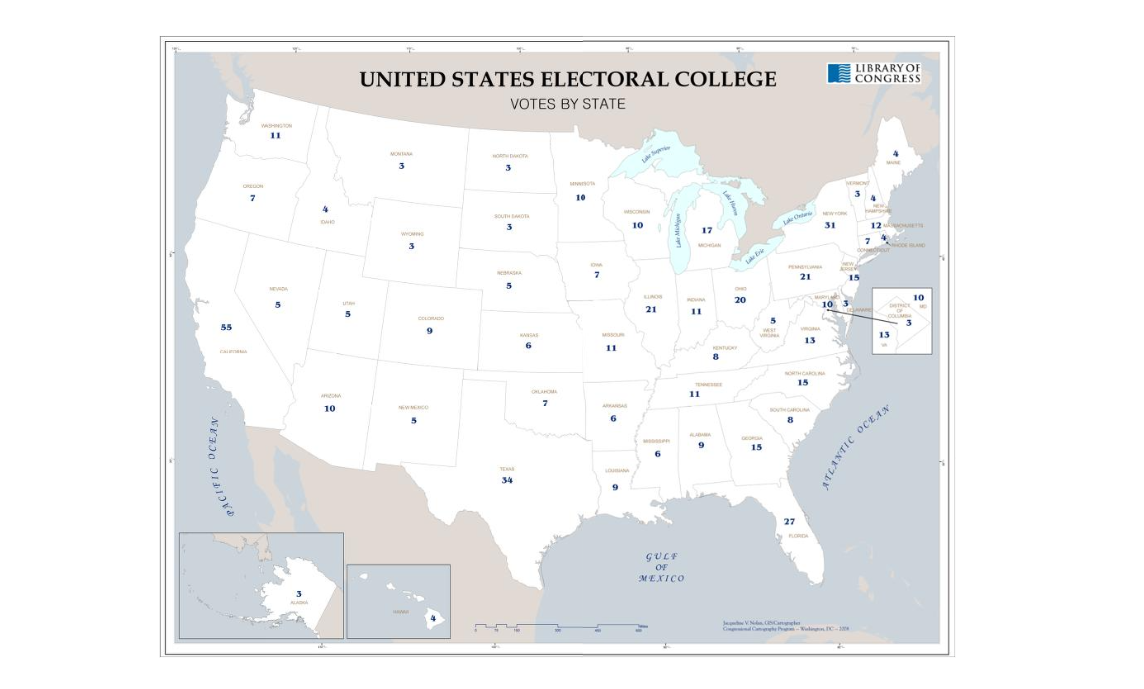

This diagrammatic explanation of the Electoral College process shows how individual ballots are aggregated at the state level, translated into electoral votes, and then formally counted by Congress. It clarifies how presidential elections institutionalize popular participation while also illustrating that the mechanism for selecting executives can be indirect even when legitimacy is grounded in public authorization. Source

Selecting leaders: Voters choose officeholders who claim a mandate to govern.

Policy direction: Campaigns and party platforms connect public preferences to governing agendas.

Accountability: Officials can be retained or replaced, reinforcing that authority depends on the governed.

When elections are competitive and recurring, they serve as a continual “consent check” on those in power.

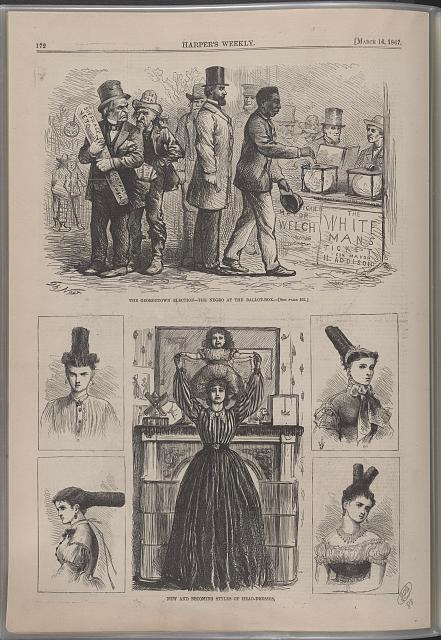

Thomas Nast’s 1867 wood engraving depicts an African American voter casting a ballot at a polling place, with the competing ballot boxes explicitly labeled. As a primary source from the Reconstruction era, it highlights how access to the vote has been central to the practical meaning of “consent of the governed,” and how debates over suffrage shape who is included in popular sovereignty. Source

