AP Syllabus focus:

'National policymaking is constrained because concurrent powers are shared with state governments; this requires negotiation, coordination, and compromise across levels.’

Concurrent powers create a shared governing arena where national goals often depend on state cooperation. Because authority overlaps, federal policymakers must consider state preferences, capacities, and political incentives when designing and implementing policy.

Core idea: shared authority limits unilateral federal action

Concurrent powers and the “shared space”

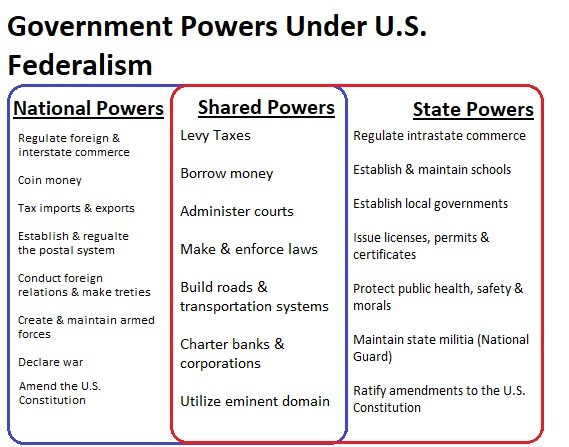

Concurrent powers: powers exercised by both the national and state governments, creating overlapping authority in major policy areas.

A Venn diagram showing the division of governmental authority into federal powers, state powers, and the shared middle area of concurrent powers. The overlap helps explain why many policy areas require joint action: the national government can set goals, but states often retain important tools that shape implementation. Source

In practice, shared authority means the national government cannot simply “command results” in many domestic policy areas. Even when Congress acts, states may control key levers such as day-to-day administration, enforcement priorities, and regulatory details. This turns national policymaking into a multi-level process rather than a single national decision.

Why overlap constrains national policymaking

National initiatives face constraints that are simultaneously constitutional and practical:

Policy design constraints: federal rules must be written to operate alongside existing state laws and agencies.

Political constraints: state officials (governors, attorneys general, legislatures) can support, resist, or reshape implementation.

Administrative constraints: states vary in staffing, expertise, and infrastructure, affecting how uniformly policy can be applied.

Timing constraints: coordinating multiple jurisdictions slows rollout, rulemaking, and enforcement.

How shared powers force negotiation, coordination, and compromise

Negotiation: getting states to cooperate

Because states are not merely “local offices” of the national government, federal policymakers often negotiate to secure cooperation and reduce conflict. Negotiation shows up when national officials:

Draft policies with flexible standards so states can fit rules to local conditions.

Build state input into regulations (consultation, comment periods, state-led planning requirements).

Decide whether to allow state variation or pursue uniformity that may trigger resistance.

Anticipate legal and political pushback from states that view national action as intrusive or costly.

This negotiation is a direct consequence of shared authority: states remain legitimate policymakers in the same issue areas, so they can demand a seat at the table.

Coordination: aligning implementation across levels

Intergovernmental coordination: ongoing cooperation among national, state, and local actors to align rules, administration, and enforcement across levels of government.

Coordination is required because concurrent powers create interdependence.

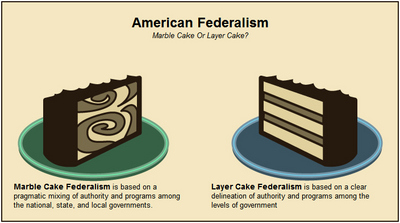

A side-by-side diagram contrasting “layer cake” federalism (clear separation of responsibilities) with “marble cake” federalism (intermixed responsibilities across levels). The marble-cake model provides a visual rationale for why coordination problems arise: when roles are blended, policy success depends on alignment among national, state, and local actors. Source

Even with a clear federal objective, implementation may depend on state agencies and state legal systems. Coordination commonly involves:

Standard-setting vs. administration: federal policy may set goals while states administer programmes.

Information sharing: collecting comparable data across states to monitor compliance and outcomes.

Enforcement alignment: deciding who inspects, investigates, and penalises violations, and how enforcement priorities are set.

Capacity management: addressing uneven state resources that produce uneven compliance and uneven results.

When coordination fails, national policy can become fragmented, with different practical meanings across states.

Compromise: trading uniformity for feasibility

To make policies workable in a shared-power system, national policymakers frequently compromise, which can dilute or reshape original national goals. Common forms include:

Phased implementation to give states time to build capacity.

State flexibility in meeting federal benchmarks, producing variation in methods and outcomes.

Waivers or tailored rules that accommodate state differences but reduce uniform national standards.

Shared responsibility narratives that distribute credit and blame across levels, affecting accountability.

These compromises reflect the central syllabus point: concurrent powers constrain national policymaking by requiring negotiation, coordination, and compromise across levels.

What to know for AP analysis

How to identify a concurrent-power constraint in a scenario

Look for evidence that national action depends on, or is altered by, state involvement:

Federal policy needs state administration or state enforcement to function.

States can influence outcomes through implementation choices and regulatory detail.

National officials adjust policy to avoid state resistance or noncooperation.

Outcomes vary because states differ in capacity and political priorities.

FAQ

States may inspect less, prosecute fewer violations, or focus on different targets.

This can preserve formal federal rules while producing different on-the-ground outcomes across states.

Administrative capacity is the staffing, expertise, systems, and funding to run and enforce policy.

Low-capacity states may implement more slowly or less consistently, limiting national uniformity.

When outcomes vary, officials can shift blame across levels (“the state mismanaged” vs “federal rules were unrealistic”).

Shared responsibility makes it harder for voters to identify who caused success or failure.

Common features include:

flexible benchmarks

phased timelines

optional pathways to compliance

state-specific tailoring mechanisms

One state’s choices can affect neighbours (cross-border movement, markets, or compliance behaviour).

This raises pressure for coordination, but states may still resist uniform approaches that reduce local control.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (3 marks) Explain one way that concurrent powers constrain national policymaking.

1 mark: Identifies a correct constraint linked to shared national–state authority (e.g., need for state cooperation in administration/enforcement).

1 mark: Explains how this creates negotiation, coordination, or compromise.

1 mark: Develops with a clear description of the effect on policy (e.g., slower implementation, variation across states, diluted standards).

Question 2 (6 marks) Analyse how shared national and state authority in an area of concurrent powers can lead to both coordination problems and policy compromise during implementation.

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes concurrent powers as overlapping authority.

2 marks: Coordination problems explained (any two well-developed points: uneven state capacity, inconsistent enforcement, data incompatibility, timing delays, administrative complexity).

2 marks: Policy compromise explained (any two well-developed points: flexibility/variation, phased rollout, waivers/tailoring, weakened uniformity to gain state cooperation).

1 mark: Links explicitly to the idea that national policymaking is constrained because it requires negotiation/coordination/compromise across levels.