AP Syllabus focus:

‘Public opinion data that affects elections and policy debates comes from scientific polls, including opinion, benchmark, tracking, and exit polls.’

Scientific polling is a key tool for describing public preferences in a large democracy. Understanding what makes polls “scientific” and how major poll types are used helps explain their influence on campaigns and policy debates.

What Makes a Poll “Scientific”?

A poll is considered scientific when it uses a systematic research design to estimate what a broader population thinks, based on responses from a smaller group.

Scientific poll: A survey designed to measure public opinion using a structured method intended to produce results that approximate the views of a defined population.

Scientific polls share several core features:

A clearly defined target population (for example, all adults, registered voters, or likely voters)

A planned method for selecting respondents so the sample can approximate the population

Standardised interviewing and consistent question wording to reduce measurement error

Transparent reporting of basic design information so audiences can interpret results responsibly

Because they are estimates, scientific polls are best understood as snapshots of opinion at a particular moment, not permanent “facts” about what the public will do.

This figure illustrates a poll estimate (the point) with an error bar showing the margin of sampling error (often expressed as a 95% confidence interval). Visually, it reinforces that a poll result is best interpreted as a plausible range around an estimate—not a single exact number. This helps readers distinguish meaningful differences from differences that may be within sampling uncertainty. Source

Public Opinion Data: Why It Matters

Public opinion data from scientific polls becomes politically meaningful because it is widely circulated and used by:

Candidates and campaigns to allocate resources, choose messages, and identify persuadable groups

Journalists and analysts to interpret momentum, competitiveness, and public priorities

Policymakers and advocates to argue that an issue is popular, urgent, or electorally risky

This influence is not automatic; it depends on whether audiences perceive the polling as credible and relevant to the decision at hand.

Major Types of Scientific Polls

Scientific public opinion data commonly comes from four poll types that serve different purposes across the election cycle.

Opinion (Issue) Polls

Opinion polls measure public preferences on specific issues (for example, support for a policy proposal or evaluations of government performance). They are often used to:

Identify which problems the public considers most important

Compare support across demographic or partisan subgroups

Test reactions to policy framing (without proving causation)

For policy debates, issue polling can shape which arguments officials emphasise and which compromises seem politically feasible.

Benchmark Polls

A benchmark poll is typically conducted early in a campaign (or before a candidate formally runs) to establish a baseline.

Benchmark poll: An early campaign survey used to measure initial name recognition, candidate images, and early vote preferences, creating a starting point for later comparison.

Benchmark data helps campaigns decide whether a candidacy is viable and which themes are most promising, using early measures of support, favourability, and key concerns.

Tracking Polls

A tracking poll repeats similar questions over time to detect movement in opinion during a campaign.

