AP Syllabus focus:

‘Speech may be restricted when it creates a clear and present danger; later decisions refined when such limits are constitutional.’

Free speech is strongly protected, but not absolute.

Exterior view of the U.S. Supreme Court building, the institution responsible for developing (and later tightening) First Amendment standards like clear-and-present-danger and imminent-lawless-action. As a note-side visual, it helps students situate case doctrine within the constitutional role of judicial review. Source

This topic traces how the Supreme Court developed the clear and present danger standard and later narrowed government power by requiring tighter links between speech and imminent harm.

The Clear and Present Danger Standard

What the test tries to do

The Court has long wrestled with when speech crosses from protected expression into punishable conduct. The clear and present danger framework addresses the syllabus point that speech may be restricted when it creates a clear and present danger, while recognising that later cases refined how that danger must be shown.

Clear and present danger — a First Amendment standard asking whether speech creates a sufficiently serious, immediate risk of harm that government may constitutionally punish or restrict it.

A key feature is context: the same words may be protected in ordinary politics but punishable in a crisis (such as wartime) if the risk of harm becomes more immediate and concrete.

Early use in wartime speech cases

The standard is most famously associated with Schenck v. United States (1919), where the Court upheld convictions under the Espionage Act for anti-draft leaflets during World War I.

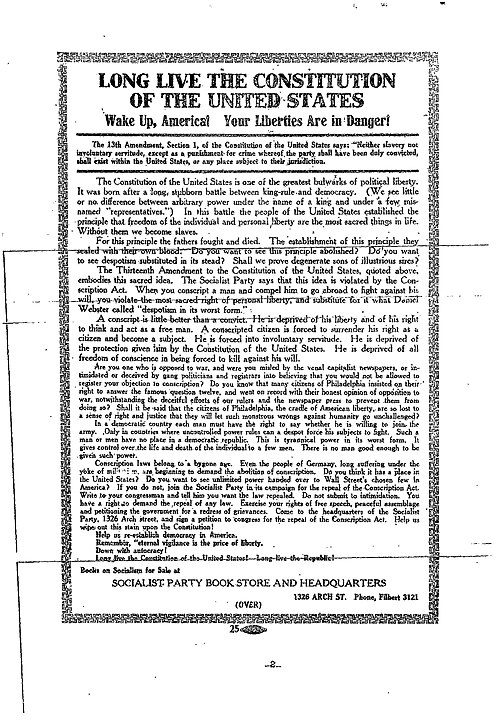

Obverse (front) of the anti-draft leaflet that triggered the prosecution in Schenck v. United States (1919). Seeing the document itself helps explain why the Court emphasized wartime context when evaluating whether speech created a sufficiently serious and immediate risk to government interests. Source

Justice Holmes likened certain speech to falsely shouting fire in a crowded theatre, emphasising that government may act when speech poses a serious risk.

Core idea in early applications:

Government interests (national security, military operations) could justify punishment

The “danger” assessment was often deferential to legislatures during war

Refinements: From “Danger” to “Imminent Incitement”

Holmes and Brandeis: sharpening the standard

Soon after Schenck, Holmes (in dissent) argued for stronger protection unless speech posed an immediate threat. Dissents in cases like Abrams v. United States (1919) and Whitney v. California (1927) stressed that fear of unpopular ideas is not enough; suppression should be limited to situations where harm is truly impending.

These arguments laid groundwork for later doctrine by insisting that:

Mere advocacy of ideas is generally protected

Government must show more than speculative or remote harm

Cold War pressures and doctrinal inconsistency

During the Red Scare and Cold War, the Court sometimes upheld restrictions on alleged subversive advocacy (for example, under anti-communist laws), applying versions of “danger” that did not always require immediate harm. This period illustrates why the syllabus notes that later decisions refined the original approach: the Court moved away from broader, fear-based suppression toward stricter requirements.

The Modern Rule: Brandenburg’s “Imminent Lawless Action”

The current constitutional baseline

In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Court replaced looser danger-based approaches with a more speech-protective test.

The government generally cannot punish advocacy unless it is tightly connected to imminent unlawful conduct.

Imminent lawless action — the modern First Amendment test permitting punishment of advocacy only when the speech is intended to provoke immediate illegality and is likely to produce that illegality.

A crucial shift is that the Constitution does not allow punishment simply because speech is extreme, offensive, or politically threatening. The focus is on incitement with immediacy and likelihood.

Elements students should be able to identify

To lawfully restrict speech under the Brandenburg approach, courts look for:

Intent: the speaker aims to cause lawbreaking (not merely express a belief)

Imminence: the unlawful action is expected right away, not at some indefinite future time

Likelihood: the speech is realistically capable of producing that immediate unlawful action

Incitement — speech directed at provoking others to engage in unlawful conduct, which may be punishable only under a demanding standard requiring intent, imminence, and likelihood.

How to Apply the Doctrine in Case Reasoning

What the government must prove (and what is not enough)

Under modern doctrine, government typically must do more than point to dangerous ideas.

Usually insufficient by itself:

abstract advocacy of violence as a concept

membership in a radical group without proof of inciting conduct

speech that is provocative but not connected to imminent action

More likely to justify restriction:

coordinated urging of immediate unlawful acts to a ready audience

circumstances showing the audience is likely to act at once

Why the “later refinements” matter

The move from clear and present danger to imminent lawless action reflects the Court’s tightening of constitutional limits on censorship. The refinement protects robust political debate by requiring a close, immediate connection between words and unlawful acts before punishment is allowed.

FAQ

Not usually. Modern incitement doctrine largely follows Brandenburg, though the phrase may appear historically or rhetorically in opinions.

Courts look for immediacy in time and situation: a near-term call to unlawful action in circumstances where action could occur straightaway.

From context and content, such as explicit directives, repetition, planning, targeting a primed audience, or coordination with anticipated events.

No. The issue is whether the advocacy was intended and likely to produce imminent illegality, not whether harm ultimately happened.

Yes, but it is fact-specific. Key issues include audience readiness, platform dynamics, and whether the post is a direct, immediate prompt likely to trigger unlawful action.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define “clear and present danger” and state what it allows government to do.

1 mark: accurate definition (serious/immediate risk of harm from speech)

1 mark: states it can justify restricting/punishing speech in that circumstance

(6 marks) Explain how later Supreme Court decisions refined the clear and present danger approach when judging when speech may be restricted.

2 marks: explains refinement toward stronger protection (not enough that ideas are unpopular or merely risky)

2 marks: identifies Brandenburg-style requirements (intent + imminence + likelihood, or equivalent)

2 marks: applies refinement conceptually to government burden (must show close, immediate link between speech and unlawful action)