AP Syllabus focus:

‘More Americans, including factory workers, moved away from semi-subsistence agriculture and supported themselves by producing goods for distant markets.’

Transformation of Work in a Growing Market Economy

Between 1800 and 1848, expanding transportation networks, rising commercial opportunities, and the spread of industrial technologies reshaped how Americans earned their livelihoods. The shift away from semi-subsistence agriculture meant that individuals and families produced not merely for their own needs but for sale in broader markets. This change altered daily labour routines, regional production strategies, and the economic place of households within the national economy.

Decline of Semi-Subsistence Agriculture

Before the Market Revolution, most American families relied on producing food, clothing, and household goods for their own use. As market access improved, many households redirected their labour toward surplus production intended for sale.

Key developments included:

Increased planting of marketable crops such as wheat, corn, and livestock.

Greater reliance on purchased goods—such as cloth, tools, and manufactured items—rather than home-produced alternatives.

Participation in local and regional trade networks that linked farms to towns and cities.

Semi-Subsistence Agriculture: A form of farming in which families grow or make most goods for their own consumption, engaging minimally in outside markets.

This shift encouraged specialisation and reduced the economic isolation that had characterised much rural life before the early nineteenth century.

Growth of Wage Labour and Industrial Employment

As factories multiplied, more Americans earned wages in manufacturing rather than relying solely on farm-based production. In textile mills, ironworks, and workshops, workers sold their labour for cash that enabled them to buy goods previously made within the home.

Characteristics of early industrial employment included:

Long hours structured by factory time discipline.

Operation of machinery that reduced workers’ autonomy.

Expansion of a labour force that included women, children, and rural migrants.

Household Production in Transition

Even as wage labour expanded, households remained essential units of economic activity. Families adapted to changing conditions by modifying traditional household roles and incorporating new forms of production that complemented market participation.

Emergence of a Mixed Household Economy

Many families operated a mixed economy, growing food for their own consumption while selling surplus crops, animal products, or handcrafted goods in nearby markets.

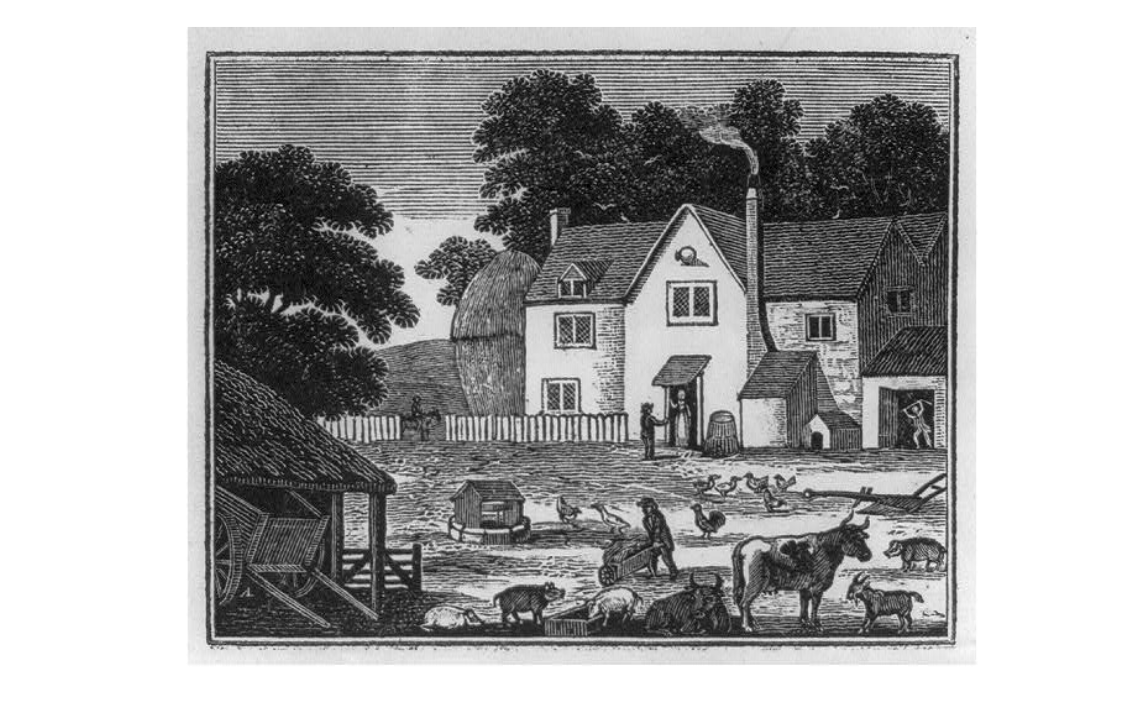

This early 19th-century woodcut depicts a rural household in which family members, animals, and buildings operate together as a unified working landscape. It illustrates how mixed household economies combined subsistence activities with surplus production for sale. Some visual elements exceed AP requirements, but the scene accurately conveys how work, land, and family life intertwined during the Market Revolution. Source.

Such mixed economies typically featured:

Women continuing some forms of domestic manufacture, such as butter, textiles, or clothing.

Men dividing labour between wage opportunities and farm responsibilities.

Children contributing labour both within the home and in paid employment.

Household Economy: An economic system in which families combine domestic labour, farm work, and market-oriented activities to sustain and improve their livelihoods.

The persistence of household production reflected both cultural expectations and practical necessity during economic transition.

