AP Syllabus focus:

‘Unequal resources affect interest group influence; some groups have large memberships, can mobilize them, and have substantial financial reserves.’

Interest groups vary widely in what they can spend, who they can reach, and how quickly they can act. These resource gaps shape which interests are heard most often and most effectively in policymaking.

Core idea: resources create unequal influence

Resource inequality matters because US politics rewards organisations that can sustain long-term engagement, respond rapidly to events, and communicate at scale.

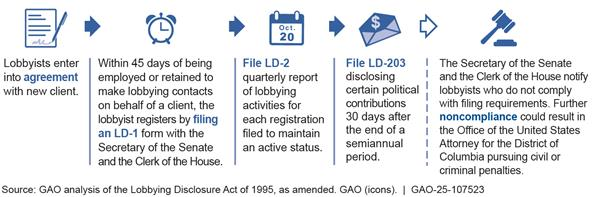

This diagram summarizes the standard federal lobbying disclosure pipeline under the Lobbying Disclosure Act: registration, quarterly activity reporting, semiannual contribution reporting, and the enforcement steps that follow noncompliance. It helps explain why organizational capacity and staff time function as political resources—groups that can reliably manage compliance and reporting are better positioned to maintain a constant presence in policymaking. Source

When some groups have large memberships, can mobilise them, and hold substantial financial reserves, they gain advantages in visibility, persistence, and credibility.

Political resources (what “resources” includes)

Political resources: The assets an interest group can use to pursue policy goals, including money, members, staff expertise, information, organisational capacity, and public legitimacy.

Not all resources substitute for each other; money can buy advertising, but it cannot perfectly replace authentic grassroots pressure or trusted expertise.

Types of resources and how they translate into power

Financial reserves

Groups with substantial financial reserves can:

Maintain permanent staff, offices, and research capacity

Fund sustained outreach and coalition work over multiple election cycles

Absorb setbacks (lost lawsuits, failed bills, reputational hits) without collapsing

Act quickly when a policy window opens (e.g., commissioning reports, launching communications)

Financial depth also supports consistency; policymakers may treat well-funded groups as “always present” stakeholders whose views must be accounted for.

Membership size and mobilisation capacity

Some groups have large memberships and can mobilise them, which can create influence through:

Volume of constituent contacts (calls, emails, town-hall attendance)

Volunteer labour for visibility (rallies, canvassing, community meetings)

Member dues that provide predictable funding

Local chapters that keep issues salient in many districts at once

Mobilisation is most effective when members are geographically and electorally relevant to targeted officials (especially in competitive districts).

Information, expertise, and credibility

Resource inequality also appears in “non-cash” assets:

Policy expertise (law, science, economics) that helps groups produce credible arguments

Data and research capacity to define problems and propose solutions

Professional staff who understand complex rules, deadlines, and institutional procedures

Reputation and legitimacy that makes policymakers and media take claims seriously

Groups that can supply timely, technically accurate information often become repeat participants in policy debates, reinforcing their standing over time.

Organisational capacity and networks

Well-resourced groups tend to have:

Stable leadership and internal coordination (rapid decision-making)

Relationships with allied organisations, donors, and community institutions

Training and communication systems that keep supporters engaged

This “infrastructure” can outperform sporadic activism, especially when policymaking is slow and requires sustained attention.

