AP Syllabus focus:

‘Compromises such as the Missouri Compromise only temporarily eased tensions between defenders and opponents of slavery as sectional conflict grew.’

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 revealed deepening national divisions over slavery, illustrating the limits of political compromise as expanding territories intensified sectional tensions in the United States.

The Road to the Missouri Compromise

Growing sectional conflict shaped early national politics as leaders struggled to balance the interests of free and slave states. The debate emerged when Missouri applied for statehood in 1819 with slavery already established, raising concerns about the future balance of power in the Senate. Many Northerners feared that admitting Missouri as a slave state would extend the influence of the slaveholding South, while Southern leaders insisted that restricting slavery’s expansion threatened their constitutional rights and economic security.

Early Proposals and Rising Sectional Tensions

Northern congressman James Tallmadge Jr. introduced an amendment to prohibit the further introduction of enslaved people into Missouri and require gradual emancipation.

Gradual emancipation: A plan to phase out slavery over time by freeing future generations or setting age-based release conditions.

Southern legislators rejected the proposal, interpreting it as an attack on slavery itself. The debate quickly became a national crisis because it signaled the difficulty of containing sectional disagreements within the existing political framework. As both sides hardened their positions, talk of disunion appeared with alarming frequency.

The Compromise’s Core Provisions

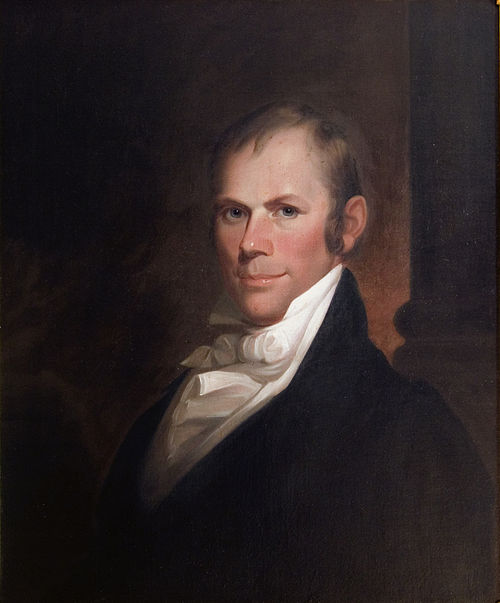

To resolve this impasse, congressional leaders crafted the Missouri Compromise, chiefly engineered by Henry Clay, an influential advocate of national unity.

This 1818 portrait shows Henry Clay, the Kentucky statesman who negotiated the Missouri Compromise. Clay sought to maintain sectional balance and national unity through legislative compromise. The image reinforces his key role as the “Great Compromiser.” Source.

The agreement contained three major components:

Missouri would enter the Union as a slave state.

Maine, previously part of Massachusetts, would enter as a free state, preserving the numerical balance in the Senate.

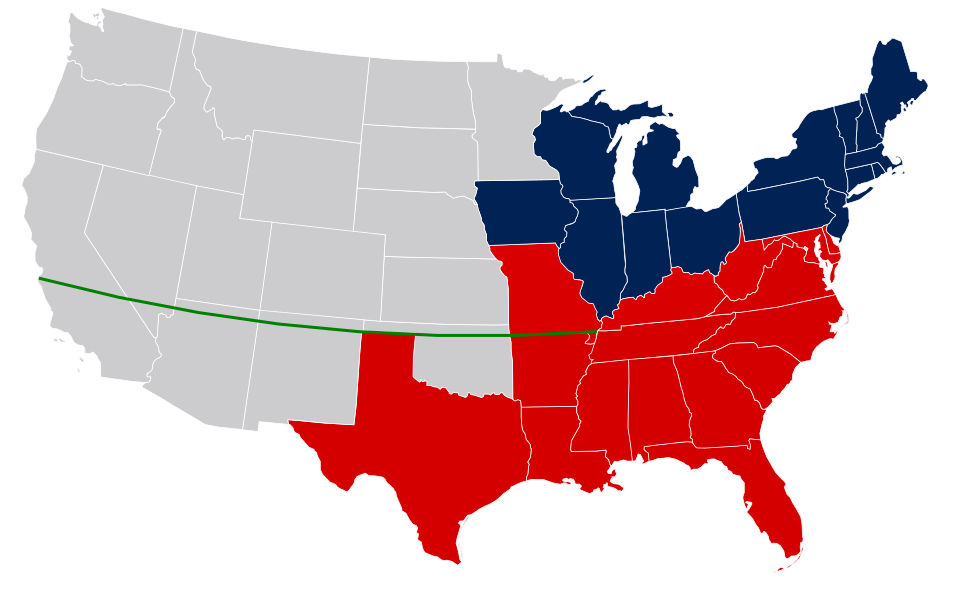

Slavery would be prohibited in the remainder of the Louisiana Territory north of the 36°30′ latitude line, except within Missouri.

This map highlights the Missouri Compromise line at 36°30′, clearly dividing free and slave regions in the Louisiana Territory. The color-coding reveals how geography shaped sectional politics. The map includes some later territorial boundaries not required by the syllabus. Source.

This arrangement temporarily calmed political tensions by providing a structural method for addressing future slavery debates. Yet it also institutionalized the notion that the nation could be divided geographically into free and slave regions, revealing the fragility of political solutions in the face of moral and economic conflict.

