AP Syllabus focus:

‘After the British victory, limits on westward settlement provoked colonial opposition, while Native groups sought to keep trading with Europeans and resist encroachment on tribal lands.’

The Proclamation Line of 1763 limited western settlement, angered many colonists, and prompted Native nations to defend land, secure trade, and navigate shifting imperial power.

Proclamation of 1763: Royal decree issued by King George III establishing a boundary along the Appalachians that restricted colonial settlement westward and reserved lands for Native peoples.

The Proclamation Line in the Postwar World

At the end of the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War), Britain gained vast new territories in North America. Managing this expanded empire was costly and complicated, especially along the frontier. In response to continuing Native resistance, particularly Pontiac’s Rebellion, British officials issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, drawing the Proclamation Line roughly along the Appalachian Mountains and limiting colonial expansion beyond it.

Map showing the Proclamation Line of 1763 along the Appalachians and the designated Indian Reserve to the west. The map also presents the later Indian Boundary Line of 1768, which extends beyond the syllabus but illustrates shifts in frontier boundaries. Key geographic features and boundary lines are clearly marked for easy interpretation. Source.

The proclamation reserved land west of the Appalachian crest as “Indian territory”, intended to serve as a large Native reserve where Indigenous nations could continue to live and trade without constant settler intrusion.

British Goals: Order, Economy, and Frontier Peace

Strategic Aims of the Proclamation

British policymakers had several overlapping goals when they imposed limits on westward settlement:

Reduce frontier violence by separating colonists from Native communities and avoiding another large, expensive war like Pontiac’s Rebellion.

Centralize control over land sales, allowing only the Crown—not colonial assemblies or private speculators—to purchase Native lands and issue grants.

Cut imperial costs by preventing scattered settlements that would require costly military protection.

Regulate trade with Native nations through licensed traders and official posts, tightening imperial oversight over frontier commerce.

By asserting that only the king’s government could negotiate land cessions, Britain tried to strengthen imperial authority over both colonists and Native peoples.

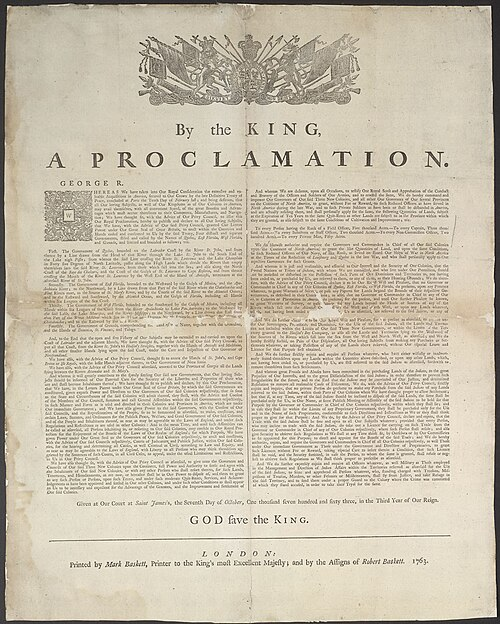

Broadside printing of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, formally outlining imperial rules for western expansion and relations with Native nations. The prominent heading emphasizes the top-down nature of imperial governance. The document’s full legal detail goes beyond the syllabus but helps illustrate the proclamation’s official and authoritative tone. Source.

Colonial Opposition: Expectations vs. Imperial Limits

Why Colonists Resented the Proclamation

Many colonists saw the Proclamation Line as a violation of what they believed were their rights and expectations after fighting alongside Britain. Their anger had several roots:

Land speculation and investment

Wealthy colonists and British investors had purchased or been promised western lands, expecting profits once settlement expanded.

The proclamation canceled or blocked many land grants, directly harming speculators’ interests.

Veterans’ rewards

Colonial soldiers anticipated land grants in the newly conquered territories as payment for wartime service.

The restriction on new settlements undercut these promised rewards.

Charter claims and colonial autonomy

Several colonies—such as Virginia—claimed territory “from sea to sea” in their charters.

The imperial boundary seemed to override colonial charters and undermine colonial self-government in land policy.

Perceived infringement on British rights

Many colonists believed that, as British subjects, they had a right to move into available imperial lands.

Limits on westward migration felt like an arbitrary restriction imposed by a distant government.

Forms of Colonial Defiance

Despite the law, colonial resistance was often practical rather than openly revolutionary at this stage:

Squatting and illegal settlement west of the line, especially in the Ohio Valley and Kentucky region.

Unofficial land deals between colonists and Native groups, bypassing the Crown’s rules.

Political protests and petitions from colonial assemblies and land companies, demanding relaxation or revision of the boundary.

This mixture of everyday defiance and political complaint helped build a pattern of colonial opposition to imperial control that would intensify in later disputes over taxation and representation.

