AP Syllabus focus:

‘Elections and political parties can be linked to major policy shifts or initiatives and may lead to realignments in voting constituencies.’

Elections connect public preferences to governing power. When parties win control of institutions, they can enact major policy initiatives, reshape agendas, and sometimes shift which social groups consistently support each party.

How elections translate into policy change

Party control and governing capacity

Major policy shifts are most likely when an election changes party control of key institutions or expands a party’s majority.

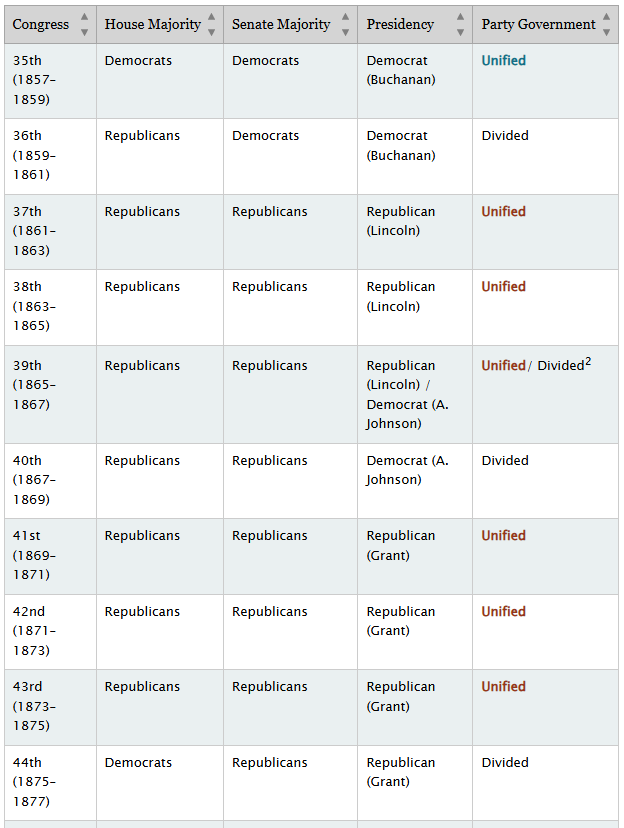

This table tracks party control of the presidency, the House, and the Senate by Congress, and explicitly labels periods of unified versus divided government. It visually reinforces why unified control tends to increase agenda-setting leverage and why divided control often increases bargaining and veto points. Using a time series also helps illustrate how shifts in control can coincide with durable changes in party coalitions. Source

Unified government (one party controls the presidency and both chambers of Congress) generally increases the chances of passing a party’s priorities.

Divided government often produces incremental change, compromises, or policymaking through budgeting and oversight rather than sweeping statutes.

Close margins empower pivotal legislators (e.g., moderates, committee chairs) who can demand policy concessions.

Elections, agendas, and “what government works on”

Elections can reset political attention and define which problems get treated as urgent.

Parties use campaigns to elevate certain issues; victory can be read as public support for addressing those issues first.

Control of congressional committees and leadership affects which bills get hearings, votes, and floor time.

