AP Syllabus focus:

‘Democratic and republican ideals inspired new governments, rights protections, and debates over power, while also prompting challenges to inequality in society.’

Revolutionary ideals transformed political expectations in the new United States, inspiring experiments in governance, protections for individual rights, and growing debates over power, representation, and persistent social inequalities.

Revolutionary Principles and the Reimagining of Government

Enlightenment Foundations of Political Change

Revolutionary-era Americans drew heavily from Enlightenment political philosophy, which emphasized reason, natural rights, and the legitimacy of government based on the consent of the governed. These concepts shaped debates about how to construct governments that promoted liberty while preventing tyranny. Revolutionary leaders believed that sovereignty ultimately rested with the people, and that governments existed to protect essential liberties such as life, liberty, and property. As a result, the post-Revolution moment became a laboratory for testing new structures of political authority.

Republicanism as a Guiding Framework

The new nation embraced republicanism, an ideology asserting that citizens should elect representatives to govern on their behalf. Republicanism placed a high value on civic virtue and the moral responsibility of citizens, who were expected to act for the common good rather than purely personal interest.

Republicanism: A political ideology emphasizing representative government, popular sovereignty, and civic virtue as foundations of a free society.

Republican ideals encouraged the creation of governments that limited executive power, distributed authority broadly, and relied on the active participation of politically engaged citizens.

A renewed emphasis on virtue supported fears that concentrated power would threaten liberty. Americans therefore designed governments that dispersed authority through elected assemblies, written constitutions, and clearly defined rights.

Written Constitutions and Governmental Experiments

State Constitutions as Testing Grounds

After independence, each state drafted its own constitution, providing early experiments in representative government. These state constitutions commonly featured:

Written frameworks outlining laws and governmental structures

Powerful legislatures reflecting distrust of strong executives

Declarations of rights protecting freedoms such as trial by jury, freedom of the press, and protection against arbitrary government

Many states maintained property qualifications for voting, demonstrating the tension between egalitarian ideals and longstanding beliefs about the relationship between property ownership and civic responsibility. State constitutions varied widely, revealing intense debates about how to balance liberty with stability.

Advocating for Rights Protections

Revolutionary ideals also spurred widespread belief that governments must explicitly safeguard individual liberties. This belief prompted the adoption of bills of rights in many state constitutions and eventually helped shape the national Bill of Rights under the new federal government.

