AP Syllabus focus:

‘Parties may adjust policies and messaging to appeal to different demographic coalitions in order to win elections.’

Political parties in the United States are coalitions that must continually assemble winning voter majorities. They do this by adapting policy agendas and campaign messages to attract, retain, and mobilise key demographic groups across elections.

Core idea: building demographic coalitions

Parties seek durable electoral support by linking groups’ identities and interests to party priorities and candidate brands. A coalition is rarely permanent; it can expand, fray, or shift as issues, candidates, and social conditions change.

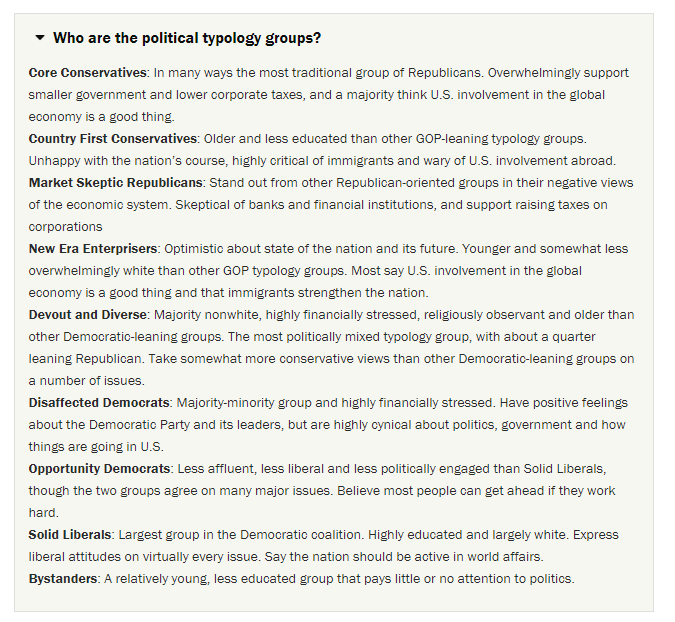

This chart summarizes Pew Research Center’s 2021 Political Typology, which segments Americans into distinct, labeled groups based on political values and attitudes. It helps illustrate why party coalitions are assembled from multiple subgroups with different priorities, creating internal tensions and opportunities for realignment. Source

Demographic coalition: A party’s mix of supporting social groups (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, religion, education, region) whose combined votes can produce electoral majorities.

Coalition-building is strategic: parties weigh which groups are persuadable, which are reliably supportive, and which can be turned out at higher rates.

Why demographics matter to parties

Demographic groups often differ in:

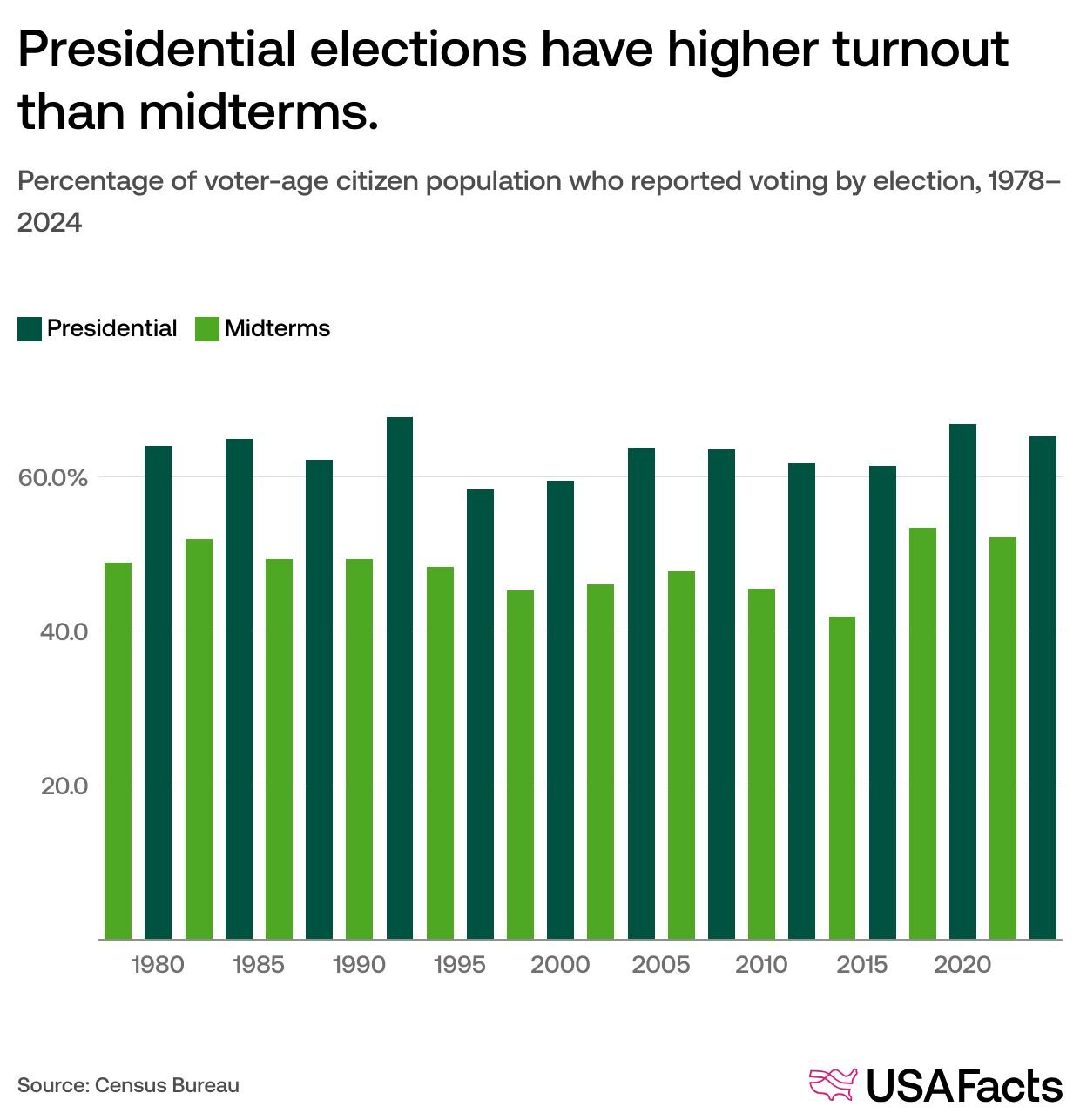

This line graph shows that voter turnout rises sharply with age, with citizens 65+ consistently voting at higher rates than younger adults across presidential elections. It clarifies why parties often invest heavily in mobilizing high-turnout groups while designing different outreach strategies for lower-turnout cohorts. Source

Policy preferences (taxes, healthcare, immigration, education, policing)

Political identities (religion, community ties, union membership, ideology)

Turnout patterns (who votes regularly vs. intermittently)

Geographic concentration (swing states/districts vs. safe areas)

Policy adaptation: changing what the party prioritises

Parties may adjust policy positions to align with a target group’s priorities or to reduce conflict inside the coalition.

Common policy-based strategies

Agenda emphasis: prioritising some issues over others to signal commitment (e.g., focusing on job creation, public safety, climate, or cost of living).

Policy reframing: keeping similar goals but changing the rationale (e.g., promoting education spending as economic competitiveness).

Incremental repositioning: gradual movement to avoid alienating existing supporters.

Selective ambiguity: using broad language to hold together groups with differing preferences.

Policy adaptation is constrained by:

Party activists and donors who influence which policy shifts are acceptable.

Elected officials’ records that limit credibility if a shift looks purely opportunistic.

Primary electorates that can reward ideological purity over broad appeal.

Coalition trade-offs

When parties court a new demographic bloc, they risk alienating parts of the existing coalition. Strategic choices often involve:

expanding the coalition (adding groups),

intensifying loyalty among core groups (deepening support),

or targeting high-turnout groups over low-turnout groups.

Messaging adaptation: changing how the party communicates

Even without major policy change, parties can adjust messaging to connect with demographic groups’ values, experiences, and identities. Messaging affects persuasion and turnout by shaping how voters interpret issues and candidates.

Targeted messaging: Tailoring campaign communication to specific audiences using group-relevant language, symbols, and media channels to increase support or turnout.

Parties use messaging to answer: “What does this party mean for people like me?”

Tools of demographic-targeted messaging

Issue framing: presenting policies through lenses that resonate with the group (fairness, freedom, security, opportunity).

Identity cues: highlighting shared background, community ties, or lived experience of candidates and surrogates.

Symbolic politics: emphasising cultural signals (holidays, traditions, national identity, community institutions).

Microtargeting: using voter data to deliver different ads to different groups, often through digital platforms and localised outreach.

Language choice: multilingual materials and culturally competent communication to reduce barriers and build trust.

Mobilisation vs. persuasion

Demographic strategies usually mix:

Mobilisation: increasing turnout among likely supporters (registration drives, community events, “get out the vote” operations).

Persuasion: shifting opinions among swing or cross-pressured voters within a demographic category.

Measuring coalition success

Parties evaluate whether policy and messaging changes are working by tracking:

Vote share shifts within demographic groups across elections

Turnout changes among targeted communities

Party identification trends (longer-term alignment)

Geographic performance where key groups are concentrated

Because demographics intersect (e.g., age and education; race and religion), coalition-building often requires balancing multiple, overlapping audiences without creating contradictory signals that reduce credibility.

FAQ

They weigh electoral math and opportunity.

Size and growth of the group

Turnout likelihood

Concentration in competitive states/districts

How persuadable the group is given current issues and candidates

Symbolic outreach focuses on visibility and recognition (visits, slogans, cultural cues).

Substantive representation involves policy follow-through (legislation, appointments, budgeting) that materially affects the group’s interests.

Mobilisation messages often energise committed supporters using strong identity and moral language.

Persuasion usually requires broader, less polarising framing; highly charged appeals can push swing voters away even as they excite the base.

They may use broad platform language, prioritise shared “umbrella” issues, sequence policy promises, or rely on coalition “brokers” (leaders, interest group allies, trusted local figures) to reduce conflict.

Parties often recruit candidates and campaign staff who signal credibility with target communities (background, language skills, local ties). They may also select surrogates and advisers to improve cultural competence and reduce messaging mistakes.

Practice Questions

Explain what it means for a political party to “build a demographic coalition” through policy and messaging. (3 marks)

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes a demographic coalition as a mix of social groups supporting a party.

1 mark: Explains policy adjustment (changing priorities/positions) to appeal to a group.

1 mark: Explains messaging adjustment (framing/targeted communication) to attract or mobilise a group.

Analyse how adjusting policy and messaging can help a major party win elections, and evaluate one risk of this strategy. (6 marks)

2 marks: Analysis of policy shifts attracting/retaining demographic groups (clear link to votes/turnout).

2 marks: Analysis of messaging (framing/targeting) improving mobilisation or persuasion among demographics.

1 mark: Evaluation of a risk (e.g., alienating existing supporters, credibility problems, internal conflict).

1 mark: Explains how the risk can reduce electoral support (lower turnout, defections, factional splits).