Native Resistance and Indigenous Strategies

Protecting Land and Autonomy

For Native nations, the Proclamation of 1763 was both a response to their resistance and a tool they tried to use for their own purposes. The British hoped the line would conciliate Native Americans by checking settler encroachment, recognizing that continued land loss had helped provoke Pontiac’s Rebellion.

Native groups pursued several strategies in this new environment:

Leveraging the boundary

Indigenous leaders cited the Proclamation to justify their claims that lands west of the line were theirs.

They insisted British officials enforce the boundary against illegal settlers.

Maintaining and expanding trade

Native groups aimed to keep trading with Europeans, using British and remaining French traders to obtain manufactured goods, weapons, and supplies.

Control over trade routes and access to posts remained central to Indigenous power.

Continuing resistance and negotiation

Some Native communities destroyed unauthorized settlements and resisted colonists who crossed the line.

Others used diplomacy and treaty-making to secure recognition of territorial boundaries and regulate trade under the new imperial regime.

Map of Native American territorial delimitations between 1763 and 1770, including the Proclamation Line of 1763 and later treaty boundaries. Some later lines exceed the syllabus scope but help illustrate how Native diplomacy and resistance reshaped frontier boundaries. The map visually highlights overlapping claims across the trans-Appalachian region. Source.

Limits of Protection

Although the Proclamation was written to preserve Native territories on paper, its effectiveness depended on British willingness and ability to enforce it. In practice:

The frontier was too vast for consistent enforcement.

British officials often prioritized colonial and imperial economic interests over strict protection of Native lands.

Native groups continually had to reassert their claims, facing renewed waves of settlement despite the official boundary.

A Growing Rift in the Empire

The Proclamation Line, colonial opposition, and Native resistance together marked a major turning point in imperial relations after the Seven Years’ War. Britain’s attempt to regulate land and trade through a top-down boundary confirmed for many colonists that imperial policy could conflict with their local interests and expectations. At the same time, Native nations seized on the proclamation as one tool—among many strategies of diplomacy and resistance—to limit encroachment and safeguard their trade networks and homelands in a rapidly changing North American world.

FAQ

Gift-giving had long been central to alliances between European powers and Native nations, symbolising goodwill, reciprocity, and mutual obligations.

After 1763, British officials resumed gift-giving practices that had been curtailed before Pontiac’s Rebellion. This helped repair relationships damaged by earlier British attempts to cut costs by limiting diplomatic expenditure.

Although these gifts eased tensions, Native leaders viewed them as part of ongoing negotiation rather than a substitute for respecting territorial boundaries.

Many settlers had moved into the Ohio Valley and other western regions before 1763, often without formal land titles.

After the Proclamation:

These settlers were classified as living illegally on Native land.

British officials sometimes attempted to remove them, though enforcement was inconsistent.

Some settlers resettled east of the line, while others stayed and relied on sympathetic colonial politicians to defend their claims.

Their presence further undermined the Proclamation’s aim of stabilising frontier relations.

Land speculation companies, such as the Ohio Company and the Loyal Land Company, had already invested heavily in vast tracts of territory west of the Appalachians before the Proclamation Line was announced.

Their financial interests meant that the prohibition on settlement directly threatened expected profits. Company leaders lobbied colonial assemblies and British officials for exemptions, helping turn opposition into organised political pressure.

Their influence ensured that criticism of the Proclamation was not just popular but also driven by wealthy, well-connected elites with clear economic motivations.

Frontier garrisons were understaffed and spread thin across vast territories.

British officers faced several obstacles:

Weak logistical support from London.

Ongoing conflicts with settlers determined to move westward despite the law.

The need to negotiate with multiple Native nations while also policing colonial behaviour.

These limitations meant the Proclamation was often ignored in practice, reducing British credibility among both colonists and Native groups.

Although the Proclamation Line appeared to protect Native land, many Indigenous groups doubted Britain’s willingness to enforce it rigorously.

Their scepticism stemmed from:

Long experience of colonial governments ignoring previous land agreements.

Continuous settler pressure that often went unpunished.

Britain’s competing priorities, which frequently favoured colonial economic interests.

As a result, Native groups treated the Proclamation as a temporary safeguard rather than a lasting guarantee, continuing to pursue alliances and resistance strategies independently.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the Proclamation Line of 1763 provoked opposition among British colonists.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., restricted access to western lands).

1 mark for providing additional detail or context (e.g., colonists had already invested in or settled these lands).

1 mark for explaining why this created opposition (e.g., colonists believed the restriction violated their rights as British subjects or contradicted wartime expectations).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how Native groups responded to British attempts to limit westward settlement after 1763.

Mark Scheme:

1–2 marks for identifying specific Native responses (e.g., diplomatic negotiations, resistance to illegal settlement, maintaining trade networks).

1–2 marks for explaining how these actions helped Native groups defend land, autonomy, or economic interests.

1–2 marks for demonstrating broader understanding (e.g., linking responses to the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War, Pontiac’s Rebellion, or shifting imperial relationships).