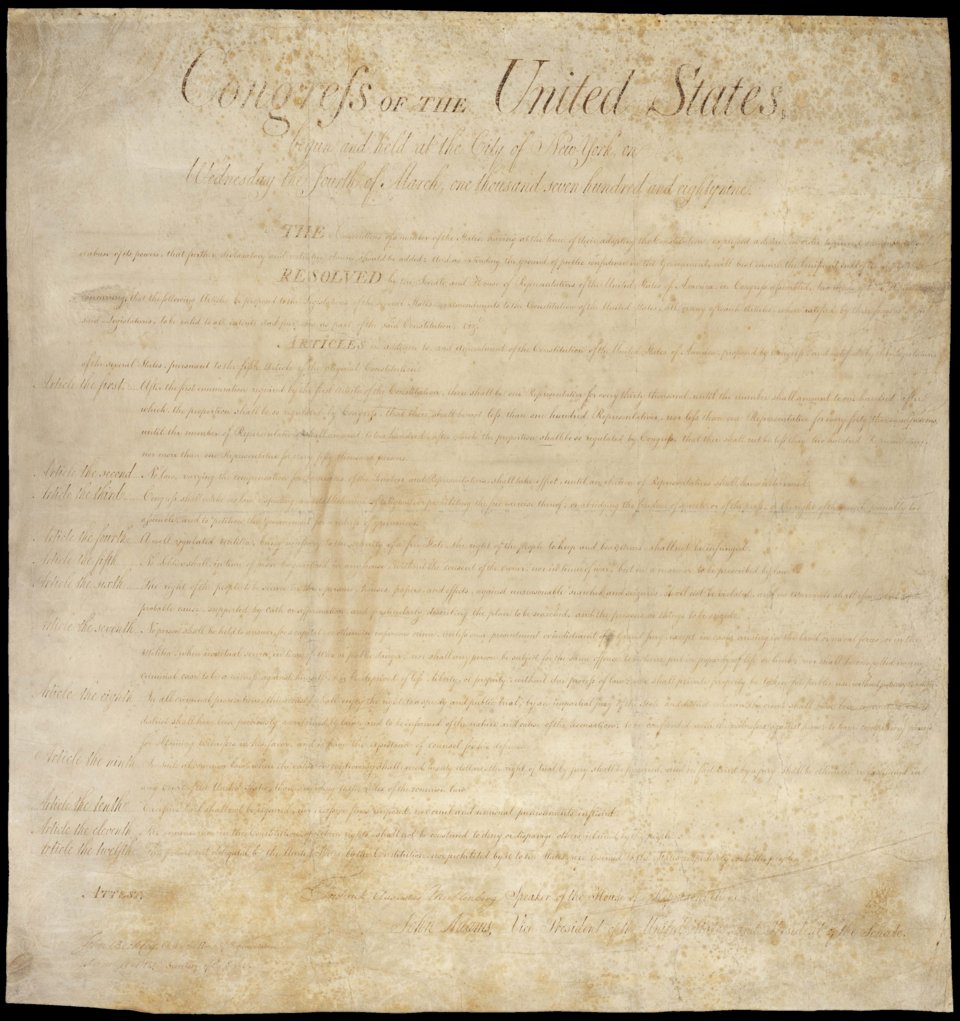

This document is a high-resolution image of the original U.S. Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution. It illustrates how revolutionary concerns about individual liberties were translated into written protections against federal power. The image includes the full text of the amendments, which goes beyond what students must memorize but reinforces the idea that rights were concretely defined in law rather than left to custom alone. Source.

These documents codified protections such as:

Freedom of speech and religion

Rights of the accused

Limits on governmental power

These protections were rooted in the Revolution’s emphasis on defending natural rights against potential governmental overreach.

Debates Over Political Power and Participation

Expanding and Limiting Political Inclusion

While Revolutionary thought celebrated universal natural rights, political rights were not universally extended. Debates emerged over who should participate in government and to what degree. Key tensions included:

Maintaining property requirements versus expanding political participation

Balancing majority rule with protections for minority rights

Determining the appropriate strength of local versus central authority

These disputes revealed Americans’ struggles to reconcile egalitarian ideals with concerns about maintaining social order and preventing what some feared would be excessive democracy.

Challenges to Social Inequality

Revolutionary language about equality prompted several groups to advocate for expanded rights and greater fairness within society. Inspired by the Revolution’s promise of liberty, reformers questioned hierarchies based on race, gender, and class. Such challenges included:

Debates about slavery and the morality of human bondage

Increased calls for women’s rights, particularly in education

Efforts to reduce practices that reinforced rigid social privilege

Although significant inequalities persisted, the post-Revolution period marked the beginning of broader national conversations about who should benefit from the Revolution’s ideals.

Slavery, Freedom, and Revolutionary Tensions

Growing Antislavery Sentiment

Revolutionary arguments about natural rights generated antislavery activism, especially in the North. African Americans and white abolitionists used the Revolution’s own rhetoric to highlight the contradiction between liberty and slavery.

This antislavery medallion shows an enslaved man in chains kneeling beneath the inscription “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?”. It visually expresses the revolutionary claim that all people share a common humanity and therefore natural rights, directly challenging racial slavery. The medallion comes from a British abolitionist campaign, which adds extra detail beyond the syllabus but still illustrates how revolutionary ideas about liberty fueled wider antislavery activism. Source.

Movements emerged to:

Petition state legislatures for emancipation

Challenge racial hierarchies in court

Create free Black communities centered on institutions such as churches and mutual aid societies

These efforts pressured states to reconsider slavery, leading to gradual emancipation laws in several northern states.

Persistence of Inequality and Contradiction

Despite antislavery efforts, the institution expanded in the South. Many enslavers defended slavery as compatible with republicanism, claiming it protected social order and property rights. The coexistence of abolitionist ideals and intensified slaveholding underscored the Revolution’s unresolved contradictions.

