AP Syllabus focus:

‘Protest movements can form to influence society and government by raising attention, pressuring officials, and changing the policy agenda.’

Protest movements are a recurring feature of American politics. They seek to translate public grievance into governmental response by reshaping attention, mobilising supporters, and altering the incentives elected officials face when making policy.

What protest movements are trying to change

Protest movements aim to affect both what government talks about and what government does. Their influence often begins before any law is passed, by shifting how issues are understood and which issues feel urgent.

Policy agenda: The set of problems and proposals that receive serious attention from policymakers and are considered “up for action.”

Because time and political capital are limited, movements compete to elevate their issue onto the policy agenda and keep it there long enough to produce tangible governmental action.

Core pathways from protest to policy change

Raising attention

Movements use visible tactics to increase salience—the perceived importance of an issue to the public and elites.

Public demonstrations (marches, rallies, vigils) create newsworthy moments and signal breadth of support.

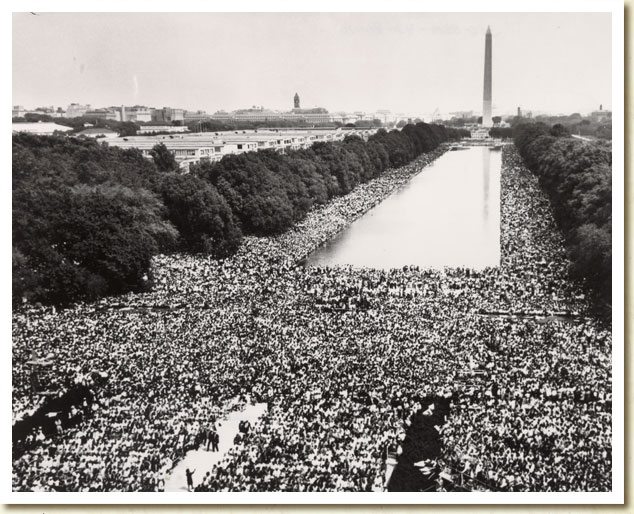

Aerial photograph of the August 28, 1963 March on Washington showing the sheer scale of participation on the National Mall. In agenda-setting terms, large, highly visible demonstrations can increase an issue’s salience by creating newsworthy visuals and signaling broad-based public commitment. The image helps illustrate how movements translate collective grievance into pressure that elected officials cannot easily ignore. Source

Disruption (strikes, boycotts, sit-ins, walkouts) increases the costs of ignoring a problem.

Symbolic action (public art, slogans, coordinated displays) helps simplify complex issues into memorable frames.

Attention can be amplified when protests are sustained, geographically widespread, or tied to compelling narratives that connect personal experience to public policy.

Pressuring officials

Movements convert attention into leverage by changing what officials expect from voters, donors, party activists, and local institutions.

Electoral pressure: signalling that inaction may trigger primary challenges, turnout shifts, or party defection.

Institutional pressure: targeting city councils, school boards, governors, or agencies where smaller constituencies can matter more.

Coalition pressure: working with sympathetic community leaders, professionals, or organised constituencies to strengthen credibility and reach.

Moral pressure: using nonviolent discipline, testimony, and public accountability to make inaction appear illegitimate.

Pressure is most effective when movements can identify specific decision-makers and demand concrete steps, rather than only general expressions of support.

Changing the policy agenda

Agenda change is often the decisive intermediate outcome: once leaders accept a problem as urgent and solvable, proposals become more likely to advance.

Framing: defining the problem and its causes (for example, as a rights issue, a public safety issue, or an economic issue).

Focusing events: high-profile incidents (or widely shared documentation) that concentrate public attention and force officials to respond.

Policy windows: moments when political conditions make change more possible, such as leadership turnover, crises, or shifting public opinion.

