AP Syllabus focus:

‘Parties have adapted to candidate-centered campaigns that emphasize the candidate over the party and have weakened parties’ roles in nominating candidates.’

Candidate-centered campaigning has reshaped American elections by shifting power away from party organisations and towards individual candidates. Understanding why this happened clarifies modern nominations, messaging, fundraising, and the limits of party control.

What “candidate-centered” means

Modern campaigns often revolve around the individual’s brand, biography, and personal issue emphasis more than a shared party programme or party leaders’ direction.

Candidate-centered campaign: An election strategy in which the candidate, rather than the political party, is the main focus for fundraising, media coverage, messaging, and voter mobilisation.

Candidate-centered politics does not eliminate parties, but it reduces their ability to set priorities, control nominations, and coordinate unified campaign messages across races.

Why candidate-centered campaigns emerged

Primary elections and the decline of party “gatekeeping”

As nominations became more directly shaped by voters, candidates could bypass party insiders who once played a stronger role in selecting nominees.

This photograph shows a U.S. presidential election ballot, illustrating the voter-facing mechanics that underpin party nominations and general-election choices. In a candidate-centered era, campaigns often focus on ensuring the candidate’s name recognition and personal appeal translate into selections on ballots like this one. Source

Primaries incentivise candidates to build a personal following and distinct message to win intra-party contests.

Outsider candidates can appeal directly to voters without waiting for party leaders’ approval.

Factional competition inside parties encourages differentiation from other same-party contenders.

Media environment and personal branding

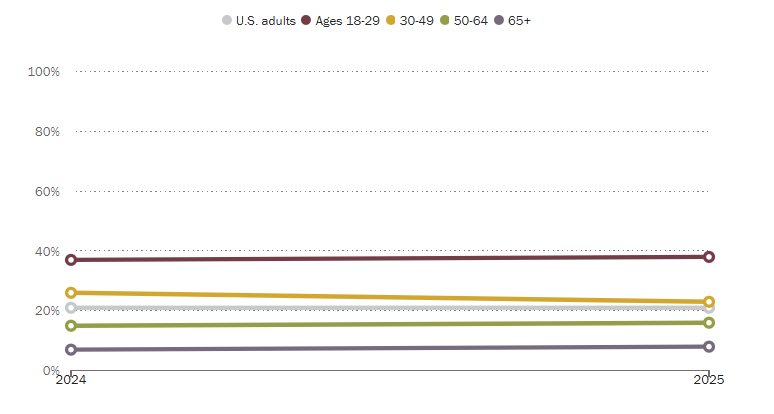

This Pew Research Center chart shows the share of U.S. adults (and age groups) who say they regularly get news from “news influencers” on social media. The age breakdown helps explain why campaigns increasingly invest in candidate-specific image management and personality-driven communication to reach voters in today’s media environment. Source

Candidate-centered campaigning is reinforced by a system that rewards individual visibility.

Candidates seek earned media (news attention) by crafting personal narratives and generating coverage-friendly moments.

Television and online content often highlight candidate traits (competence, empathy, leadership) because they are easier to communicate than complex party agendas.

Debates and interviews frame elections as comparisons between individuals, pushing campaigns to prioritise image management.

Fundraising and professionalisation

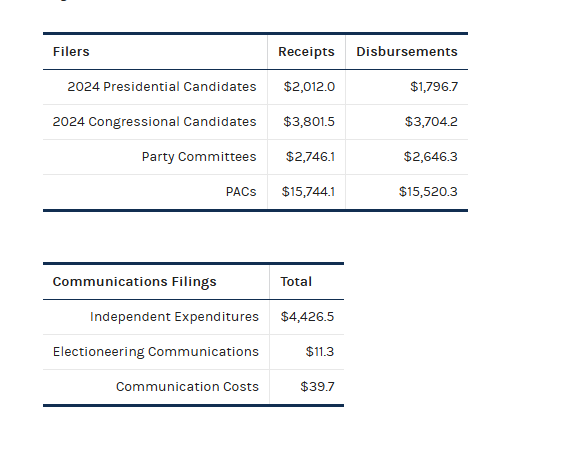

This Federal Election Commission table summarizes total receipts and disbursements across major political actors (presidential candidates, congressional candidates, party committees, and PACs) for the 2023–2024 election cycle. Seeing candidates listed alongside parties and PACs helps clarify how modern campaigns can build substantial, candidate-run fundraising operations rather than relying primarily on party organizations. Source

Candidates increasingly assemble their own campaign infrastructures.