Participation beyond voting

Participation broadens how consent is communicated and contested between elections.

Political speech and debate: Public discussion shapes what governing actions are seen as acceptable.

Civic engagement: Attending meetings, contacting officials, and community involvement signal priorities.

Collective action: Peaceful demonstrations and petitioning can indicate approval, dissatisfaction, or demands for change.

These activities matter because they help define whether government actions align with what the governed will tolerate or support.

What “consent” means in real political life

Consent is rarely unanimous, so democratic systems treat it as:

Majority-based but conditional: Winners gain authority, while minorities retain the right to oppose and organise.

Procedural: Consent is often inferred when people participate in, and accept the outcomes of, established democratic processes.

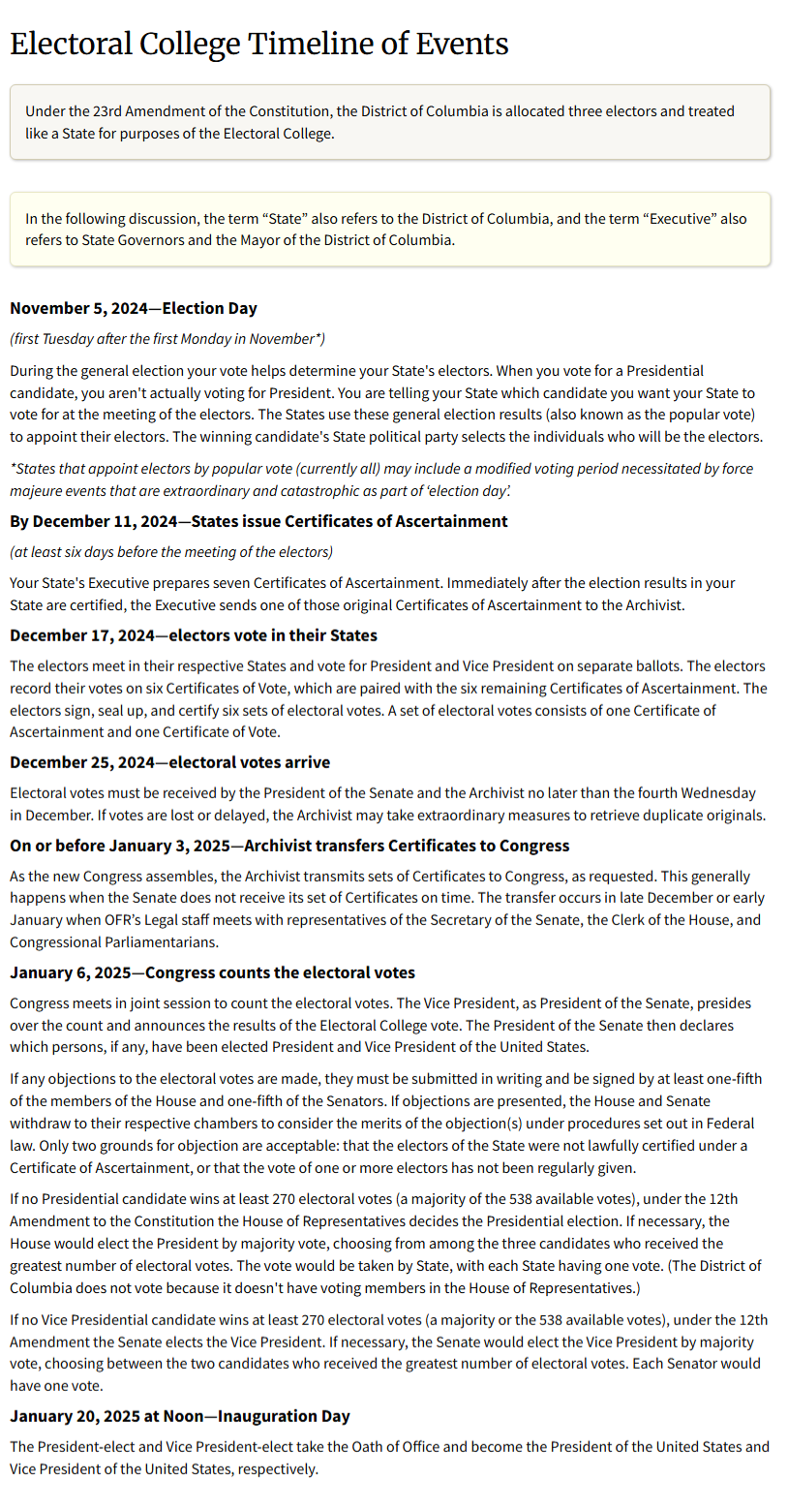

The National Archives’ Electoral College timeline lays out the legally defined sequence from Election Day through the meeting of electors and the congressional count. By visualizing the procedural chain between citizen voting and the final certification of winners, it illustrates how democratic legitimacy is produced through standardized, publicly knowable steps. Source

Revisable: Public approval can shift quickly, and democratic legitimacy requires channels for peaceful change.

Limits and tensions

Popular sovereignty is an ideal, but its practical expression can be weakened when:

Participation is unequal: Barriers to voting or engagement can make “consent” less representative.

Information is distorted: Misleading narratives can undermine meaningful authorisation.

Low trust reduces legitimacy: If many believe institutions ignore the public, consent may appear hollow even if elections occur.

These tensions help explain why democratic legitimacy depends not only on holding elections, but on whether participation is genuinely open and responsive.

FAQ

No. Consent in a democracy is typically procedural and collective rather than unanimous.

