AP Syllabus focus:

‘Because power is shared, policy outcomes often depend on intergovernmental bargaining and implementation choices by states within areas of shared or overlapping authority.’

Intergovernmental bargaining explains why federal policy rarely looks identical across the country. Shared authority forces national, state, and local officials to negotiate goals, money, timelines, and enforcement, shaping what policies become in practice.

Core concept: bargaining in a shared-power system

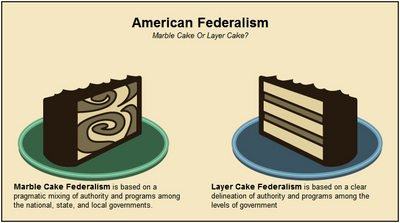

Dual (layer-cake) vs cooperative (marble-cake) federalism diagram. The visual contrast clarifies the structural reason bargaining is so common: in cooperative federalism, responsibilities are intentionally interwoven across levels of government rather than separated into clean jurisdictional layers. That overlap makes implementation details—standards, funding rules, and administrative discretion—central to what policy becomes in practice. Source

Intergovernmental bargaining: Negotiation among national, state, and local governments over policy design, funding, administration, and enforcement, especially where constitutional and statutory responsibilities overlap.

Bargaining is not just “politics”; it is built into policymaking whenever multiple levels of government must cooperate to produce results.

Where bargaining shows up most

Policy design: setting standards, eligibility rules, enforcement mechanisms, and timelines

Administration: who runs programs (state agencies, local governments, contractors), and with what discretion

Funding: how much money is provided, what conditions attach, and what happens if conditions are not met

Enforcement and oversight: reporting requirements, audits, penalties, and corrective plans

Why bargaining shapes policy outcomes

Intergovernmental bargaining matters because states are often key implementers, even when Congress sets the broad policy. Implementation choices can widen or narrow a program’s reach, alter who benefits, and determine compliance.

Key reasons outcomes depend on state choices

Administrative capacity varies: staffing, expertise, technology, and local knowledge affect performance

Political priorities differ: governors, legislatures, and agencies may support, resist, or reframe federal goals

Fiscal conditions differ: balanced-budget rules and revenue bases shape what states can sustain

Legal and institutional differences: state statutes, regulatory procedures, and courts influence rollout

Common bargaining tools and leverage points

National government leverage

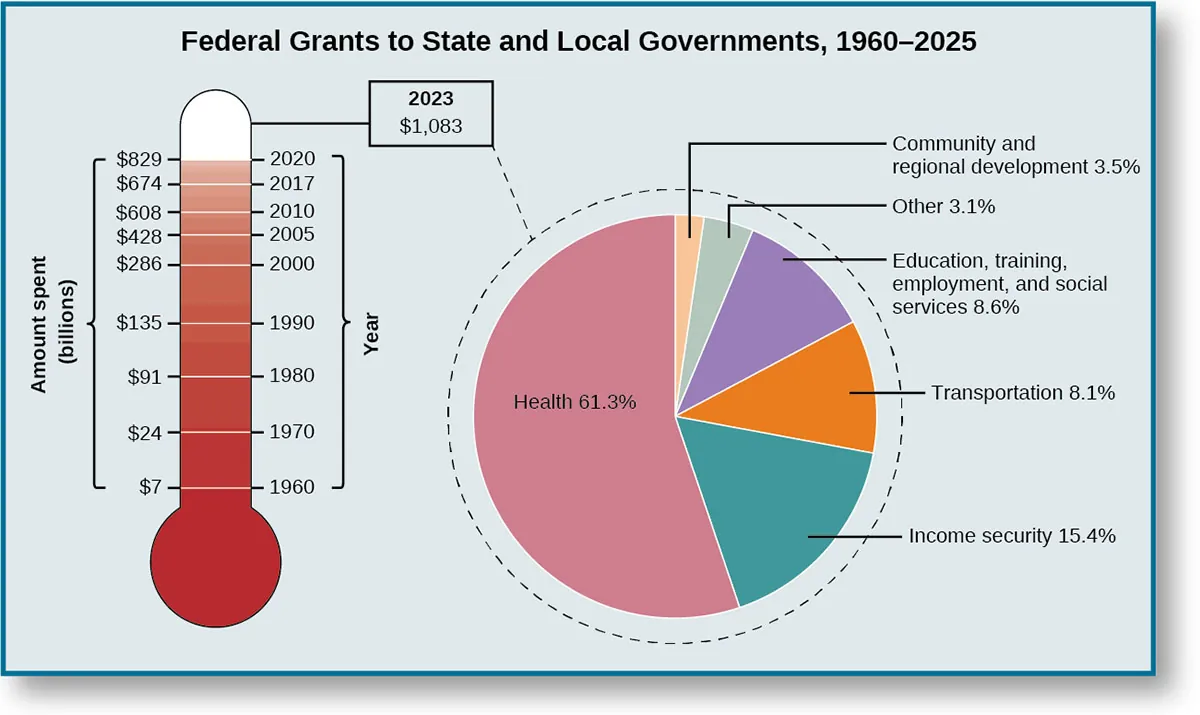

Federal grants to state and local governments over time (thermometer) and by category (pie chart). The graphic shows the long-run growth in federal grants and highlights that a large share of grant dollars flow through major policy areas (especially health), where states typically administer programs under federal rules. This is a concrete illustration of how funding streams create bargaining leverage through conditions, reporting, and oversight. Source

