AP Syllabus focus:

‘Britain defeated France and expanded its territorial holdings, but the war’s tremendous cost encouraged new imperial efforts to raise revenue and consolidate colonial control.’

British victory in the Seven Years’ War transformed North America, dramatically expanding imperial territory while creating enormous war debt that reshaped colonial policy, relations, and resistance.

British Victory and the Reshaping of North America

The Defeat of France and Its Strategic Consequences

The Seven Years’ War, known in North America as the French and Indian War, concluded in 1763 with a decisive British triumph over France and its American Indian allies. This outcome ended more than a century of Franco-British rivalry on the North American continent. Through the Treaty of Paris (1763), Britain achieved dominance by eliminating France as a major territorial power in North America and severely weakening French influence among Indigenous nations.

Territorial Gains Under the Treaty of Paris

Britain’s newly acquired territory dramatically expanded the empire’s geographic scope:

Canada was ceded entirely to Britain, ending French colonial claims.

French lands east of the Mississippi River, except New Orleans, transferred to British control.

Spanish Florida was exchanged to Britain in return for Spain receiving Louisiana from France.

Britain gained strategic control over key port cities and interior regions essential to fur trade and military logistics.

This vast expansion created new administrative responsibilities and intensified the empire’s need for clearer oversight and revenue streams.

Map of North America in 1763 showing British, Spanish, and remaining French territories after the Seven Years’ War. The shaded regions highlight Britain’s new control over Canada and the land east of the Mississippi River. The map includes additional geographic details, such as early boundaries, which exceed the AP focus but help illustrate the wider scale of territorial change. Source.

The Tremendous Cost of War

Financial Burdens and Imperial Debt

The Seven Years’ War was among the most expensive conflicts Britain had ever fought. War expenditures included supporting colonial militias, mobilizing transatlantic fleets, financing European campaigns, and maintaining frontier forts. By 1763, Britain faced a crippling national debt, nearly doubling from its prewar level.

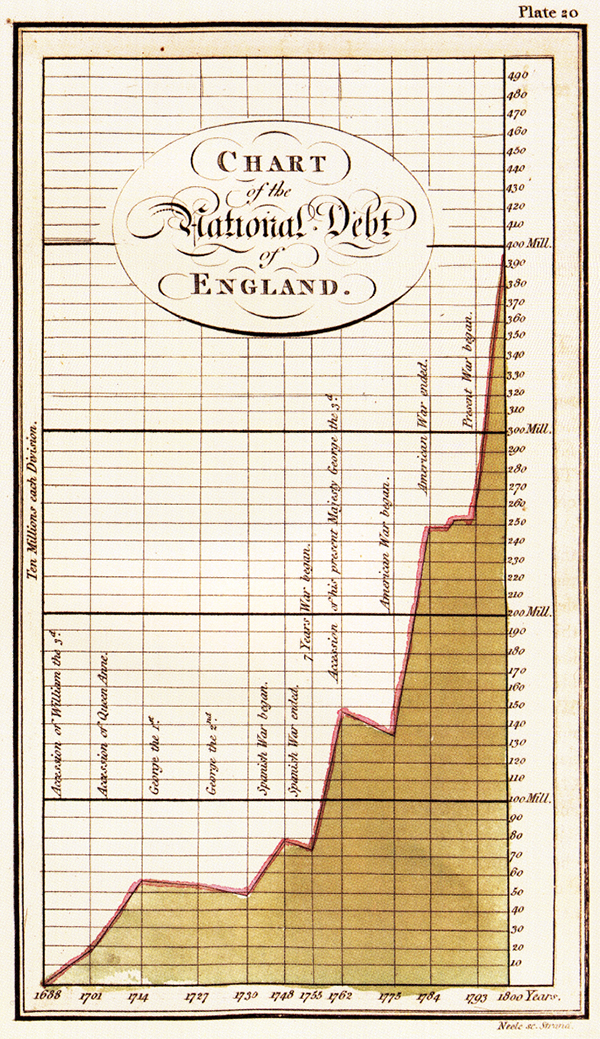

William Playfair’s “Chart of the National Debt of England” shows dramatic increases in British debt during major eighteenth-century conflicts, including the Seven Years’ War. The rising shaded area visually emphasizes how wartime spending strained Britain’s finances. The chart extends past 1763, adding broader context to the long-term fiscal pressures connected to imperial warfare. Source.

War Debt: The accumulated financial obligations incurred by Britain during the Seven Years’ War, requiring new revenue to pay interest and principal.

The financial strain convinced British leaders that the colonies, whose defense had required massive investment, should contribute substantially to imperial financial recovery. This reasoning became the foundation of Britain’s postwar fiscal and administrative reforms.

Maintaining an Expanded Empire

War’s end did not eliminate expenses. Britain now had:

New frontier posts to garrison

Longer borders to defend

Additional administrative systems to implement

Ongoing commitments to regulate trade and diplomacy with numerous Indigenous nations

The cost of maintaining these obligations pushed Britain toward policies that would fundamentally alter colonial–imperial relations.