Women’s Roles in Household and Market Production

Women’s labour remained central to household survival and adaptation. While many women continued domestic tasks, others entered the paid workforce or engaged in home-based production for sale.

Women contributed in several key ways:

Producing textiles, dairy products, or prepared foods for local markets.

Undertaking piecework, sewing garments or goods for manufacturers who supplied raw materials.

Managing household purchases as families relied more heavily on market goods.

Within the household, women and children often performed domestic production such as spinning, sewing, preserving food, and making candles.

This painting shows a rural interior where domestic work formed an essential part of family subsistence and market participation. The modest furnishings and multitasking space illustrate how production occurred within the home. Although painted after 1848, it reflects labour patterns rooted in the early Market Revolution. Source.

These responsibilities strengthened women’s economic influence within the home, even as gender norms emphasised domesticity.

Rise of Commercial Production and Regional Specialisation

The gradual decline of self-sufficiency encouraged regions to focus on producing goods best suited to their environments and transport links.

Integration of Rural Households into National Markets

Improved roads, canals, and river systems enabled rural producers to sell their goods to distant buyers. The Midwest supplied grain and livestock to urban centres, while the Northeast specialised increasingly in manufactured goods.

This integration fostered:

A growth in commercial farming, using tools and techniques aimed at maximising surplus.

Increased dependence on credit, merchants, and transportation systems.

Greater vulnerability to fluctuations in national and international markets.

Rural families now made economic decisions based on prices and demand far beyond their immediate communities.

Artisans and the Changing Nature of Skilled Work

Craft workers experienced significant changes as mechanisation and factory production undercut traditional artisanal independence.

Important transformations included:

Declining control over pace, method, and quantity of production.

Loss of local markets to cheaper factory-made goods.

Movement of artisans into wage labour or supervisory positions within factories.

These shifts signalled the erosion of older forms of economic autonomy.

Cultural and Social Implications of Market-Oriented Production

The reorganisation of work altered Americans’ sense of independence, family dynamics, and community structures.

Changing Ideas of Independence and Economic Identity

As more families participated in the market, economic independence became defined not by self-sufficiency but by the ability to earn wages or generate surplus goods for sale.

Textile mills, especially in New England towns like Lowell, Massachusetts, drew young women into wage work as “mill girls,” living in company boardinghouses and working long hours on power looms.

This stereoscopic photograph displays the crowded, machinery-filled interior of a cotton mill, highlighting the industrial workspaces that replaced many forms of household production. Rows of looms and powered equipment reveal the regimented environment in which factory operatives worked. Though slightly later than the AP period, the image closely reflects conditions encountered by earlier mill workers. Source.

This change:

Broadened the meaning of productive labour beyond the farm or household.

Encouraged ambition, mobility, and engagement with commercial opportunities.

Increased pressure on families to adapt to shifting market demands.

Work and household production in the Market Revolution thus reshaped economic life, drawing Americans into interlinked networks of labour, consumption, and exchange.

FAQ

With more factory-made goods available, households no longer needed to produce certain items themselves. Tasks such as spinning thread, weaving cloth, or crafting tools declined in importance.

This allowed families to reallocate time toward activities that could generate marketable surpluses, such as dairy production, specialised crop cultivation, or piecework.

Market opportunities fluctuated, making complete dependence on wage labour or commercial farming risky. Mixed household economies created a buffer against downturns.

Families could combine:

Subsistence gardening

Limited livestock raising

Seasonal wage work

Small-scale sale of handmade goods

This diversification helped maintain stability during periods of price instability or crop failure.

Children continued to perform essential household tasks, but many also entered wage labour in mills, workshops, or agricultural seasonal work.

This dual role meant they often balanced:

Domestic chores

Schooling (where available)

Paid or semi-paid tasks that supplemented family income

Their labour became increasingly tied to market needs rather than purely household survival.

Families living near canals, turnpikes, or navigable rivers found it easier to transport surplus goods to market. This encouraged them to specialise in products that could be profitably sold elsewhere.

Improved transport also lowered the cost of purchasing goods, making market reliance more attractive and reducing the economic incentive for producing everything at home.

Geography, family needs, and local economic conditions shaped women’s choices. Urban and mill-town settings provided more wage opportunities, while rural areas relied more heavily on domestic production.

Additionally:

Family financial pressure encouraged wage work

Cultural expectations emphasised home-based labour

Availability of piecework allowed women to blend household and market roles

These factors created diverse patterns of women’s economic contribution during the Market Revolution.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Market Revolution changed household production in the United States between 1800 and 1848.

Mark Scheme (Question 1)

1 mark for identifying a valid change (e.g., increased reliance on purchased manufactured goods).

1 mark for explaining how this change altered household production (e.g., families produced fewer goods for themselves and redirected labour toward marketable outputs).

1 mark for a specific supporting detail (e.g., decline of home spinning and weaving due to availability of factory-made textiles).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the shift from semi-subsistence agriculture to market-oriented production transformed family labour patterns in the period 1800–1848.

Mark Scheme (Question 2)

1 mark for a clear thesis assessing the extent of transformation.

1–2 marks for describing changes in men’s labour (e.g., increasing participation in wage work or commercial farming).

1–2 marks for describing changes in women’s and children’s labour (e.g., rise of piecework, domestic production for sale, or children’s mixed home and wage labour).

1 mark for recognising continuity or limits (e.g., households still relied on domestic production for economic stability).

Answers must use accurate evidence from the Market Revolution era.