AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political socialization shapes political attitudes, and those attitudes in turn influence a person’s political ideology.’

Political ideology does not appear fully formed; it develops as people absorb cues from their environment. Over time, repeated experiences shape attitudes, and patterns across those attitudes solidify into an ideological worldview.

The core pathway: socialization → attitudes → ideology

Political socialization is the broad, long-term learning process that builds the raw materials of political thinking.

Political socialization: the process by which individuals acquire political beliefs, values, opinions, and behavioural tendencies.

A key product of socialization is a set of political attitudes, which later become organised into political ideology.

Political attitude: a learned predisposition to evaluate a political object (an issue, group, institution, or leader) positively or negatively.

Attitudes are often issue-specific at first; ideology is the pattern that links them.

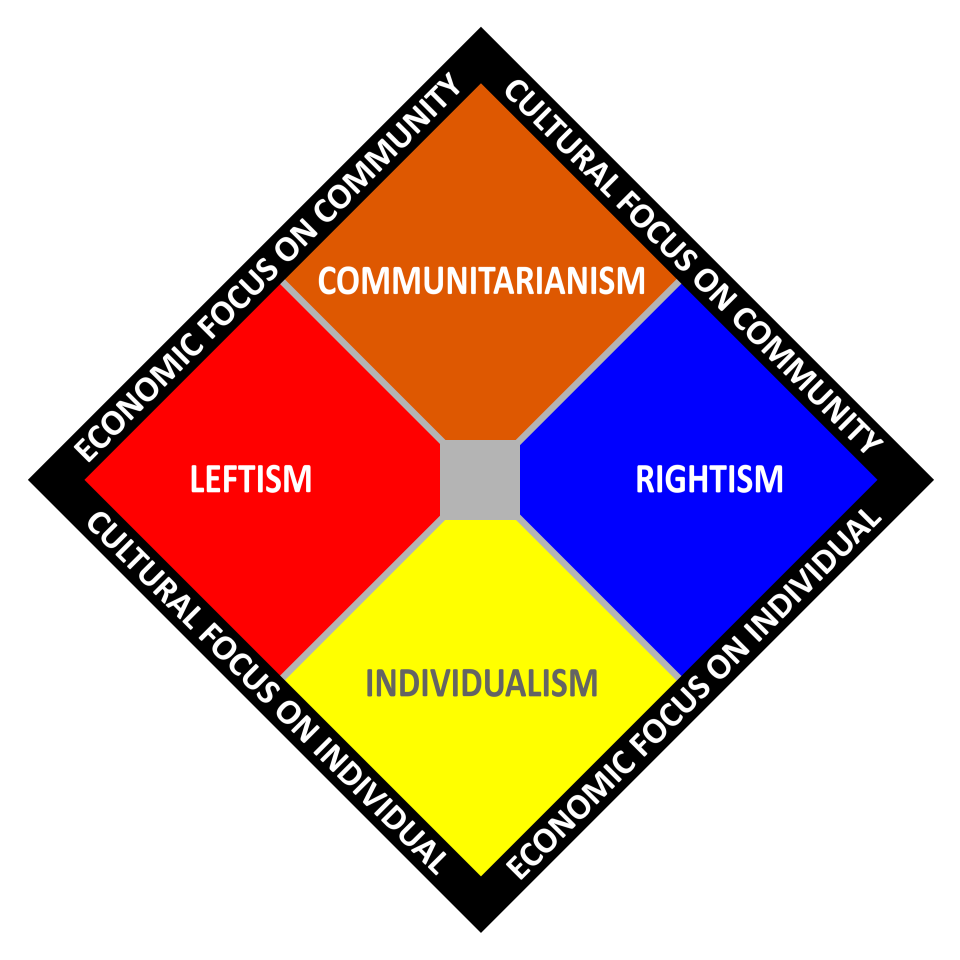

A two-dimensional political spectrum chart that maps political views along both an economic dimension and a cultural (community–individual) dimension. The diagram illustrates why people can share a label like “conservative” yet differ across issues: different combinations of underlying values and attitudes can land in different regions of the space. Source

Political ideology: a more general and consistent set of beliefs about the proper role of government and the meaning of core political values, used to interpret issues and choices.

