AP Syllabus focus:

‘Interest groups may file amicus curiae briefs—“friend of the court” documents—to provide information for justices reviewing a case.’

Amicus briefs are a major pathway for interest groups to shape how courts understand facts, policy consequences, and legal doctrine. They help translate organised interests into arguments that may influence judicial reasoning.

The role of amicus curiae briefs in U.S. courts

Core idea

Interest groups cannot always appear as parties in a case, but they can still try to influence outcomes by supplying judges with additional perspectives, expertise, and proposed legal rules. This is most visible at the U.S. Supreme Court, where many cases attract dozens of outside briefs.

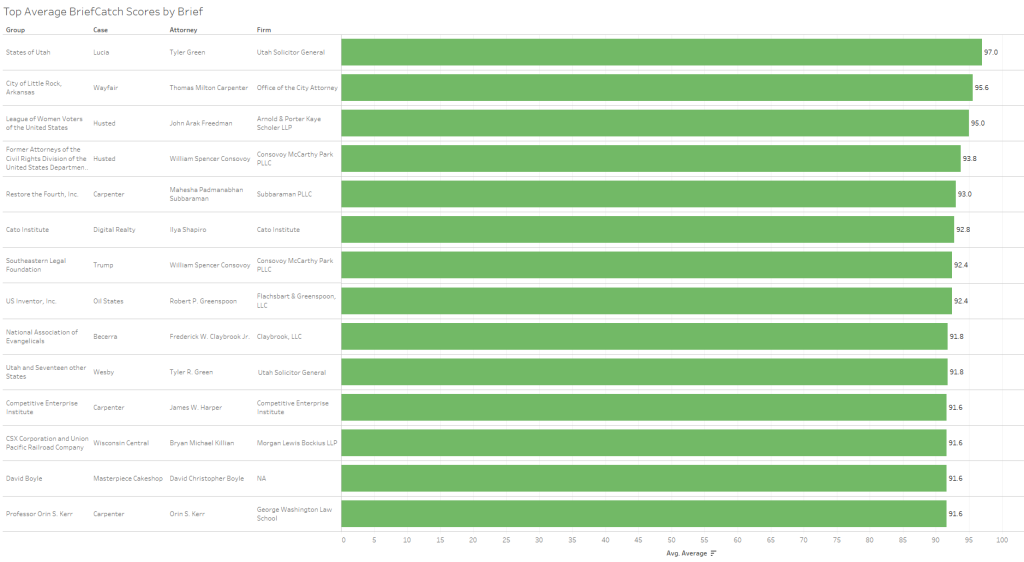

Chart from an Empirical SCOTUS/SCOTUSblog post visualizing the distribution of scores across a large set of Supreme Court merits-stage amicus briefs (2017 Term dataset). It helps students see that amicus practice is “high-volume” and competitive—conditions that can shape how clerks and justices allocate attention to outside briefs. Source

Amicus curiae brief: A written submission by a non-party (“friend of the court”) that offers legal arguments, factual context, or policy information to help a judge decide a case.

Amicus briefs are not evidence in the trial sense; they are arguments and supporting materials intended to frame how the court interprets the Constitution, statutes, precedent, and the broader consequences of a ruling.

Cover page of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure (FRAP) pamphlet (December 1, 2024 edition). In practice, amicus curiae briefing is shaped not only by advocacy goals but also by formal appellate rules governing filing requirements, timing, and format. Source

What interest groups put into an amicus brief

Types of information courts may receive

Interest groups often tailor amicus briefs to the court’s needs by providing:

Legal analysis: suggested interpretations of constitutional text, statutes, or administrative law

Precedent framing: which prior cases should control, and how they should be read

Institutional or technical expertise: industry practices, medical/scientific context, national security considerations, or election administration details

Policy consequences: predicted effects on governance, rights, markets, or public services if the court adopts a particular rule

Signals of broader stakes: showing that the outcome matters beyond the immediate parties (for example, to governments, professions, or affected communities)

Why this matters to judges

Appellate judges (especially Supreme Court justices) decide cases primarily through legal interpretation. Amicus briefs can shape that interpretive environment by clarifying complex domains, offering workable doctrinal tests, and highlighting unintended consequences of broad rulings.