It usually means acceptance of a system where decisions are made through agreed rules, even when individuals disagree with outcomes.

Consent can be treated as implied when individuals continue to live under a system and use its institutions, but this is contested.

Non-voting can also signal disengagement or dissatisfaction, making claims of consent less persuasive.

Yes, democratic consent is designed to be revisable.

Common peaceful routes include:

voting incumbents out

sustained advocacy and public pressure

organising to change leadership or priorities within parties

Not automatically, but it can weaken perceived legitimacy.

Low turnout may suggest:

barriers to participation

apathy or disillusionment

weak competition, reducing the sense of meaningful choice

Trust is not identical to consent, but it affects whether authority is viewed as rightful.

When trust declines, people may still obey laws yet doubt that leaders truly represent the governed, reducing the felt legitimacy of decisions.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define popular sovereignty and describe one way consent of the governed is expressed in the United States.

1 mark: Correct definition of popular sovereignty (power originates with the people).

1 mark: One accurate method of expressing consent (e.g., voting in elections, political participation).

(6 marks) Explain how participation and elections contribute to legitimate authority under the principle of consent of the governed. In your answer, include two distinct ways consent is communicated and one reason legitimacy may be questioned even when elections occur.

2 marks: Clear explanation linking elections to legitimacy (authorisation/mandate and accountability).

2 marks: Clear explanation linking participation beyond voting to legitimacy (ongoing signalling, contestation, responsiveness).

1 mark: Identifies a distinct communication of consent (e.g., voting; contacting representatives; peaceful protest).

1 mark: One reason legitimacy may be questioned despite elections (e.g., unequal participation, low trust, misinformation).