AP Syllabus focus:

‘Single-issue groups and ideological or social movements form with the goal of affecting society and shaping policymaking.’

Single-issue groups and social or ideological movements are major pathways for political participation outside elections.

The National Archives’ image of the Bill of Rights emphasizes the constitutional foundation for many forms of participation used by single-issue groups and movements. In practice, tactics like protest, lobbying, and public messaging depend heavily on protections for speech, assembly, and petition. Source

They organise people around shared concerns, pressure decision-makers, and try to change what government prioritises and what policies it adopts.

Core ideas: what these groups are trying to do

Both single-issue groups and social/ideological movements exist to affect society and shape policymaking by changing public debate, influencing officials, and building sustained support for a cause.

Single-issue group: An organisation focused on one public policy area (or a tightly linked set of issues) that seeks to influence government action and public attitudes on that specific concern.

These groups often develop clear policy demands (pass, repeal, or block a law; change a regulation; alter enforcement priorities) and measure success narrowly, such as a court decision, agency rule, or legislative vote.

Social movement: A large, sustained, and collective effort—often involving informal networks and public action—aimed at changing social norms and/or public policy.

Movements are usually broader than a single organisation and can include multiple groups with overlapping goals, ranging from local chapters to national coalitions.

Single-issue groups: structure and strategy

Why single-issue groups form

Single-issue groups commonly form when people believe:

A particular policy area is under threat or neglected

Major parties are not representing the issue strongly enough

Concentrated attention and resources can outperform broader, less focused advocacy

How they shape policymaking

Single-issue groups seek influence by making the issue difficult for officials to ignore:

Information and framing

Provide talking points, research, and narratives that define the problem and preferred solution

Emphasise moral claims, rights-based arguments, or cost-benefit claims, depending on the audience

Mobilisation

Turn sympathisers into consistent participants (calls, emails, meetings, turnout)

Use pledges, scorecards, and endorsements to reward allies and punish opponents

Agenda pressure

Keep the issue visible through events, earned media, and sustained messaging

Push policy “windows” after crises, elections, or court rulings

Organisational advantages and trade-offs

Advantages

Clear mission helps fundraising and recruitment

Narrow goals reduce internal disagreement and simplify messaging

Trade-offs

Risk of “tunnel vision,” ignoring coalition needs or unintended consequences

Harder to broaden appeal if the issue becomes polarised

Social and ideological movements: building change over time

What makes a movement “ideological” or “social”

An ideological movement is organised around a shared worldview (e.g., beliefs about liberty, equality, tradition, or the role of government). A social movement often targets social norms and institutions as well as policy, aiming to change what society views as acceptable or urgent.

How movements grow and sustain themselves

Movements typically develop through:

Collective identity

Shared symbols, language, and stories that create belonging

Networks

Loose coalitions of community groups, faith organisations, student groups, and online communities

Leadership and decentralisation

Some movements rely on charismatic leaders; others use decentralised organising that is resilient but harder to coordinate

Resource building

Volunteers, donors, legal support, and communications capacity that allow sustained activity over years

Movement tactics that affect policymaking

Movements pressure policymakers indirectly and directly:

Public visibility

Marches, boycotts, sit-ins, strikes, and mass meetings to demonstrate intensity and numbers

Norm change

Persuasion campaigns that shift public opinion and make certain policies politically “normal”

Institutional engagement

Pushing for policy commitments from candidates, influencing party platforms, and targeting local and state policy as stepping stones

Counter-mobilisation

Movements often trigger opposing movements, shaping policymaking through competition over attention and legitimacy

Limits and democratic tensions

Efforts to shape policymaking face constraints:

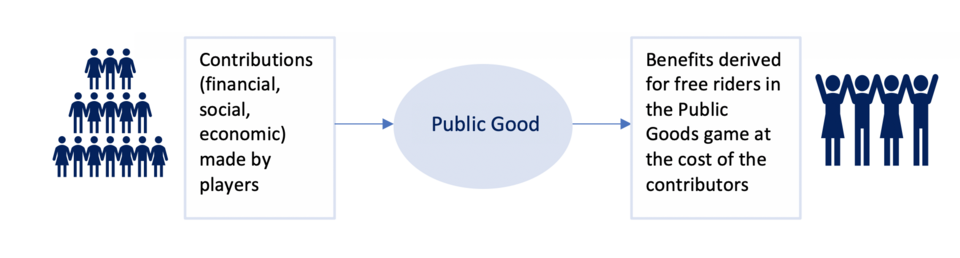

This diagram illustrates free-riding in a public goods game, where some individuals contribute little or nothing while still benefiting from collective outcomes. It’s a useful model for political participation: even if many people support a cause, incentives to “let others do the work” can reduce consistent engagement and limit a group’s influence. Source

Collective action problems

People may agree with a cause but not participate consistently; leaders must convert sympathy into action

Political opportunity structure

Success is more likely when institutions are receptive (close elections, divided government, or sympathetic courts)

Public opinion and backlash

Rapid change efforts can generate backlash that slows or reverses policy gains

Representation concerns

Highly organised minorities can exert outsized influence, raising debates about intensity vs. majority preference in a democracy

FAQ

They weigh urgency, public support, and institutional openness.

Incremental approaches often target local/state rules first.

Transformative approaches prioritise norm change and broad coalitions before legislation.

Decentralisation spreads decision-making across chapters or networks rather than a single hierarchy.

It can increase resilience and participation, but may reduce message discipline and bargaining clarity with policymakers.

They invest in routines and relationships:

Regular meetings and leadership development

Clear roles for volunteers

Small, frequent “wins” that reinforce commitment

Splits occur over strategy, ideology, or leadership disputes.

Effects can include sharper specialisation (helpful) or fragmented messaging and competition for supporters (harmful).

They may track:

Shifts in public opinion and language norms

Growth of local chapters and volunteer retention

Changes in elite behaviour (candidate commitments, institutional practices)

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define a single-issue group and explain one way it can shape policymaking.

1 mark: Accurate definition (group focused on one policy area seeking to influence policy).

1 mark: One explained method (e.g., mobilising supporters to contact legislators; endorsements/scorecards; media framing; lobbying).

(6 marks) Analyse how a social or ideological movement can shape policymaking. In your answer, distinguish it from a single-issue group and refer to at least two movement tactics.

1 mark: Clear distinction (movement = broad, sustained collective effort/network; single-issue group = organisation focused narrowly on one policy area).

2 marks: Explains two tactics (1 mark each) such as protests/boycotts, norm change campaigns, coalition-building, decentralised mobilisation, candidate pressure.

2 marks: Links tactics to policymaking outcomes (agenda-setting, shifting public opinion, increasing costs of inaction for officials, enabling legislation/regulation).

1 mark: Analytical point about conditions/limits (e.g., backlash, political opportunities, collective action problem).