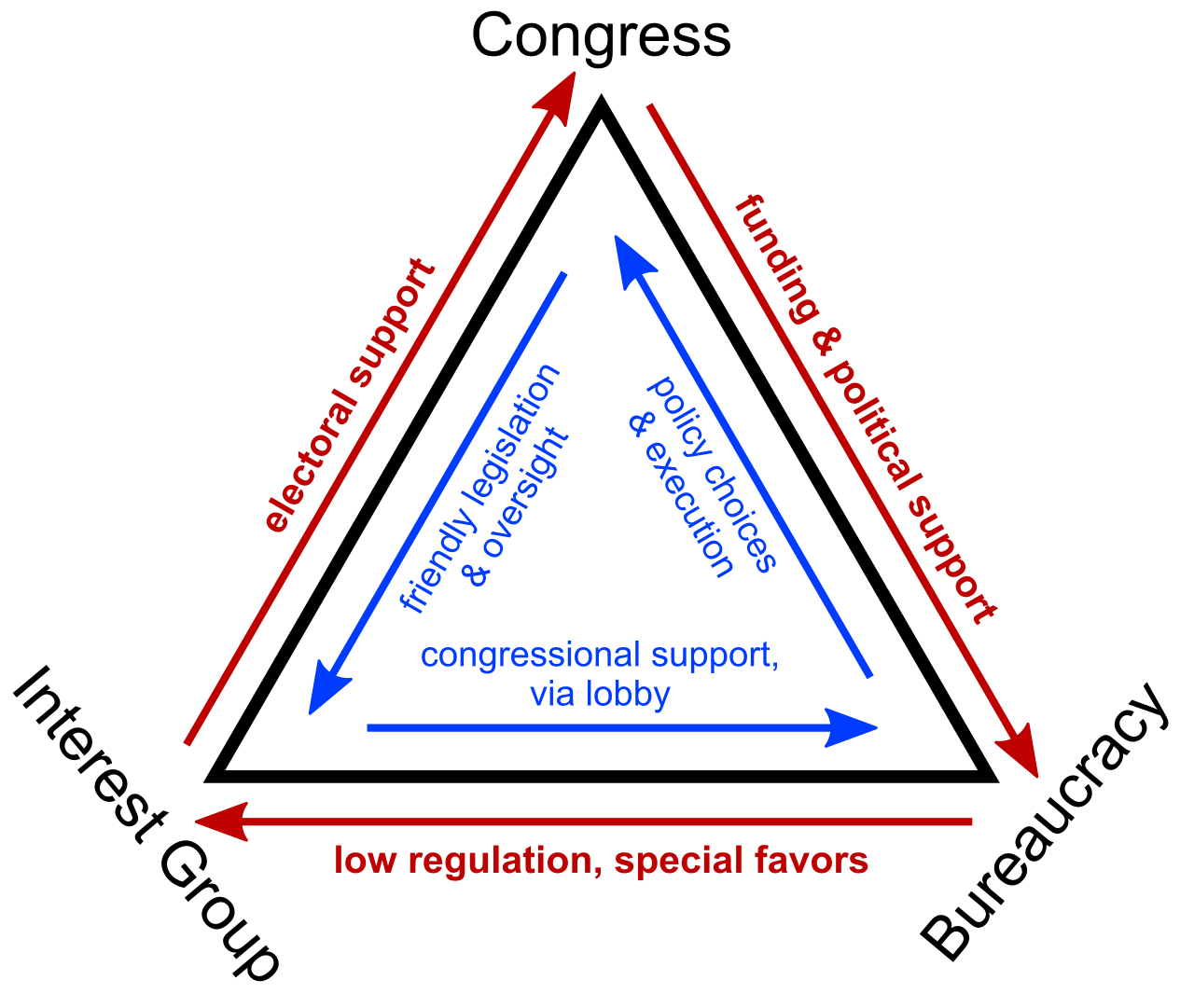

This diagram illustrates the “iron triangle” model: stable, mutually reinforcing relationships among interest groups, congressional committees, and bureaucratic agencies. It’s useful for visualizing how resource-rich groups can convert money, expertise, and mobilization into repeated access, agenda influence, and policy feedback over time. Source

Patterns of inequality: who tends to have more resources?

Resource advantages often correlate with the ability to pay dues, hire staff, or donate:

Business and professional associations may have strong financial bases and specialised expertise.

Broad public-interest or community groups may have moral credibility and committed volunteers but less stable funding.

Some organisations are “member-rich” (many supporters) while others are “resource-rich” (few members, large budgets).

These patterns do not guarantee outcomes, but they affect how consistently and strategically groups can compete.

Democratic implications (why this matters for participation and representation)

Resource inequality can shape which issues receive sustained advocacy and which fade:

Groups with more resources can maintain pressure across the full lifespan of a proposal, not just at moments of public attention.

Less-resourced groups may struggle to keep pace with rapid policy changes or complex technical debates.

If some interests appear more frequently in political arenas, officials may hear a narrower range of perspectives.

At the same time, large memberships can partially counterbalance money when mobilisation signals genuine voter intensity, especially when members are active and well-organised.

FAQ

Common proxies include staff size, number of local chapters, membership counts, member-contact capacity, and the ability to produce policy research.

Some studies also code “organisational maturity,” such as stability of leadership and long-term presence in policy debates.

Influence can come from concentrated expertise, high donor capacity, or strong professional networks.

A smaller group may also have members who are highly engaged, strategically located, or able to provide specialised information quickly.

They can provide large, multi-year grants that stabilise staffing and planning.

Funding priorities can also steer which issues receive sustained organisational support, affecting which interests are continuously represented.

They often focus on low-cost, high-commitment tactics, such as:

Building strong local chapters

Partnering with allied organisations to pool capacity

Developing credible spokespeople and community legitimacy

They may prioritise a narrower set of achievable goals to concentrate effort.

Yes. Communities with less time, money, and institutional support may face higher barriers to forming durable organisations.

This can lead to gaps where some interests are under-organised, even when their policy needs are substantial.

Practice Questions

Explain one way that substantial financial reserves can increase an interest group’s influence. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying a mechanism (e.g., paying staff, running sustained campaigns, commissioning research, rapid response).

1 mark for linking that mechanism to greater influence on policymakers/public debate (e.g., sustained presence, higher visibility, more credible information).

Analyse how unequal resources among interest groups can affect political representation. In your answer, refer to (i) membership mobilisation and (ii) financial reserves. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks: explains how membership mobilisation can affect representation (e.g., constituent pressure, volunteer capacity, local chapters influencing district-level responsiveness).

Up to 2 marks: explains how financial reserves can affect representation (e.g., sustained advocacy, professional expertise, ability to persist through long processes).

Up to 2 marks: analysis of unequal effects on representation (e.g., skewed attention toward resource-rich interests, barriers for low-resource groups, conditional balancing when mobilisation signals high voter intensity).