Strategic use by interest groups

Goals beyond “winning” a single case

Interest groups use amicus briefs to pursue long-term policy goals through the courts, such as:

Shaping legal doctrine: advocating a rule that can be used in future litigation

Building a litigation narrative: reinforcing an issue frame (rights-based, federalism-based, public-safety-based, etc.)

Coalition building: filing jointly or coordinating messaging across multiple briefs to show breadth of support

Agenda signalling: demonstrating to members, donors, and allied officials that the group is active and influential

Providing a “menu” of arguments: giving justices multiple rationales to choose from (narrow vs. broad grounds)

Timing and targeting

Most amicus briefs appear at the appellate level, where legal questions (not witness disputes) are central. Groups also target cases likely to set nationwide precedent, where a small number of justices can produce large policy effects.

How courts may use amicus briefs

Pathways of influence

Amicus briefs can matter when they:

Introduce a distinctive argument not fully developed by the parties

Supply credible, high-quality information that helps the court understand real-world operations

Offer limiting principles that help a justice craft a narrower ruling

Support legitimacy by showing that respected institutions or broad coalitions endorse a position

Justices and their clerks may cite amicus briefs directly in opinions, adopt their proposed tests, or use them to evaluate the downstream implications of competing holdings.

Limits, rules, and controversies

Constraints

Amicus briefs are constrained by procedural rules (page limits, filing deadlines, consent requirements in some courts) and by the court’s preference for legally relevant material. A brief that reads like pure political messaging is less useful to judicial decision-making.

Common concerns

Unequal access: well-funded interests can file more (and more polished) briefs than under-resourced groups

Information quality: selective data, questionable social science, or biased “facts” can mislead

Backdoor lobbying: critics argue that heavy amicus activity resembles lobbying of the judiciary, raising transparency and fairness concerns

Overload: a flood of briefs can burden clerks and may privilege repeat-player organisations familiar with court culture

These tensions connect directly to the syllabus emphasis on interest groups leveraging legal processes to influence policy outcomes through courts.

FAQ

Most filings require consent of the parties or leave (permission) of the Court.

Certain governmental actors (e.g., the United States via the Solicitor General) have special standing in practice and are treated with particular attention.

Clerks typically triage by credibility and usefulness, prioritising repeat, reputable filers and briefs offering novel legal tests or high-quality technical context.

They may extract key points into bench memos rather than reading every page closely.

Research findings are mixed: briefs often correlate with salience and coalition strength, which complicates causation.

They may be more influential on the reasoning and scope of a decision than on the final vote count.

Yes. Lower courts often have fewer filings and may apply tighter practical screening.

Because Supreme Court decisions set nationwide precedent, groups concentrate resources there, increasing volume and strategic coordination.

Supreme Court rules require disclosure statements, including whether a party’s counsel authored the brief in whole or part and whether funders contributed.

These disclosures aim to reduce hidden coordination, though critics argue transparency can still be incomplete.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (3 marks) Define an amicus curiae brief and explain one way an interest group might use it to influence justices.

1 mark: Accurate definition of an amicus curiae brief as a submission by a non-party (“friend of the court”).

1 mark: Identifies a valid influence mechanism (e.g., providing legal argument, expertise, policy consequences).

1 mark: Links the mechanism to judicial decision-making (e.g., shaping interpretation, offering a test, framing precedent).

Question 2 (6 marks) Analyse how amicus curiae briefs can affect Supreme Court policymaking. In your answer, include one benefit and one criticism of interest group involvement through amicus briefs.

2 marks: Explains at least two distinct ways briefs can affect outcomes (e.g., framing precedent, supplying expertise, proposing doctrinal tests, signalling broader stakes).

2 marks: Develops analysis of policymaking impact (e.g., precedent-setting rules influencing future cases/nationwide policy).

1 mark: Provides a clear benefit (e.g., better-informed rulings; technical clarity; workable limits).

1 mark: Provides a clear criticism (e.g., unequal influence; biased information; perception of judicial lobbying; overload).