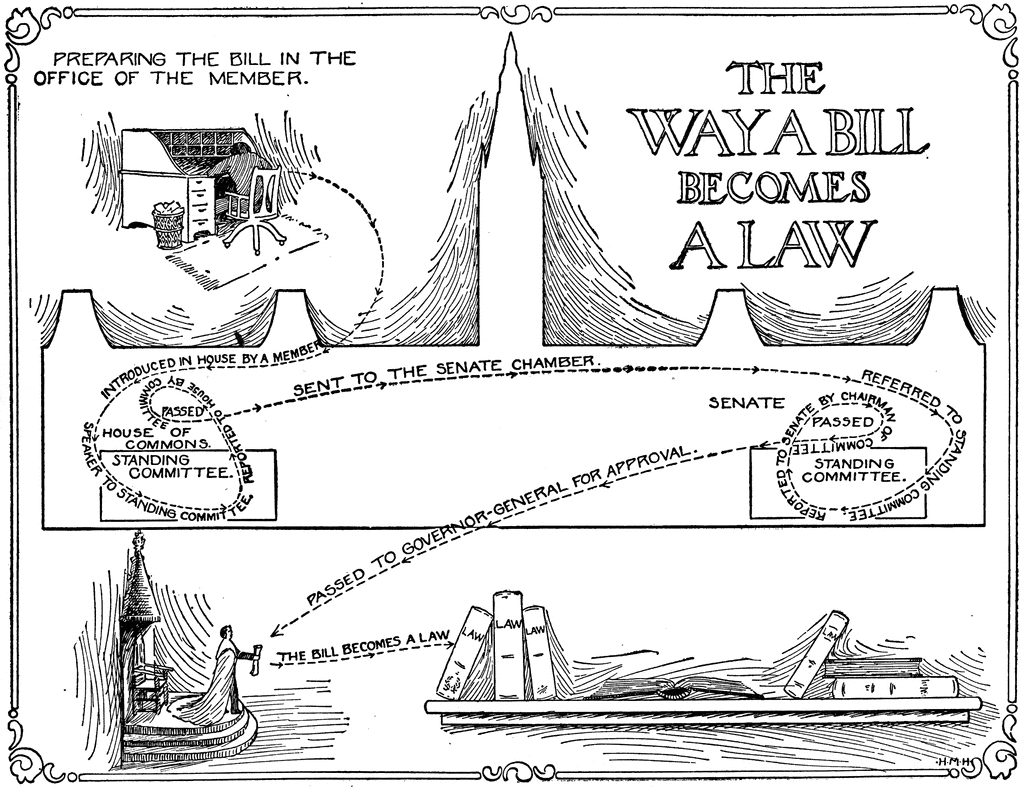

This flowchart summarizes the major procedural stages a bill typically moves through on its way to becoming law, from introduction through committee consideration and final approval. It supports the idea that party leadership and committee gatekeeping can accelerate, stall, or reshape proposals before they ever reach a decisive vote. Seeing the steps as a process diagram clarifies where agenda control and pivotal actors can matter most. Source

Even without new laws, elections can shift priorities in implementation through appointments and administrative direction (especially in the executive branch).

Policy “mandates” and legitimacy

Winning candidates and parties often claim that electoral victory provides authority to pursue specific initiatives.

Mandate: A perceived authorisation from voters that an election winner (or party) uses to justify implementing promised policies.

A mandate is politically powerful but not automatic; opponents may argue voters supported a candidate for other reasons (economy, personality, partisanship), limiting how clearly the election signals policy approval.

Political parties as engines of major initiatives

Parties package policy choices

Parties help convert broad public demands into concrete proposals.

Party leaders coordinate messaging so individual races reinforce a national policy agenda.

Parties simplify choices for voters by bundling positions into identifiable programs (e.g., taxes, healthcare, regulation).

Parties organise action after the election

Once in office, parties can drive policy by:

Setting legislative priorities through leadership and committee systems

Whipping votes to maintain party unity on key bills

Negotiating internally to balance factions while still producing a coherent policy direction

How major policy shifts can reshape voting constituencies

Realignments as changes in durable party support

The syllabus notes that elections and parties “may lead to realignments in voting constituencies.” In practice, major policy shifts can alter which groups feel represented by each party.

New policies create winners and losers (materially or symbolically), changing group attachments over time.

Parties may attract new supporters by emphasising policies that resonate with emerging concerns (jobs, rights, security, cultural issues).

Group movement is often gradual: repeated elections reinforce a new pattern of loyalty rather than a one-time switch.

Coalitions and feedback effects

Policies can generate long-term political feedback.

Beneficiaries may become more politically active to defend a program.

Costs or disruptions can mobilise opposition groups.

Party labels become associated with policy outcomes, shaping how constituencies evaluate future candidates from each party.

Limits and conditions on election-driven policy change

Institutional and political constraints

Even after a decisive election, major change is not guaranteed.

The filibuster (Senate) and narrow majorities can block or dilute ambitious proposals.

Courts can limit or reshape implementation when policies face constitutional challenges.

Federalism means states can cooperate with, resist, or reinterpret national initiatives.

Interpreting election results is contested

Parties strategically frame victories as policy endorsements, while opponents argue:

Turnout patterns may reflect mobilisation differences rather than broad agreement.

Voters may prioritise party identity over specific policies.

A win in a winner-take-all system can overstate consensus in closely divided electorates.

FAQ

They typically prioritise proposals that are most unifying within the party and most feasible procedurally.

Key influences include:

Leadership strategy and committee gatekeeping

Time constraints (e.g., early “honeymoon” period)

Bargaining to satisfy internal factions while keeping a majority

It is stronger when victory is clear and the winning side can plausibly tie the result to a specific issue.

Signals can include:

Large popular-vote margin (where applicable) and sizeable congressional gains

Consistent issue emphasis during the campaign

Post-election public opinion showing agreement on the initiative

Yes. Policies can impose concentrated costs or spark backlash, especially if implementation is disruptive.

This can:

Energise opposition turnout

Split the governing party’s factions

Rebrand the party around a controversial outcome

Coalitions can change through differential turnout, group mobilisation, and generational replacement rather than persuasion.

For example:

One group becomes more likely to vote consistently

Another disengages or reduces participation

Younger voters enter with different baseline loyalties

They reinforce credit-claiming and identity ties to the policy.

Common tactics:

Emphasising tangible benefits and symbolic wins in messaging

Building allied organisations and networks that mobilise supporters

Defending or expanding the policy to keep beneficiaries engaged

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one way an election can be linked to a major policy shift.

1 mark: Identifies a valid link (e.g., unified government enables passing legislation).

1 mark: Explains how that link produces policy change (e.g., party leadership controls agenda and can coordinate votes to enact an initiative).

(6 marks) Analyse how a political party’s election victory could lead to both (a) a major policy initiative and (b) a realignment in voting constituencies.

2 marks: Explains mechanisms producing a major initiative (e.g., control of institutions, agenda-setting, party discipline, committee leadership).

2 marks: Connects enacted policy to shifting group support (e.g., beneficiaries align with the party; adversely affected groups defect).

1 mark: Notes durability/feedback (changes reinforced across subsequent elections through mobilisation or identity).

1 mark: Includes a relevant constraint or qualification (e.g., filibuster, courts, federalism, narrow mandate).