How attitudes form through political socialization

Political socialization shapes attitudes by repeatedly answering two practical questions for citizens: “What matters?” and “Who is responsible?”

Building blocks that become attitudes

Values and priorities: which goals feel most important (e.g., liberty, equality, tradition, security).

Group-related learning: attachments to social identities (race, religion, region, class) and perceptions of which groups are advantaged or disadvantaged.

Authority and trust: expectations about whether government is effective, fair, and legitimate.

Rules and norms: views about what political behaviour is acceptable (protest, compromise, civil disobedience).

Why attitudes “stick”

Reinforcement: repeated exposure to similar cues strengthens the same evaluation over time.

Selective exposure: people gravitate towards information environments and networks that fit prior views, which stabilises attitudes.

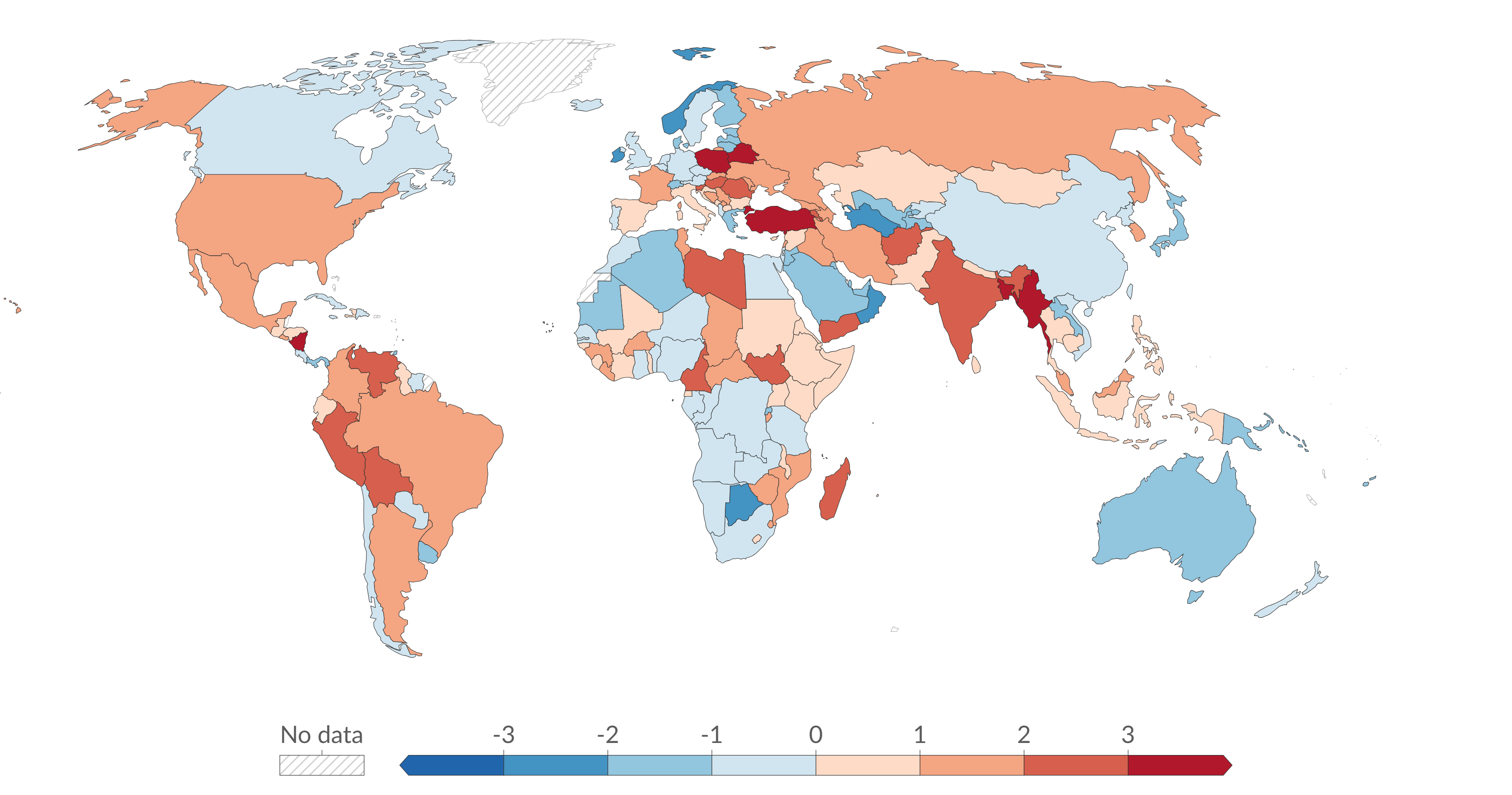

A global choropleth map showing V-Dem’s estimates of how strongly societies are polarized into antagonistic political camps. Higher scores indicate that political differences spill into social relationships, helping illustrate how information environments and group identities can harden attitudes over time. Source

Emotional salience: strong feelings (threat, pride, anger, empathy) increase an attitude’s intensity and durability.

From many attitudes to a coherent ideology

Ideology emerges when a person begins to connect attitudes across issues using a shared logic about government’s role.

Mechanisms that connect attitudes into ideology

Generalisation: a strong stance on one issue becomes a template for others (e.g., “government should stay out” applied across multiple policy areas).

Heuristics (shortcuts): labels like liberal, conservative, or libertarian organise complex issue positions into an understandable bundle.

Partisan and elite cues: trusted leaders, parties, and opinion-makers provide interpretations that link issues together; adopting those links increases ideological consistency.

Value weighting: ideology often reflects which values someone elevates when values conflict (for example, prioritising order over liberty, or equality over limited government).

Constraint: the degree of ideological consistency

Ideological constraint: the extent to which a person’s views on different issues are logically connected and change together.

High constraint means shifts on one issue predict shifts on others; low constraint means attitudes remain more independent and sometimes contradictory. Constraint is shaped by political knowledge, interest, and the clarity of cues in a person’s environment.