Women, Citizenship, and Political Culture

Influence of Republican Ideals on Women

Women used Revolutionary rhetoric to advocate for increased educational opportunities and a stronger role in shaping civic values. Their participation in homes, communities, and wartime support networks reinforced arguments that women were essential to sustaining the nation’s republican character.

Republican Motherhood: The belief that women, as mothers and educators of future citizens, held an important civic responsibility to cultivate republican virtue.

This ideal enhanced women’s cultural and political significance, even as they remained excluded from formal political participation.

James Peale’s “The Artist and His Family” presents a late-18th-century household in which the mother appears prominently alongside her husband and children. The painting reflects the ideology of republican motherhood, in which women were expected to nurture virtue and patriotism in the next generation, giving them a crucial, though indirect, political role. The landscape setting and details of family life exceed the syllabus but help visualize the social world in which ideas about gender and citizenship took shape. Source.

Shifting Cultural Expectations

By placing value on women’s intellectual and moral influence, Revolutionary ideals slowly expanded acceptable roles for women in American society. Increased literacy, educational institutions for girls, and new discussions of female capability reflected the Revolution’s long-term social effects.

Revolutionary Ideals and Enduring Debates

Revolutionary commitments to liberty, equality, and self-government created ongoing national debates about how to balance power, rights, and inclusion. These early struggles laid the groundwork for later reform movements and continued attempts to translate the Revolution’s promises into social and political reality.

FAQ

Popular sovereignty expanded from a general claim that authority originated with the people to a practical principle guiding constitutional design. Early Americans increasingly insisted that governments must derive legitimacy from written constitutions drafted by elected delegates rather than inherited authority.

This shift elevated the role of constitutional conventions and encouraged the belief that political frameworks should be deliberately created, not merely accepted as tradition.

While revolutionary rhetoric stressed equality, many elites feared that broad democratic participation could destabilise the new republic. Property requirements for voting and officeholding were therefore defended as safeguards against the political influence of those seen as lacking independence.

Working-class Americans, however, used revolutionary language to challenge these limits and argue that political rights should not depend solely on wealth.

Many Americans interpreted revolutionary ideals through a religious lens, arguing that natural rights were part of a moral order established by God. This belief strengthened demands for liberty of conscience and contributed to expanded protections for religious freedom.

Some reformers also used religious arguments to criticise slavery and hierarchical authority, blending spiritual and political reasoning.

Free Black Americans drew directly on the language of equality and natural rights to petition legislatures, establish mutual aid societies, and build autonomous institutions such as churches.

Their activism aimed to demonstrate civic virtue and challenge discriminatory laws, asserting that African Americans were entitled to the same liberties proclaimed during the Revolution.

The belief that a republic could survive only if its citizens possessed civic virtue shaped political culture after independence. Virtue was linked to self-discipline, public-spiritedness, and resistance to corruption.

These expectations informed debates about education, character formation, and the moral responsibilities of both voters and public officials, including the argument that women helped preserve virtue within families.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which revolutionary ideals influenced the creation of early American state constitutions.

Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying a valid influence of revolutionary ideals (e.g., emphasis on natural rights, popular sovereignty, distrust of executive power).

• 1 mark for describing how this influence appeared in state constitutions (e.g., inclusion of written declarations of rights, stronger legislatures, limited executive authority).

• 1 mark for explaining why revolutionary ideals led to this development (e.g., fear of tyranny, commitment to protecting individual liberties).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which revolutionary ideals reshaped American society in the period following independence. In your answer, consider at least two social groups.

Question 2

• 1–2 marks for a clear explanation of how revolutionary ideals affected at least one social group (e.g., women, enslaved people, free Black communities, property-holding white men).

• 1–2 marks for a second, distinct example showing social change or continuity.

• 1 mark for evaluating the extent of change (e.g., noting both expanded opportunities and persistent inequalities).

• 1 mark for supporting the argument with accurate, relevant evidence from the period (e.g., emergence of republican motherhood, antislavery petitions, gradual emancipation laws, continued property restrictions on voting).