AP Syllabus focus:

‘Major political events can influence the development of individual political attitudes, illustrating the process of political socialization.’

Political attitudes are not fixed. Major events can rapidly reshape how people interpret government, rights, and national priorities, often leaving long-lasting “imprints” that help explain shifts in public opinion and political behaviour.

How major events influence political attitudes

Major events affect attitudes because they change the information citizens receive, the emotions they feel, and the incentives elites and media have to frame issues in particular ways. Events can be sudden (a terrorist attack) or slow-moving but salient (a prolonged economic downturn).

Key idea: events as “teachable moments”

Major events function as high-attention moments when people who normally pay limited attention to politics update their beliefs.

Political socialization: The process by which individuals develop political beliefs, values, opinions, and behaviours over time, shaped by life experiences and social contexts.

Events illustrate political socialization in real time: citizens connect personal experiences (job loss, military service, pandemic disruptions) to political interpretations (trust in institutions, support for policies, views on government capacity).

Mechanisms: why attitudes change after major events

1) Heightened salience and issue reprioritisation

Events elevate some issues above others, changing what people think government should focus on.

After a security crisis, national security and public order often become more salient.

After an economic shock, jobs, inflation, and economic inequality may dominate attitudes about government performance.

After a public health emergency, collective risk can increase attention to capacity and coordination.

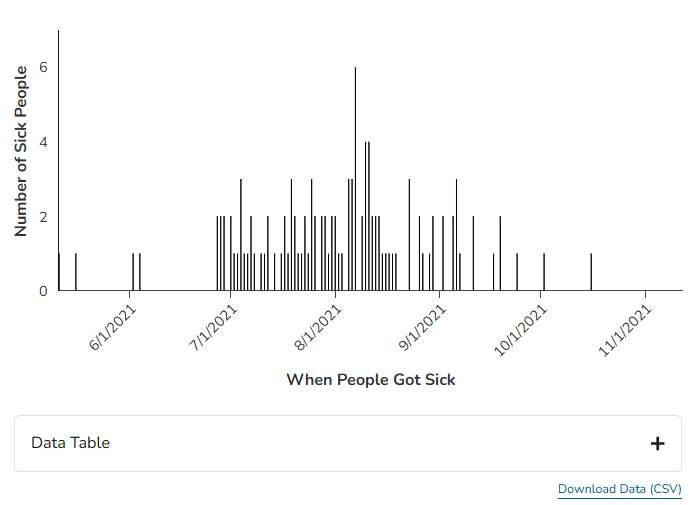

This CDC example shows an epidemic curve (epi curve), which plots the number of cases over time during an outbreak. The shape of the curve helps explain why public attention and policy urgency can surge quickly when cases rise and then fade or shift as trends change. It is a practical visualization of how crises create high-information, high-emotion conditions that can reshape attitudes about government capacity and coordination. Source

2) Information, misinformation, and uncertainty

When facts are incomplete, citizens rely more on:

trusted messengers (local leaders, national officials, experts)

partisan cues (how party leaders interpret the event)

media narratives (which facts are amplified and which are ignored)

High uncertainty can polarise attitudes because different groups accept different “credible” accounts of what happened and who is responsible.

3) Emotional effects and threat perception

Events can generate fear, anger, empathy, or pride—emotions that shape political judgement.

Fear can increase support for protective policies and acceptance of government expansion.

Anger can increase blame, protest activity, and demands for accountability.

Empathy can increase support for relief efforts and social support policies.

4) Elite framing and party sorting

Elected officials, candidates, and interest groups frame events to support preferred policies. Citizens often adopt these frames, especially when they align with existing identities.

Competing frames can pull the same event in different ideological directions (e.g., “government failure” versus “need for more resources”).

Over time, repeated framing can contribute to party sorting, where people align their issue positions more consistently with one party.