What this means for political behaviour

Because ideology is built from attitudes produced by socialization, ideology guides real-world political choices by:

shaping issue preferences and perceived stakes,

structuring candidate evaluation (“Who shares my worldview?”),

influencing participation (when politics feels personally relevant),

affecting openness to compromise and reactions to opposing views.

FAQ

Yes. A person may hold intense positions on a few issues yet lack consistent links across issue areas.

This often happens when attitudes are driven by personal experience or group interest without an organising framework that generalises to other topics.

Symbolic ideology is the label someone adopts (e.g., “conservative”). Operational ideology is the pattern of issue positions they actually hold.

The two can diverge when labels are based on identity, tradition, or group membership rather than policy consistency.

Cross-pressures occur when someone belongs to groups with conflicting political cues.

They can reduce ideological constraint by pulling attitudes in different directions, producing mixed or less predictable combinations of issue preferences.

Elites can supply ready-made interpretations that simplify complexity, especially when citizens lack time or information.

If the cue comes from a trusted source, it can reframe what an issue “means,” shifting the attitude that later feeds into ideology.

Events can alter the weight someone assigns to values (for example, prioritising security more than before), changing how they connect issues.

Rather than switching labels, many people adjust their internal “priority order,” producing a modified but recognisable ideology.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain how political attitudes serve as a link between political socialisation and political ideology.

1 mark: Identifies that political socialisation shapes or produces political attitudes.

1 mark: Explains that patterns across attitudes become organised into an ideology (a broader worldview about government’s role).

(6 marks) Analyse two ways in which political socialisation can turn issue-specific attitudes into a broader political ideology. Use appropriate political science terminology.

1 mark: Accurate use of a relevant term (e.g., political socialisation, political attitudes, ideology, ideological constraint, heuristics, elite cues).

Up to 2 marks: First way explained (e.g., generalisation across issues; value weighting; partisan/elite cues linking issues).

Up to 2 marks: Second way explained (must be distinct from the first).

1 mark: Analysis of how these mechanisms increase coherence/consistency across issues (i.e., stronger ideological constraint).