Funding conditions: money offered in exchange for meeting standards or reporting requirements

Deadlines and benchmarks: phased compliance schedules that pressure states to act

Oversight powers: audits, investigations, and withholding funds for noncompliance

Preemption threats: replacing state rules with federal rules when uniformity is prioritised

Waivers and flexibility deals: trading state innovation or political buy-in for measurable results

State and local government leverage

Implementation discretion: choices about enforcement intensity, staffing, and program design within federal boundaries

Collective pressure: multistate coalitions lobbying Congress or agencies for flexibility or more funding

Litigation and legal interpretation: challenging federal requirements or arguing limits on federal power

Information advantage: on-the-ground data used to negotiate timelines, exemptions, or rule adjustments

Partial compliance strategies: meeting minimum requirements while pursuing different policy priorities

Bargaining patterns that change real-world results

Cooperative bargaining (alignment and shared goals)

States may accept federal standards in exchange for resources and flexibility, producing relatively uniform outcomes.

National agencies may reward strong performers with greater discretion and faster approvals.

Conflict bargaining (misalignment and resistance)

States may delay, narrow, or challenge implementation, producing uneven coverage across states.

National officials may respond with stricter oversight, reduced flexibility, or alternative delivery routes.

Strategic bargaining (trade-offs and side payments)

Deals often involve trade-offs: states accept stricter reporting for more autonomy, or accept standards for higher funding.

Implementation rules can become the “real policy,” as agencies negotiate details after legislation passes.

How bargaining translates into policy outcomes

Variation across states

Because bargaining and implementation choices differ, outcomes often diverge in:

Access: who qualifies and how easily they can participate

Benefits and services: scope, quality, and geographic availability

Enforcement: how strictly rules are applied and how violations are handled

Equity: whether similarly situated residents receive similar treatment nationwide

Feedback effects on future policy

Implementation outcomes become evidence used in later bargaining:

Successes can justify expansion or new funding.

Failures can prompt tightened federal standards, new oversight, or redesigned programs.

State innovations can be adopted elsewhere, reshaping national expectations and bargaining baselines.

What to track when analysing intergovernmental outcomes

Who controls administration (state agency vs local delivery vs shared governance)

What discretion exists (rulemaking latitude, enforcement choices, waiver authority)

What incentives/penalties apply (money, deadlines, oversight, reputational pressures)

Whether outcomes are uniform or patchwork, and which bargaining choices produced that pattern

FAQ

Agencies write regulations, approve plans, and interpret compliance.

They can also:

grant or deny waivers

set reporting metrics

prioritise enforcement, which changes states’ negotiating positions

Capacity and alternatives matter.

Stronger positions often come from:

administrative expertise and data

a large affected population (national political salience)

multistate coordination

budget flexibility to refuse or delay participation

Small administrative choices compound.

Differences in:

eligibility verification

outreach and application procedures

enforcement intensity

contracting and local delivery can substantially change who benefits and how effectively.

Aligned partisan control can reduce conflict and speed agreement.

Divided control often increases:

demands for flexibility

oversight disputes

symbolic resistance that still alters implementation details

Litigation can pause implementation, raise uncertainty, and pressure negotiation.

Even without a final victory, lawsuits can produce:

settlements

narrowed enforcement

revised regulations that reflect state preferences

Practice Questions

Define intergovernmental bargaining and identify one way it can influence policy outcomes. (2 marks)

1 mark: Accurate definition of intergovernmental bargaining (negotiation among levels of government over policy design/funding/implementation).

1 mark: Identifies a valid influence on outcomes (e.g., state implementation discretion creates variation; conditions attached to funding alter compliance; waivers change program reach).

A federal programme sets national standards but relies on state agencies to administer it. Explain two ways intergovernmental bargaining could change the final policy outcomes across states. (6 marks)

2 marks (1+1): Explains bargaining over funding/conditions (e.g., states accept conditions for funds, or negotiate flexibility), linking to differences in generosity, coverage, or enforcement.

2 marks (1+1): Explains bargaining over administrative discretion/implementation (e.g., staffing, rulemaking, enforcement priorities), linking to variation in access or compliance.

2 marks (1+1): Applies each explanation to cross-state differences (explicitly connects bargaining choice to divergent outcomes between states).