AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Supreme Court supports a strong presumption against prior restraint—government censorship before publication.’

Freedom of the press is central to democratic accountability. In U.S. constitutional law, the hardest free-press cases involve prior restraint, where government tries to stop publication in advance rather than punish unlawful speech afterward.

Core Idea: Freedom of the Press

The First Amendment protects the press’s ability to gather information, publish criticism, and inform the public without undue government control. While the press has no general immunity from neutral laws (e.g., taxes, some subpoenas), courts treat government censorship as uniquely dangerous because it blocks public debate before it occurs.

Prior Restraint: The Key Doctrine

Prior restraint is treated as the most suspect form of speech regulation because it prevents ideas from reaching the public and encourages self-censorship.

Prior restraint: a government action (often a licensing scheme or court injunction) that prevents speech or publication before it happens.

The Presumption Against Prior Restraint

Consistent with the syllabus focus, the Supreme Court has articulated a strong presumption against prior restraint—meaning the government bears an exceptionally heavy burden to justify it.

The photograph shows the west façade of the U.S. Supreme Court building, the institution that announces and applies First Amendment doctrine. Pairing this image with the “presumption against prior restraint” reinforces that the rule is a constitutional standard developed through Supreme Court decisions, not merely a policy preference. Source

In practice, this makes prior restraints rarely constitutional, even when the government claims serious harms.

Why the Court Is Especially Skeptical

Historical concerns: English and colonial “licensing” systems were tools to suppress dissent; the First Amendment was written against that backdrop.

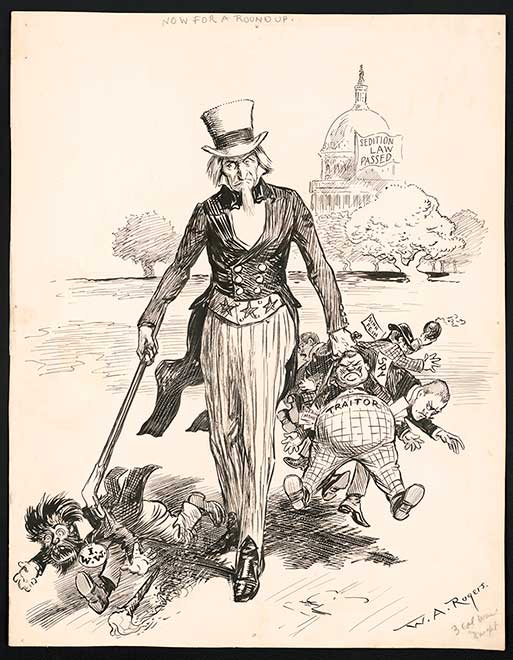

This Library of Congress exhibit item reproduces a 1918 newspaper political cartoon responding to expanded federal authority during World War I–era surveillance and censorship. It provides historical context for why U.S. free-expression doctrine treats censorship mechanisms with suspicion: once government is empowered to suppress dissent, the boundary between “security” and silencing criticism can blur. Source

Structural role of the press: Press freedom supports checks on power, especially by exposing official misconduct.

Chilling effect: If publishers fear pre-publication bans, they may avoid lawful but controversial reporting.

Procedural danger: Prior restraint often places censorship decisions in the hands of government officials or hurried courts.

Major Forms of Prior Restraint

Licensing and Permits

A law requiring government permission to publish (or granting broad discretion to deny permission) is a classic prior restraint. Courts are wary of systems that allow officials to decide what may be printed.

Court Injunctions (“Gag Orders” on Publication)

Courts sometimes issue orders barring publication of specific material. Because injunctions are targeted and enforceable through contempt, they can be even more effective than broad criminal laws—so the Court scrutinises them closely.

Landmark Case Foundations (What Students Should Know)

Near v. Minnesota (1931)

Near is the foundational case establishing that prior restraints on publication are generally unconstitutional. Minnesota tried to shut down a newspaper as a “public nuisance” for publishing scandalous material. The Court rejected this approach because it amounted to pre-publication censorship rather than punishment after a proven legal violation.

Key takeaways aligned to the doctrine:

Post-publication punishment (e.g., for defamation, if proven under the proper standard) is different from stopping publication in advance.

Prior restraint is not automatically impossible, but it is presumptively invalid.

The Narrow Space for Exceptions

The Court has suggested only extraordinary situations might justify prior restraint, such as:

Preventing publication of specific, immediate harms tied to national security, military operations, or similarly urgent threats

Stopping certain forms of unprotected expression where advance restraint is tightly justified by law and procedure

The doctrinal point is not that exceptions are common, but that the starting rule is freedom from censorship.

How This Fits into First Amendment Analysis

When evaluating a press-freedom dispute involving prior restraint, focus on:

Timing: Is government acting before publication (prior restraint) or after publication (punishment)?

Form: Is it a licence/permit requirement or a court injunction?

Burden: The government must overcome a heavy presumption of unconstitutionality.

Practical impact: Does the rule give officials broad discretion, or does it function as a censorial tool?

FAQ

Licensing blocks publication system-wide through prior permission.

An injunction blocks specific content via a court order enforceable by contempt.

Yes, the principle targets censorship mechanisms regardless of medium.

Courts still examine the specific regulatory structure and discretion granted.

Courts are cautious because it directly censors the press.

They often prefer alternatives (jury sequestration, venue change) over publication bans.

No. The press can be subject to neutral laws.

The special concern arises when the law operates like censorship before publication.

Clear legal standards and minimal official discretion.

Prompt judicial review and narrow, specific scope reduce (but rarely eliminate) constitutional concerns.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define prior restraint and state the Supreme Court’s general position on it under the First Amendment.

1 mark: Correct definition (government prevents publication/speech before it occurs, e.g., injunction/licensing).

1 mark: States the Court applies a strong presumption against it / it is rarely constitutional.

(6 marks) Explain why the Supreme Court is highly sceptical of prior restraints, referring to Near v. Minnesota (1931).

1 mark: Identifies Near as a key case limiting prior restraint.

1 mark: Explains Minnesota’s action functioned as pre-publication censorship (injunction/shutting a paper).

1 mark: States the presumption against prior restraint / heavy burden on government.

1 mark: Gives a reason (chilling effect/self-censorship).

1 mark: Gives a reason (historical opposition to licensing/censorship).

1 mark: Distinguishes prior restraint from post-publication punishment (e.g., defamation liability after trial).