AP Syllabus focus:

‘First Amendment speech doctrine reflects ongoing efforts to balance individual freedom with laws aimed at protecting social order and safety.’

Free speech cases often turn on trade-offs: protecting robust public debate while allowing government to maintain safety, protect rights, and keep institutions functioning. The Supreme Court manages these conflicts by using structured legal tests.

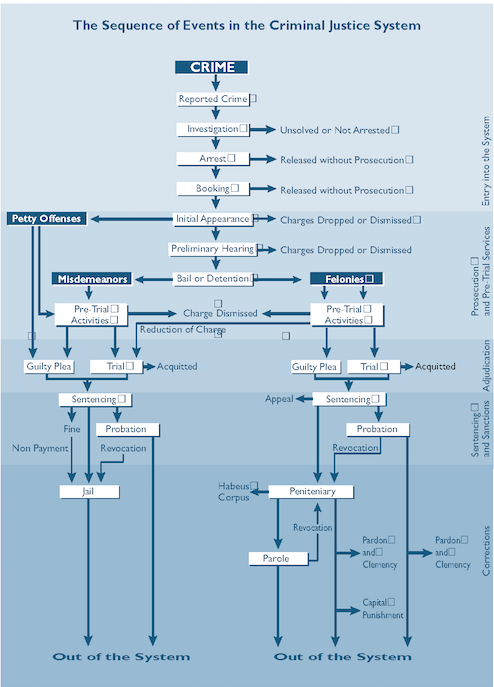

This diagram maps the major procedural stages and branching decision points in the U.S. criminal justice system (e.g., investigation, charging, trial/plea, sentencing, appeal). It models how legal institutions translate broad principles into step-by-step processes with predictable “if/then” pathways. That same logic—structured stages and burden-shifting checkpoints—also underlies First Amendment doctrinal tests. Source

The Core Tension: Liberty vs. Order

The First Amendment strongly protects expressive freedom, but it has never been treated as absolute. In disputes, the Court weighs:

The value of the expression to democratic self-government (political speech is usually most protected)

The government’s objective (safety, protecting others’ rights, preserving orderly processes)

The fit between the law and the goal (how directly and narrowly the restriction addresses the problem)

The risk of chilling effect (whether people will self-censor out of fear of punishment)

This balancing is visible in how the Court decides which rules trigger the toughest review and which rules get more deference.

How the Court Structures “Balancing” with Levels of Review

Rather than openly “weighing” interests in an ad hoc way, the Court often channels balancing into doctrinal frameworks that set a predictable burden of justification for the government.

Content-Based vs. Content-Neutral Rules

A major dividing line is whether the government regulates speech because of what it says.

Content-based restriction: A law that targets speech because of its message, ideas, or viewpoint.

Content-based restrictions are treated as especially dangerous because they can become tools for censorship or political advantage.

This photograph shows protestors carrying signs outside an embassy—an archetypal public, political demonstration where the government may be tempted to regulate speech because of its message. It usefully concretizes the idea that content-based restrictions can distort public debate by singling out particular topics or viewpoints. In First Amendment doctrine, that censorship risk is a key reason content-based rules typically trigger the most demanding judicial review. Source

Content-neutral restriction: A law that regulates the conditions of expression (such as logistics) without targeting the message.

Even when a rule is labelled content-neutral, the Court may look at real-world purpose and effects to ensure the government is not disguising censorship as regulation.

Strict Scrutiny vs. Intermediate Scrutiny (the Government’s Burden)

When review is demanding, the government must supply stronger evidence and tighter reasoning.

Strict scrutiny: The most demanding constitutional test; the government must show a compelling interest and that the law is narrowly tailored (least speech-restrictive approach reasonably available).

Strict scrutiny reflects the Court’s view that protecting liberty requires scepticism of government motives when ideas are being targeted.

Intermediate scrutiny: A mid-level test; the government must show an important interest and that the law is substantially related to achieving it without unnecessarily burdening speech.

Intermediate scrutiny is one way the Court accommodates social order concerns while still requiring meaningful justification.

