AP Syllabus focus:

‘British efforts to tighten control and colonial demands for self-government drove an independence movement, shaped by the Seven Years’ War and escalating disputes with Britain.’

The growing tension between Britain and its North American colonies transformed imperial relationships, encouraged new political expectations, and pushed diverse colonial groups toward an independence movement they had not originally sought.

The Shift Toward Imperial Control After 1754

Britain’s tightening control in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War marked a decisive shift in imperial governance. The war left Britain with vast new territorial claims in North America and an immense national debt, prompting policymakers to reassess colonial administration. Before 1763, Britain had largely practiced salutary neglect, allowing colonies to enjoy broad autonomy in legislating, taxing, and managing internal affairs. Postwar conditions convinced British leaders that this loose supervision needed replacement with structured oversight.

Postwar Policies and Their Rationale

British efforts to reform imperial governance grew from several overlapping goals:

Strengthening military defenses after defeating France.

Protecting new western boundaries, especially against American Indian resistance.

Ensuring colonial financial contributions to the empire’s upkeep.

Reasserting the authority of Parliament over its overseas possessions.

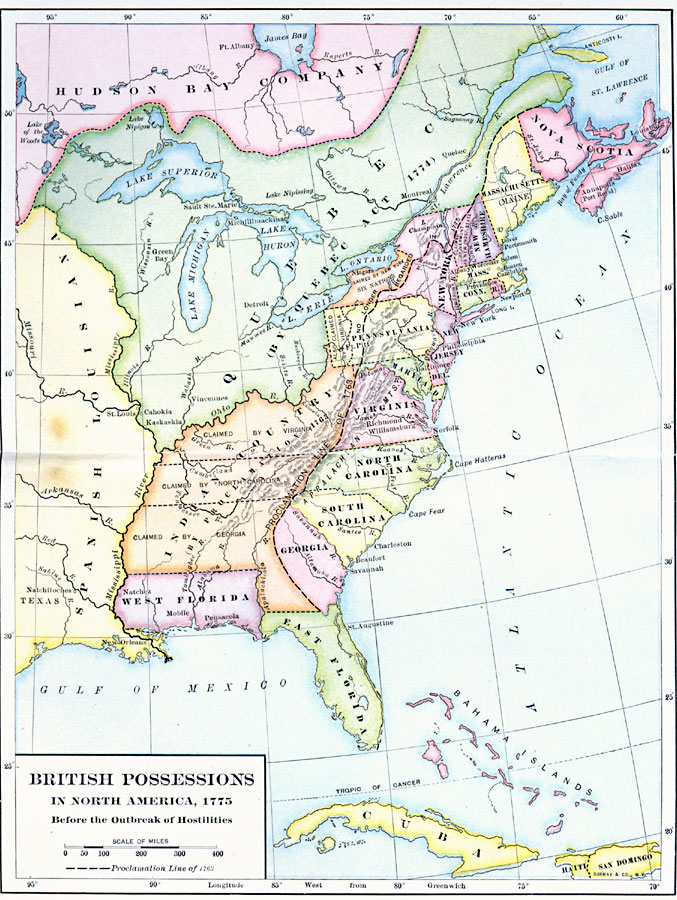

The Proclamation of 1763, designed to stabilize frontier tensions by restricting settlement beyond the Appalachians, symbolized this new direction. While intended as a pragmatic measure, settlers interpreted it as interference with their aspirations for westward expansion.

The Proclamation of 1763 barred settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains in an Indian Reserve, angering colonists who expected access to newly conquered lands.

Map showing British North America in 1775, including the Thirteen Colonies, Quebec, and the Proclamation Line of 1763. This visual highlights how postwar territorial arrangements and restricted settlement contributed to rising colonial resentment. Some geographic details exceed the AP syllabus focus but help illustrate the broader imperial context. Source.

Ideals of Self-Government and the Roots of Colonial Resistance

Colonists reacted strongly to these changes because they clashed with deeply held traditions of self-government, a concept defined as local political autonomy rooted in elected assemblies and limited royal interference.

Self-government: A political tradition in which colonists governed local affairs through elected assemblies, limiting direct imperial control.

These traditions evolved over generations of practical independence, causing colonists to view British reforms not as administrative necessities but as threats to established rights.