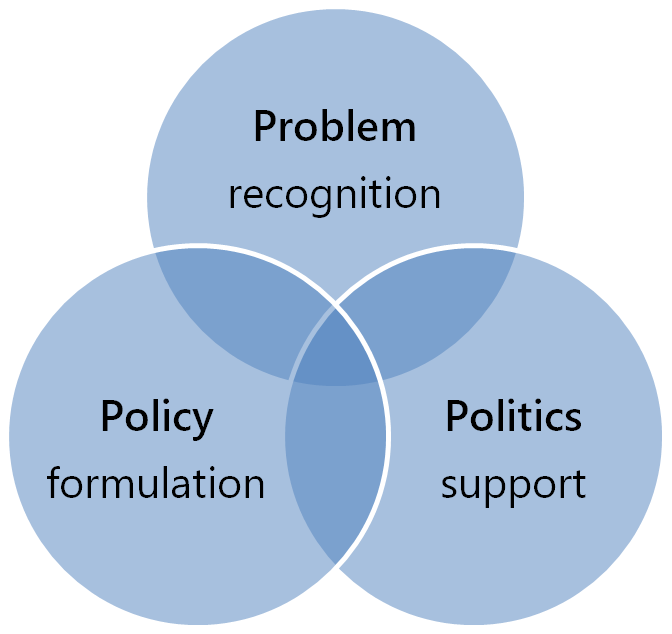

Diagram of the Multiple Streams Framework, showing how the “problem,” “policy,” and “politics” streams can converge to open a “policy window.” This is a standard agenda-setting way to explain why some moments are unusually ripe for policy change: attention to a problem is not enough unless workable proposals and political support align. Use it to connect protest-driven salience and pressure to the specific conditions under which issues move onto the policy agenda and toward adoption. Source

Movements that supply ready-made solutions—draft standards, model rules, or clear administrative actions—can make it easier for officials to act quickly once the agenda shifts.

Protest tactics and how they translate into outcomes

Different tactics are suited to different stages of influence.

Mobilisation tactics build numbers: campus organising, community canvassing, mutual aid, and online recruitment.

Persuasion tactics broaden support: storytelling, expert endorsements, and values-based messaging.

Disruptive tactics raise the costs of delay: work stoppages, consumer boycotts, and coordinated shutdowns.

Negotiation tactics convert pressure into policy: meetings with officials, public hearings, and participation in rulemaking processes.

Policy change can take multiple forms—new legislation, executive directives, agency enforcement priorities, budget allocations, or changes in institutional rules—so movements often pursue several channels at once.

Why some movements succeed and others stall

Protest does not automatically produce policy change; outcomes depend on political conditions and strategic choices.

Conditions that increase impact

Clear objectives and realistic, measurable demands.

Sustained participation rather than one-time events.

Public legitimacy, often strengthened by nonviolent tactics and broad coalitions.

Elite allies inside government who can sponsor proposals and navigate procedure.

Favourable political opportunity, such as competitive elections or divided elites.

Common limits and risks

Counter-mobilisation by opponents can harden resistance or shift the agenda elsewhere.

Repression or restrictive rules (permits, curfews, aggressive policing) can reduce participation and change media narratives.

Message fragmentation can occur when decentralised movements struggle to present consistent demands.

Backlash effects may reduce public sympathy, especially if protests are portrayed as threatening order or economic stability.

How to connect protest to AP Government reasoning

When explaining protest movements and policy change, focus on the syllabus logic: protests raise attention, pressure officials, and change the policy agenda. Then show how agenda change can lead to concrete governmental outputs through elections, legislation, executive action, or administrative implementation.

FAQ

They often track intermediate indicators, such as shifts in media volume, polling on issue salience, elite speeches, committee hearings, agency investigations, or budget proposals.

Longitudinal analysis can compare pre- and post-protest trends, while accounting for other events that might explain change.

It can help when:

rapid mobilisation is needed across many locations

repression targets formal leaders

local groups can tailor tactics to community conditions

The trade-off is usually weaker message discipline and slower negotiation with institutions.

Court rulings can reshape the environment indirectly by changing what policies are legally possible, prompting officials to act to avoid lawsuits, or creating symbolic legitimacy that strengthens bargaining power.

Movements may then pivot to implementation pressure rather than new lawmaking.

They can influence turnout, media framing, and public sympathy. Strict permitting, dispersal orders, or selective enforcement may reduce sustained participation or shift attention from the cause to public order.

In some cases, heavy-handed responses generate sympathy and broaden support.

International coverage can raise reputational costs for officials, affect investor or tourism perceptions, and provide movements with external validation.

It can also provoke nationalist backlash, so its effect depends on domestic political framing and elite cues.

Practice Questions

(3 marks) Identify and briefly describe two ways a protest movement can pressure government officials to act.

1 mark: Identifies one valid way officials are pressured (e.g., electoral threat, disruption, targeting local institutions).

1 mark: Identifies a second valid way.

1 mark: Brief description of how either method changes officials’ incentives (e.g., fear of losing office, increased costs of inaction).

(6 marks) Explain how protest movements can change the policy agenda and lead to policy change. In your answer, analyse two distinct mechanisms and support each with accurate political reasoning.

1 mark: Explains agenda change via raising attention/salience (media coverage, focusing events, sustained visibility).

1 mark: Connects attention to policymakers taking the issue seriously (agenda-setting logic).

1 mark: Explains pressure on officials (electoral incentives, institutional leverage, coalition pressure, moral legitimacy).

1 mark: Connects pressure to a plausible policy response (legislation, executive action, agency enforcement, budgeting).

1 mark: Develops reasoning for mechanism 1 (clear causal chain, not just assertion).

1 mark: Develops reasoning for mechanism 2 (distinct from the first and causally coherent).