AP Syllabus focus:

‘Some interest groups have more direct and frequent access to key decision-makers, increasing their ability to influence policymaking.’

Access is a major source of political influence in the United States. This page explains how unequal access to decision-makers develops, where access matters in the policy process, and why it shapes outcomes.

What “access” means in policymaking

Access refers to opportunities to communicate with, advise, and build relationships with key decision-makers (elected officials, senior staff, and high-level administrators) at moments when policy is being shaped.

Access: The ability of an individual or organised group to obtain direct, repeated contact with government decision-makers in order to provide information, request action, or shape policy choices.

Access is not identical to “winning.” It increases the chances an interest group’s preferences are heard, taken seriously, and incorporated into policy design or enforcement.

Why some groups get more direct and frequent access

Decision-makers value information and capacity

Policymakers face time constraints and technical complexity, so they often prioritise groups that can provide:

Policy expertise (data, legal analysis, industry knowledge)

Political intelligence (what affected constituencies want; how a proposal will play publicly)

Implementation capacity (ability to help agencies understand real-world effects)

Credibility, relationships, and “insider” status

Groups with long-standing reputations or consistent engagement can become trusted repeat players. Frequent access often reflects:

Established networks with offices and committees

Professional staff who know procedures and deadlines

Reliability (accurate information; willingness to negotiate)

Institutional gatekeepers concentrate access

Many access points are controlled by gatekeepers who decide which voices reach the top:

Committee chairs and party leaders decide what advances

Legislative staff filter meetings and draft options for members

Agency leadership controls regulatory priorities and enforcement emphasis

Because these gatekeepers have limited time, access tends to cluster around a smaller set of well-resourced, well-connected organisations.

Where access matters in the policy process

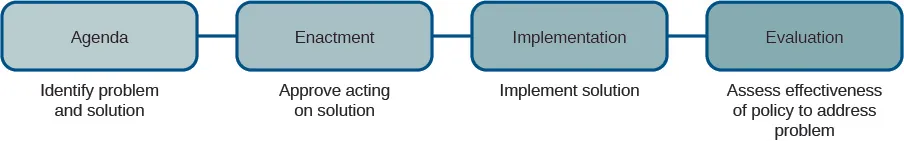

This diagram summarizes the policy process as a sequence of agenda setting, enactment, implementation, and evaluation. It helps show where access and repeated contact with decision-makers can matter most—especially during agenda definition and during implementation when agencies translate broad laws into operational practice. Source

Agenda setting (getting attention)

Groups with strong access can elevate issues by persuading officials that a problem is urgent, politically salient, or solvable. This can determine:

Whether an issue is taken up at all

Which version of the problem becomes “official” (public health vs. cost vs. rights)

Policy design and drafting (shaping the details)

Even when broad goals are agreed upon, details determine winners and losers. Access matters when:

Options are narrowed to a few feasible alternatives

Technical definitions, thresholds, and timelines are chosen

Exceptions and exemptions are negotiated

Adoption and negotiation (securing support)

Access helps groups monitor moving parts and respond quickly as proposals change. Direct contact can:

Signal what compromises will attract or repel key blocs

Provide timely talking points and supporting evidence

Coordinate with allies to stabilise a coalition

Implementation and rulemaking (how policy operates in practice)

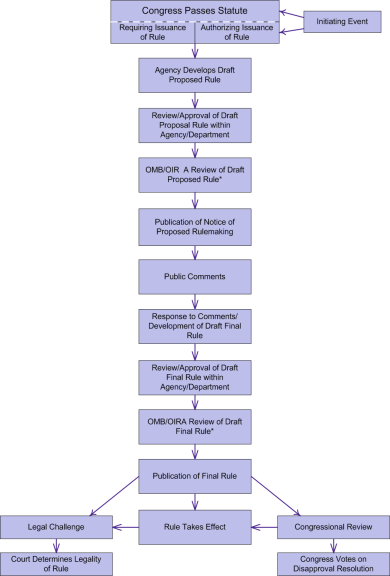

This flowchart outlines the typical federal rulemaking pathway, including drafting a proposed rule, publishing it for public comment, responding to comments, and issuing a final rule. It also highlights external checks—OMB/OIRA review (for significant rules), potential congressional review, and judicial challenges—showing multiple points where organized groups can try to influence details and timelines. Source

After a law passes, agencies interpret it through rules, guidance, and enforcement priorities. Groups with access can:

Clarify operational impacts for administrators

Push for strict or flexible enforcement

Influence compliance expectations and reporting burdens

Oversight and revision (keeping or changing policy)

Access continues after enactment. Ongoing relationships can shape:

How oversight hearings frame success or failure

Whether amendments or administrative adjustments are pursued

Which problems are blamed on policy design versus execution

How unequal access changes policy outcomes

Unequal access tends to create asymmetric influence, where some perspectives are systematically amplified while others struggle to be heard. Common effects include:

Policy bias toward organised, resourced interests with sustained presence

Greater emphasis on technical feasibility and stakeholder acceptability

Increased likelihood that policy includes complex carve-outs that advantage specific sectors

Faster responsiveness to groups that can maintain continuous contact during negotiations

Access can also improve governance when it supplies accurate expertise, highlights implementation problems early, and prevents unintended consequences. The central AP Government tension is that the same mechanism that improves information flow can also produce inequality in representation.

Constraints on access (and why access isn’t everything)

Even highly connected groups face limits:

Competing access: other groups may have equal or greater credibility with the same officials

Public opinion and media attention: visible controversies can make officials avoid certain positions

Institutional rules: ethics rules, transparency requirements, and procedural timelines can restrict contacts

Partisan and electoral incentives: officials may discount access requests that threaten coalition unity or reelection goals

Access is best understood as an advantage that affects what is considered, how it is written, and how it is carried out—especially when officials must choose among competing demands under time pressure.

FAQ

Rules may limit gifts, require disclosures, or restrict certain contacts, but they rarely prevent meetings or information-sharing.

They often shift access towards formal channels (scheduled meetings, written submissions) rather than ending access altogether.

Staff screen requests, summarise arguments, and recommend options, so access to staff can shape what the member ever sees.

Staff also track deadlines and procedural pathways, making them key gatekeepers for timely influence.

Yes. Specialised technical knowledge can make a small group valuable to offices facing complex policy choices.

Credible data, legal arguments, and implementation know-how can substitute for sheer size in earning repeat contact.

Congressional access often centres on committee leadership and staff, especially during negotiation and scheduling.

Agency access often matters most during rule interpretation and enforcement, where technical detail and compliance realities are central.

They can broaden consultation by inviting diverse stakeholders, using open comment processes, and relying on independent expert sources.

They can also increase transparency around meetings and rationales to deter one-sided influence.

Practice Questions

Explain one way that more frequent access to key decision-makers can increase an interest group’s influence in the policy process. (2 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid mechanism (e.g., repeated meetings with senior staff/committee members/agencies).

1 mark: Explains how it increases influence (e.g., shapes agenda, alters policy details, affects implementation/enforcement priorities).

Analyse how unequal access to decision-makers can shape policy outcomes at two different stages of the policy process. (5 marks)

1 mark: Identifies one stage (e.g., agenda setting, drafting, implementation, oversight).

1 mark: Explains an access-based effect at that stage.

1 mark: Identifies a second, different stage.

1 mark: Explains an access-based effect at the second stage.

1 mark: Provides analysis linking unequal access to broader consequences (e.g., policy bias, carve-outs, under-representation), not just description.