Legislative Conflict and Expanding Political Consciousness

Britain imposed new taxes and administrative structures, including the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Townshend Acts, all grounded in Parliament’s assertion of its right to legislate for the entire empire. Colonists countered with the principle of no taxation without representation, insisting that legitimate taxation required the consent of locally elected bodies.

Resistance sharpened colonial political identity:

Assemblies issued formal protests against Parliamentary overreach.

The Stamp Act Congress coordinated intercolonial responses, deepening political unity.

Nonimportation agreements demonstrated collective economic pressure as a tool of resistance.

These developments strengthened the idea that shared grievances could override regional differences.

Escalating Disputes and the Breakdown of Trust

By the late 1760s and early 1770s, disputes intensified, demonstrating how imperial reforms, when combined with colonial expectations, could rapidly erode trust. Efforts such as the Quartering Act and the creation of customs boards convinced many colonists that Britain planned to centralize authority at the expense of local liberties.

The Role of Violence, Perception, and Miscommunication

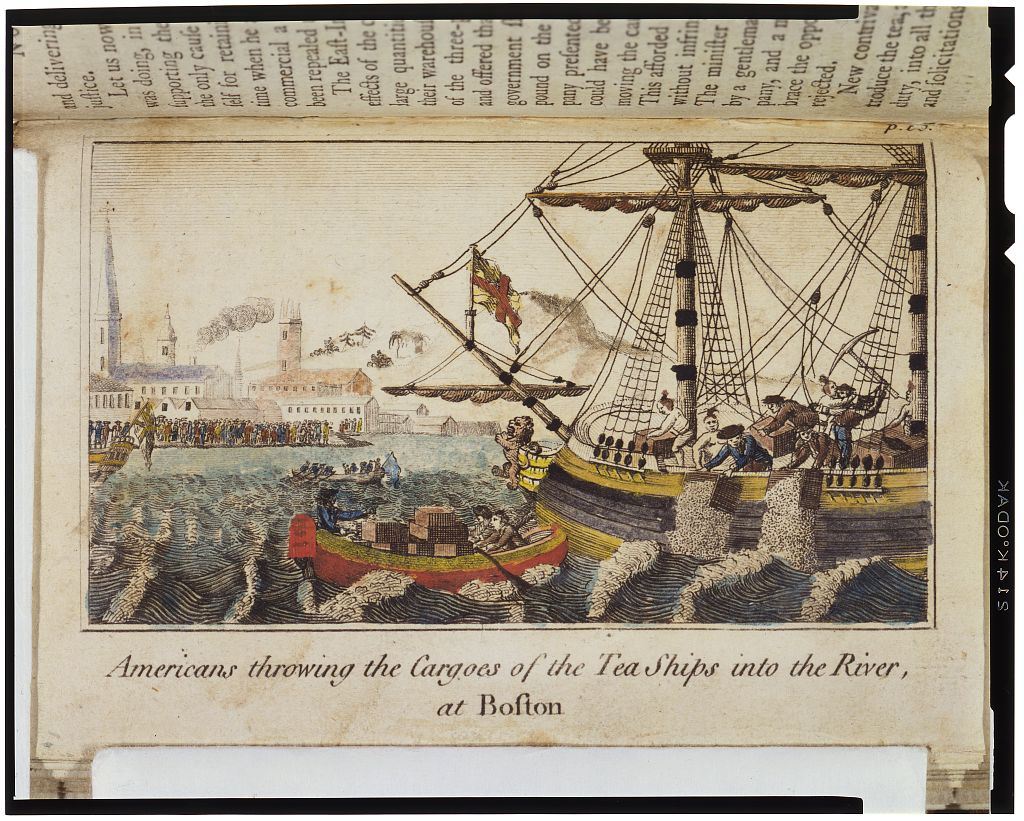

Incidents like the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773 amplified mutual suspicion. British leaders interpreted colonial defiance as rebellion, prompting punitive measures through the Coercive (Intolerable) Acts, which closed Boston Harbor and curtailed Massachusetts’ self-government. Colonists viewed these laws as proof that Britain intended to suppress political freedoms.

In Boston, conflict climaxed with the Boston Tea Party (1773), when colonists destroyed tea rather than submit to parliamentary taxation.

Engraving depicting colonists destroying tea aboard ships in Boston Harbor during the 1773 Tea Party. This dramatic act illustrates escalating colonial resistance to imperial taxation and parliamentary authority. Additional architectural and costume details extend beyond syllabus requirements but support deeper visual understanding of the event. Source.