Reliance on professional consultants (pollsters, media strategists, field directors) supports customised messaging for a candidate’s coalition.

Candidates build personal donor networks and email lists that can outlast any single party cycle.

Campaigns invest in tailored communications that may diverge from national party messaging to fit a district or state.

How party control weakens (especially in nominations)

Candidate-centered campaigns weaken party control most clearly at the nomination stage, where parties have less ability to determine who represents them.

Reduced screening: Parties find it harder to block inexperienced or divisive contenders when voters choose nominees directly.

Less message discipline: Nominees may take positions that energise a primary electorate even if party leaders worry about general-election appeal.

Independent organisations: Candidates often construct parallel structures (fundraising, data, volunteers) that are not fully directed by party committees.

Personal loyalty over party loyalty: Staff, donors, and activists may attach to the candidate as an individual rather than to the party organisation.

Campaign strategy consequences

Once nominated, candidates still face incentives to run as “their own person.”

In competitive areas, candidates may distance themselves from party labels to appeal to moderates or cross-pressured voters.

In safe partisan areas, candidates may prioritise base mobilisation, again driven by personal style and issue emphasis rather than party leadership preferences.

What this change means for parties and governance

Candidate-centered campaigns alter how parties function as organisations and how effectively they coordinate elected officials.

Parties may struggle to produce consistent policy accountability, because candidates campaign on personalised promises rather than a unified platform.

Party leaders have fewer tools to prevent intra-party conflict, which can spill into governing and reduce cohesion.

Elections can become more volatile when voters respond to candidate qualities (scandals, charisma, perceived competence) instead of stable party attachments.

These dynamics reflect the syllabus focus: parties have adapted to a world where candidates can build support independently, and parties’ roles in nominating candidates have weakened.

FAQ

They may use endorsements, strategic funding, and access to party networks.

They can also coordinate informal pressure on donors and activists to consolidate behind preferred contenders.

A party brand is a broad, shared reputation linked to the party label.

A candidate brand is an individualised image built from biography, tone, competence cues, and tailored issue emphasis.

Voters may prioritise visibility, charisma, or outsider identity over governing experience.

With weaker gatekeeping, parties have fewer opportunities to vet contenders before they reach primary voters.

They can help if a strong candidate expands the party’s coalition or wins in difficult territory.

However, the party may gain seats without gaining long-term organisational control over that candidate.

Voters may judge performance against personalised promises rather than party programmes.

This can blur responsibility, especially when candidates campaign independently but govern within party coalitions.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define a candidate-centred campaign and state one way it can weaken party control in US elections.

1 mark: Defines candidate-centred campaigning as focusing campaign activity on the individual candidate rather than the party.

1 mark: Explains one weakening effect (e.g. candidates bypass party leaders in nominations; reduced party message discipline; independent fundraising/organisation).

(6 marks) Explain two reasons why US campaigns have become more candidate-centred and analyse two effects this has on political parties’ control over nominations and campaign messaging.

1 mark: Reason 1 identified (e.g. primaries reduce party gatekeeping).

1 mark: Reason 1 explained.

1 mark: Reason 2 identified (e.g. media rewards personal branding; professional consultants and candidate-run fundraising).

1 mark: Reason 2 explained.

1 mark: Effect 1 analysed (e.g. parties cannot screen/select nominees effectively; outsiders can win).

1 mark: Effect 2 analysed (e.g. weaker message discipline; candidates distance from party label or personalise issue priorities).