Postwar Efforts to Raise Revenue

Consolidating Imperial Control

To stabilize finances and assert tighter authority, British policymakers introduced a series of measures meant to increase efficiency and reduce smuggling. These efforts aligned with the belief that colonies should serve the empire economically and politically.

Key initiatives included:

The Sugar Act (1764), adjusting duties and strengthening customs enforcement.

The Currency Act (1764), regulating colonial money to protect British merchants.

The Stamp Act (1765), imposing a direct internal tax on paper goods and legal documents.

These policies embodied the shift from salutary neglect—Britain’s earlier hands-off approach—to active supervision of colonial economies.

Shifts in Administrative Philosophy

British officials viewed postwar reforms as rational and necessary. They believed:

Colonists had benefited from British military protection.

Colonial trade had flourished under imperial defense.

Shared responsibility for empire was both logical and fair.

However, colonists perceived these measures as infringements on local autonomy and traditional self-governance practices.

Colonial Reactions to Postwar Reforms

Rising Tensions Rooted in War’s Aftermath

The same victory that secured British supremacy created the conditions for political strain. As Britain sought revenue to manage its enlarged empire, colonists increasingly feared that the new taxes represented an attempt to impose unrepresented authority over their affairs.

Colonial protests centered on several claims:

Only colonial legislatures could levy internal taxes.

British regulars stationed in peacetime posed threats to liberty.

Trade regulations restricted economic opportunity.

These reactions emerged directly from Britain’s attempts to remedy its staggering war debt.

The Link Between Territorial Gains and Imperial Strain

The expanded borders gained from France required sustained military presence, contributing to ongoing expenses that justified new revenue measures. As a result:

Britain tightened customs enforcement along the Atlantic coast.

Soldiers were stationed in western forts to prevent renewed conflict.

Colonists bore the brunt of policies intended to stabilize imperial finances.

Colonial discontent grew because expansion increased not only British authority but also colonists’ belief that they deserved greater voice in imperial governance, especially after their wartime contributions.

The War as the Economic and Political Turning Point

From Shared Victory to Growing Division

Although Britain emerged from the Seven Years’ War with unmatched territorial dominance, the conflict created a financial and administrative burden that transformed imperial policy. Measures intended to raise revenue and consolidate control, as highlighted in the AP syllabus, became the catalyst for colonial resistance. Within a decade, disputes over taxation, representation, and constitutional rights would escalate into the American Revolution—rooted fundamentally in the financial consequences of British victory.

FAQ

Many Britons believed the colonies should help pay for imperial defence, especially since the war had begun in North America and had protected colonial frontiers.

Public opinion generally supported new taxation measures as a fair redistribution of the burden.

However, critics worried that increased taxation at home was already too heavy, reinforcing the idea that the colonies should contribute more substantially to imperial finances.

The newly acquired regions were vast, sparsely populated by Europeans, and home to numerous Indigenous nations with distinct diplomatic expectations.

Administration required an expanded military presence, new civil structures, and careful management of trade relationships.

These complexities strained Britain’s capacity and encouraged officials to centralise control over colonial affairs to reduce costs and improve oversight.

Indigenous nations expected continued negotiation through gift-giving and diplomatic councils, practices considered essential for maintaining peace.

These interactions were costly and required ongoing military and diplomatic personnel in frontier regions.

Failure to maintain these practices risked conflict, which could further increase Britain’s financial burden.

Britain sought to regulate westward colonial settlement and maintain stability by keeping troops stationed along the frontier.

These troops required supplies, transport, and long-term funding.

The need to sustain this military presence increased imperial expenses and fuelled British determination to raise revenue from the colonies.

Colonial economies grew significantly during the mid-18th century, especially through trade in commodities such as timber, fish, and tobacco.

Colonists also paid comparatively low direct taxes compared with Britons, leading imperial officials to view them as under-taxed.

Because the war had secured colonial territories and trade routes, British policymakers argued that the colonies’ prosperity justified higher financial contributions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War led to changes in its relationship with the American colonies.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a basic change (e.g., Britain imposed new taxes).

2 marks: Explains how the war’s cost or territorial gains contributed to this change.

3 marks: Provides clear, accurate explanation linking British debt or expanded empire to specific policy shifts (e.g., the Sugar Act, Stamp Act) and colonial reactions.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how Britain’s territorial gains and war debt after the Seven Years’ War contributed to growing colonial resistance in the period 1763–1770.

Question 2

4 marks: Describes British territorial gains and mentions war debt with some link to colonial resistance.

5 marks: Offers a developed explanation of how expanded territory and financial pressures led to revenue-raising policies and heightened tensions.

6 marks: Provides a well-structured analysis connecting territorial expansion, imperial fiscal reforms, and colonial ideological opposition, demonstrating clear understanding of cause-and-effect relationships.