Colonial communications networks—newspapers, committees of correspondence, and pamphlets—circulated accounts of conflict that framed British policy as inconsistent with the rights of freeborn English subjects. This rhetorical shift moved colonists from protest to a broader discussion of resistance and potential independence.

War as the Outcome of Increasingly Irreconcilable Visions

By the early 1770s, both sides had adopted incompatible visions of political authority. Britain insisted on the supremacy of Parliament, while colonists increasingly emphasized natural rights and local autonomy.

Steps Toward Armed Conflict

The independence movement emerged gradually, shaped by continued disputes:

The First Continental Congress (1774) organized collective responses and asserted a shared commitment to rights.

Colonists established local committees and militias to enforce boycotts and defend communities.

British attempts to seize colonial munitions in 1775 sparked armed resistance at Lexington and Concord, marking the transition from political conflict to open warfare.

Open warfare began at Lexington and Concord in 1775, when British troops attempting to seize colonial arms confronted local militias and fighting erupted.

As disputes escalated, colonists framed their cause around the protection of liberty and constitutional rights, while Britain viewed colonial actions as unlawful rebellion.

Independence as the End Result of Imperial Policies

The shift from imperial control to independence was not immediate or inevitable. Rather, it emerged from decades of growing tension, postwar anxieties, and hardened political positions. The Seven Years’ War transformed Britain’s imperial strategy, and in doing so, unintentionally set the colonies on a path toward severing their ties. Escalating disputes, fueled by ideological convictions and political missteps on both sides, ultimately propelled the colonies into a struggle for autonomy that developed into the American Revolution.

FAQ

British officials drew on long-standing ideas about parliamentary sovereignty, believing that Parliament held ultimate authority throughout the empire. This view meant that colonial assemblies were considered subordinate bodies whose autonomy was granted, not inherent.

Officials also assumed that imperial uniformity would strengthen the empire after the war. As a result, they believed tighter control was both legally justified and strategically necessary, even if colonists rejected that logic.

Colonists believed they possessed the same constitutional rights as people living in Britain, including consent to taxation and protection from arbitrary authority.

Post-war reforms appeared to undermine these rights because:

• taxes were imposed without representation

• enforcement mechanisms bypassed local assemblies

• limits on settlement contradicted expectations of land access

These changes convinced many colonists that their political status was being downgraded.

Economic frustration was central to the shift toward resistance. Colonists expected that victory over France would open new western lands and trade opportunities.

Instead:

• Britain restricted western migration

• new taxes targeted everyday commercial activity

• enforcement of customs regulations became more intrusive

The contrast between anticipated prosperity and imposed restrictions heightened resentment and encouraged arguments for greater autonomy.

British leaders underestimated how deeply colonial assemblies were embedded in local identity and governance. Many in Britain assumed that colonies functioned like other imperial possessions with limited political development.

Colonists, however, viewed their assemblies as legitimate expressions of civic participation. Policies that bypassed or constrained these bodies were therefore interpreted as deliberate attacks on constitutional rights rather than routine imperial management.

Many colonists sought reconciliation because they valued imperial trade networks, military protection, and shared cultural ties with Britain.

Reluctance stemmed from:

• fear that independence would lead to instability or war

• uncertainty about forming a unified colonial government

• hope that protests would convince Britain to restore earlier autonomy

Only after repeated clashes and punitive legislation did a broader movement for independence gain momentum.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which British attempts to tighten imperial control after the Seven Years’ War contributed to growing colonial resistance in British North America.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks for a clear and accurate explanation.

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant British action (e.g., new taxes, Proclamation of 1763, Quartering Act).

• 1 mark for describing how colonists reacted (e.g., protests, anger at limits on settlement, opposition to taxation without representation).

• 1 mark for linking the action directly to increased resistance (e.g., colonists felt their rights were being violated, leading to organised opposition).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how the Seven Years’ War and subsequent imperial policies contributed to the development of an independence movement in the American colonies between 1763 and 1775.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks for a well-developed explanation with supporting examples.

• 1–2 marks for describing consequences of the Seven Years’ War (e.g., large war debt, new territorial claims requiring administration and defence).

• 1–2 marks for explaining new imperial policies introduced after 1763 (e.g., taxation measures, enforcement of trade laws, restriction of westward settlement).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these policies contributed to an independence movement (e.g., colonial belief in self-government, coordinated resistance, breakdown of trust, escalation to armed conflict).