5) Performance evaluations and institutional trust

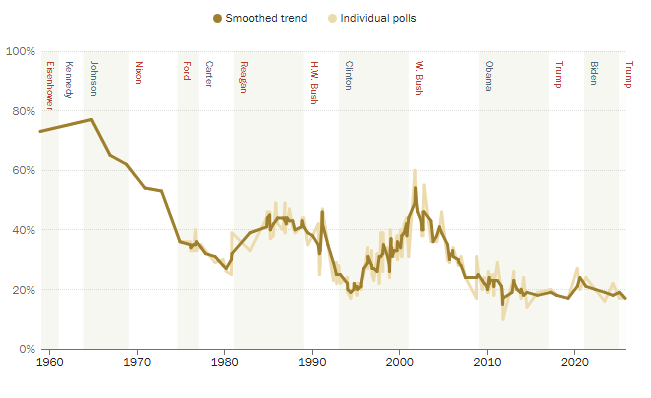

This chart tracks the share of Americans who say they trust the federal government to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time” across multiple decades. The long time horizon makes it easy to see both short-term shocks (temporary surges or drops after salient events) and longer-run erosion or recovery in institutional trust. It provides an empirical anchor for connecting major political events to shifting evaluations of government performance. Source

Major events act as stress tests for institutions. Attitudes shift based on perceived competence and fairness.

Effective responses can increase trust in government and belief in institutional legitimacy.

Perceived incompetence, corruption, or unequal treatment can decrease trust and increase cynicism.

Time horizon: short-term shocks vs long-term legacies

Short-term opinion movement

Immediately after major events, public opinion may shift sharply because attention is high and people seek clear answers. These changes may fade as daily life resumes and new issues emerge.

Long-term “imprinting”

Some events create durable attitudes, especially when they:

occur during politically formative years (late teens to early adulthood)

directly affect a person’s family, safety, or economic security

are reinforced over time by continued conflict, policy debate, or recurring crises

These long-term effects show how major political events can influence the development of individual political attitudes, illustrating the process of political socialization.

What students should be able to do (skills focus)

Explain at least two mechanisms linking a major event to attitude change (salience, emotion, elite cues, trust).

Distinguish between temporary shifts in opinion and longer-lasting changes tied to identity and life experience.

Describe how different groups can react differently to the same event based on prior beliefs, social context, and information sources.

FAQ

No. Direction depends on perceived responsibility, personal impact, and which frames dominate.

Different communities can interpret the same event through distinct historical experiences and local conditions.

Engagement is more likely when people feel efficacy and see clear avenues for action.

Withdrawal is more likely when people feel overwhelmed, distrustful, or believe participation will not change outcomes.

Crises can raise demand for protection while also revealing failures.

People may support expanded powers in one area (security/health) yet distrust agencies seen as incompetent or biased.

Interpersonal discussion filters information and reinforces norms.

Group belonging can intensify conformity to shared interpretations, especially when uncertainty is high.

They may institutionalise responses through new laws, agencies, or funding streams.

They may also repeatedly message a narrative of success or blame to keep the event salient for future elections.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one way a major political event can influence an individual’s political attitudes.

1 mark: Identifies a valid mechanism (e.g., increased issue salience, emotional response, elite cues, trust in institutions).

1 mark: Explains how that mechanism changes attitudes (e.g., fear increases support for security measures; poor performance reduces trust).

(6 marks) Analyse how a major national crisis can illustrate political socialisation by shaping political attitudes. In your answer, refer to (i) elite or media framing and (ii) trust in government.

1–2 marks: Defines or accurately describes political socialisation as attitudes formed through experiences and social context.

1–2 marks: Explains elite/media framing (how leaders/media interpret the crisis, provide cues, and influence public evaluations).

1–2 marks: Explains trust in government effects (competence/fairness evaluations increasing or decreasing legitimacy and support for policy).

Up to 2 marks for analysis: Connects mechanisms to attitude formation over time (short-term vs longer-term change) and/or recognises differing group reactions.