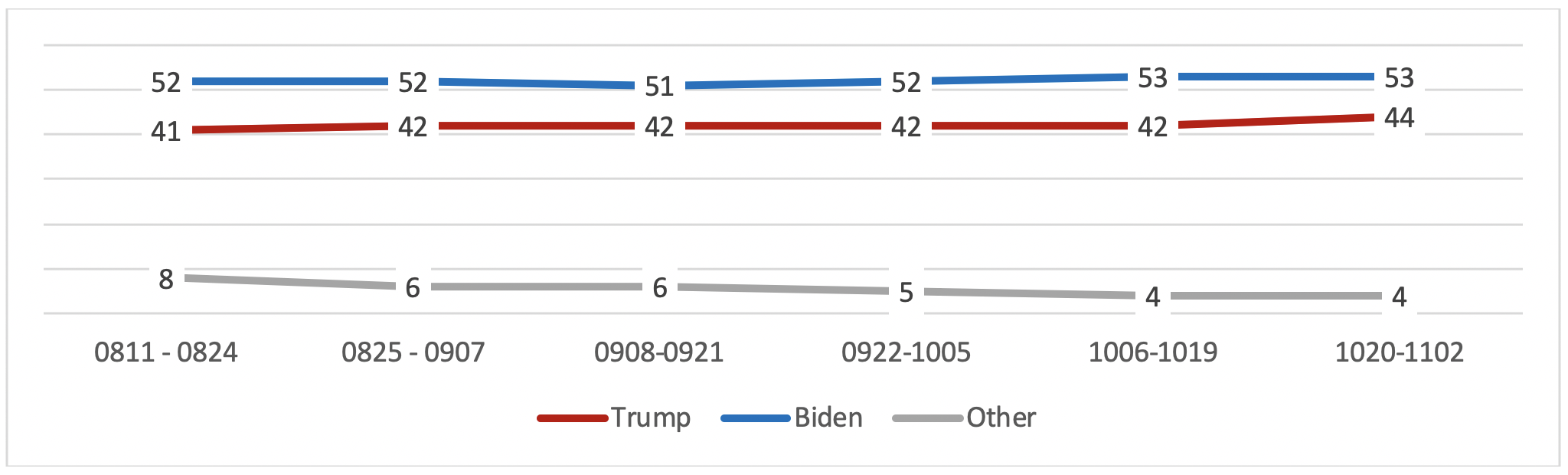

This chart shows repeated estimates of candidate support across successive time windows (waves), which is the central idea of tracking polls. The horizontal axis marks time periods, while the lines summarize how support levels change (or remain stable) as new data come in. Used correctly, this kind of display encourages trend-based interpretation rather than overreacting to a single day’s result. Source

Tracking is useful for:

Monitoring shifts after major events (debates, ads, scandals, economic news)

Seeing whether a message is stabilising support or producing backlash

Separating short-term “bumps” from longer-term trends

Because tracking focuses on change, it is most informative when results are compared across multiple waves rather than treated as a single definitive reading.

Exit Polls

Exit polls are conducted with voters immediately after they cast ballots (or, in some contexts, after they vote early). Their main value is interpretive:

Explaining why voters supported particular candidates or choices

Connecting vote decisions to issues, identity, party, and evaluations of incumbents

Providing evidence used by media and parties to narrate what the election “meant”

Exit poll findings can shape claims about mandates, coalition shifts, and which issues were decisive, even when those claims should be treated cautiously.

FAQ

They match the population to the decision being predicted.

Adults: broad attitudes and values

Registered voters: electoral opinions among eligible participants

Likely voters: models turnout using past behaviour and intention screens

A consistent tendency for a particular polling organisation’s results to lean slightly toward one party/candidate compared with others, often due to recurring design choices (mode, weighting, likely-voter rules).

A rolling average smooths day-to-day noise by combining multiple days of interviews. This can better reveal underlying movement while reducing the impact of any single day’s unusual responses.

Many organisations supplement in-person precinct interviews with telephone/online surveys of early and postal voters, then combine sources using weighting to approximate the total electorate.

Weighting adjusts the sample to better match the population (e.g., age, education, region, party ID). It aims to reduce bias from over- or under-represented groups, but relies on accurate benchmarks.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Distinguish between a benchmark poll and a tracking poll.

1 mark: Defines benchmark poll as establishing an early baseline.

1 mark: Defines tracking poll as repeated measurement over time.

1 mark: Explains that tracking is used to detect change compared with the benchmark/baseline.

(6 marks) Explain how opinion polls and exit polls produce different kinds of public opinion data that can affect elections and policy debates.

1 mark: Identifies opinion polls as measuring issue preferences/attitudes.

1 mark: Explains how issue polling can influence campaign messaging or policy argumentation.

1 mark: Identifies exit polls as surveying voters after voting.

1 mark: Explains exit polls’ role in interpreting election outcomes (e.g., voter motivations/coalitions).

1 mark: Compares the timing/purpose difference (pre-election issue climate vs post-vote interpretation).

1 mark: Notes that both can shape narratives used by media/elites in elections and debates.