Tools the Court Uses to Protect Order Without Gutting Speech

The Court frequently narrows government power by requiring precision and by insisting that regulation leave breathing space for lawful expression.

Narrow Tailoring and Overbreadth Concerns

To prevent broad crackdowns justified by isolated harms, the Court is wary of laws that:

Sweep in substantial protected speech along with unprotected conduct

Use vague terms that invite arbitrary enforcement

Allow officials excessive discretion to decide who may speak

These concerns connect directly to social order: vague or sweeping laws may seem efficient, but they risk selective enforcement that undermines legitimacy and democratic accountability.

Protection of the Political Process

The Court often treats speech tied to elections, protest, and public debate as central to self-government, meaning:

The government’s “order” rationale must be especially persuasive

Restrictions that skew public discourse can be treated as constitutionally suspect

Courts scrutinise whether the state is trying to suppress dissent rather than address a genuine harm

The Evolving Nature of the Balance

Because social conditions and communication technologies change, the Court’s balance can shift over time. Its approach reflects:

Changing assessments of what counts as a serious threat to public safety

Changing views about the harms of censorship and the importance of open debate

Disagreements among justices about whether courts should defer to legislatures or aggressively protect expressive liberty

This is why First Amendment speech doctrine is best understood as an ongoing attempt to keep both commitments in view: individual freedom and the practical necessities of social order and safety.

FAQ

Courts may look beyond the text to purpose and context.

They consider:

legislative history or official statements

enforcement patterns (who is targeted)

whether the rule is triggered by disagreement with the message rather than by neutral concerns (e.g., congestion)

If the government’s justification depends on the content of the speech, the rule is more likely to be treated as content-based.

It usually means the government must show it addressed the specific harm without sweeping more speech than necessary.

Indicators a law is not narrowly tailored include:

broad bans when narrower rules would address the harm

heavy penalties that deter lawful expression

discretionary licensing schemes without clear criteria

Evidence and fit matter, not just asserted fears.

Because speech is uniquely vulnerable to self-censorship: people may stay silent rather than risk investigation, punishment, or public backlash.

Courts treat chill as a constitutional harm because it:

reduces participation in democratic debate

disproportionately silences marginal or unpopular speakers

can occur even if few prosecutions happen

This concern pushes courts towards clarity and restraint in regulation.

No. Courts tend to be more sceptical when order-based justifications resemble dislike of disruption or dissent.

Goals are more persuasive when tied to:

concrete safety risks

protecting others’ legal rights

maintaining the functioning of key public systems

Goals are weaker when they rely on vague claims like preserving “respect” or avoiding embarrassment to officials.

Separate opinions can reframe the problem and supply alternative tests that later majorities adopt.

They can:

criticise existing standards as too permissive or too restrictive

propose clearer rules for lower courts

influence public and academic debate that feeds into future litigation

Over time, these arguments can shift doctrine as Court membership and social conditions change.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Identify and briefly explain one way the Supreme Court distinguishes between speech regulations that are more likely to be upheld and those that are more likely to be struck down.

1 mark: Identifies a valid distinction (e.g., content-based vs content-neutral; strict scrutiny vs intermediate scrutiny).

1 mark: Briefly explains the distinction (e.g., content-based targets the message; content-neutral regulates conditions).

1 mark: Links to likely outcome (e.g., content-based usually faces stricter review and is harder to justify).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Explain how the Supreme Court balances First Amendment liberty with laws aimed at social order and safety, using at least two doctrinal tools or principles.

1 mark: Explains the core tension (free expression vs safety/order).

2 marks: Describes two doctrinal tools/principles (1 mark each), such as:

content-based vs content-neutral classification

strict scrutiny requirements (compelling interest, narrow tailoring)

intermediate scrutiny (important interest, substantial relation)

concerns about vagueness/overbreadth or chilling effect

1–2 marks: Applies each tool to balancing (e.g., why stricter review protects against censorship; why tailoring protects order while preserving speech).

1 mark: Overall coherence: shows how structured tests operationalise balancing rather than pure ad hoc weighing.