Sectional Reactions and Consequences

Although designed to preserve national unity, the Missouri Compromise intensified the awareness of distinct regional identities. Northerners largely accepted the line as a practical limit on slavery’s growth, while many Southerners viewed it uneasily, fearing that federal restrictions on slavery’s expansion set a dangerous precedent. The debate exposed underlying disagreements about constitutional interpretation and the federal government’s authority over territories.

Constitutional Questions

The controversy raised fundamental questions about congressional authority.

Popular sovereignty: The principle that political power resides with the people, who decide key issues such as slavery through voting.

Some Southerners argued that Congress had no right to restrict slavery in the territories, asserting that enslaved people were a form of property protected by the Constitution. In contrast, many Northerners believed Congress possessed broad power to regulate territories and prevent the spread of slavery for moral and political reasons. This disagreement pointed to the limits of using legislative compromise to solve a moral crisis.

The Limits of Political Compromise

Although the Missouri Compromise reduced immediate conflict, it did not address the underlying issues that made slavery such a divisive institution. Instead, it delayed a reckoning by offering a temporary political solution to a moral and economic divide. As the United States continued to expand westward, each new territory created renewed uncertainty about whether slavery would spread further.

Short-Term Peace, Long-Term Instability

Several factors show why the compromise ultimately could not prevent future conflict:

Geographic boundaries did not resolve ideological disputes over slavery.

Population growth in the North shifted the national political balance, increasing Southern fears of marginalization.

Expanding cotton production and the profitability of slavery created Southern insistence on protecting the institution.

Emerging abolitionist sentiment in the North challenged national unity and placed moral pressure on federal policy.

These conditions made it clear that compromise alone could not settle the sectional tensions that were quickly becoming central to American political life.

Prelude to Future Crises

Later disputes such as the Mexican Cession, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act demonstrated that the Missouri Compromise served only as a temporary barrier to growing sectionalism. Once the 36°30′ line was challenged or ignored, the political system again faced the inescapable question of slavery’s expansion. The Missouri Compromise thus became an early indicator that the United States lacked a durable solution to managing the competing interests of free and slave states.

The Missouri Compromise in AP U.S. History Context

This subsubtopic emphasizes that compromises like the Missouri Compromise offered short-lived stability but failed to resolve fundamental disagreements. The growing inability to find lasting political solutions underscores how the sectional conflict deepened and ultimately paved the way toward the Civil War.

This classroom map titled “The Missouri Compromise 1820” visually divides the nation into free and slave regions. Its shaded blocks help students understand how the compromise attempted to impose geographic order on sectional tensions. The decorative border and additional geographic details exceed syllabus requirements but can be ignored. Source.

FAQ

Many Northern politicians feared that admitting Missouri as a slave state would strengthen the South’s influence in the Senate and national policymaking.

They also worried that expanding slavery into new western territories would entrench Southern political dominance for decades, making it harder to challenge slavery’s national role.

Some Northerners additionally believed that slavery’s geographic expansion would slow free labour migration and undermine opportunities for independent farmers.

The compromise exposed fractures within both North and South.

• Moderates generally supported compromise to maintain the Union and avoid conflict.

• Radicals in the South argued that any limit on slavery’s expansion threatened their rights.

• Radicals in the North believed compromise allowed slavery to continue spreading and normalised its presence in national politics.

This growing ideological distance made future agreements harder to negotiate.

The crisis encouraged Americans to view political issues increasingly through a sectional lens.

For many Southerners, defending slavery in the territories became central to regional identity and perceived security.

For many Northerners, restricting slavery’s expansion became associated with economic opportunity, free labour values, and moral principle.

These developing identities persisted and solidified throughout the 1820s, shaping political alignments long after the compromise.

Southerners believed the amendment signalled a new willingness in Congress to interfere with slavery where it already existed.

They feared that restricting the movement of enslaved people into Missouri would undermine the economic foundations of slaveholding by reducing the ability to expand plantation agriculture.

More broadly, Southern leaders interpreted it as a precedent for federal authority over slavery, which they argued should be protected from national interference.

The compromise raised enduring questions about Congress’s authority to regulate slavery in the territories.

• Some later debates, including those over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, built directly on arguments first aired in 1820.

• Supporters of federal limits on slavery cited the compromise as precedent for congressional control.

• Opponents used it to argue that restrictions on slavery’s expansion were temporary political bargains, not constitutional principles.

These unresolved issues shaped national political discourse for decades.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain why the Missouri Compromise of 1820 failed to provide a permanent solution to sectional tensions in the United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a basic reason for the compromise’s failure, such as the continued disagreement over the expansion of slavery.

2 marks: Provides a valid explanation of why the compromise only temporarily eased tensions, for example noting that it avoided but did not resolve the underlying moral and economic conflict over slavery.

3 marks: Offers a clear, developed explanation that includes specific detail (e.g., geographic division at 36°30′, future territorial expansion reigniting conflict, or Southern fears of federal limitations on slavery).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1800–1848, analyse how the Missouri Compromise illustrated both the possibilities and the limits of political compromise in addressing disputes over slavery.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Provides a general explanation of how the Missouri Compromise attempted to maintain balance and reduce tensions, with some discussion of its limitations.

5 marks: Gives a more detailed analysis, referencing elements such as the admission of Missouri and Maine, the 36°30′ line, or the sectional interests motivating each side. Shows some awareness of broader historical context, such as westward expansion or early sectionalism.

6 marks: Presents a well-argued and accurate analysis that integrates specific evidence, links the compromise to wider political and constitutional debates, and clearly explains why the compromise both temporarily stabilised politics and highlighted the deeper divisions that made long-term resolution unlikely.