AP Syllabus focus:

‘Large numbers of immigrants moved to industrializing northern cities, while many Americans migrated west of the Appalachians to build communities along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.’

Migration and Population Mobility in the Early Republic

Migration between 1800 and 1848 accelerated dramatically due to economic opportunities, transportation improvements, and demographic pressures. These combined forces expanded the nation’s population centers and fueled the formation of new communities in both urban and rural settings.

Domestic Migration West of the Appalachians

Large numbers of Americans relocated beyond the Appalachian Mountains, attracted by abundant land and the promise of economic mobility.

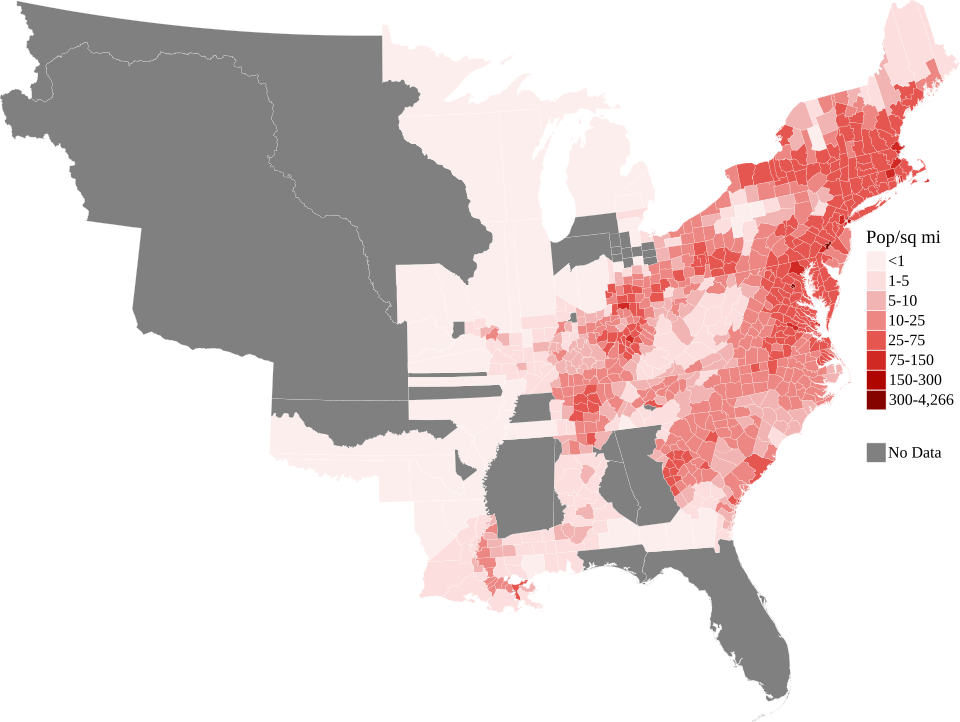

This 1820 population density map shows how most Americans remained concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard while interior regions such as Ohio and Kentucky began to fill with new settlers. Darker shading highlights more densely populated counties, illustrating early stages of westward expansion. Students are not expected to memorize county details, but should recognize the broader pattern of growing interior settlement, which slightly exceeds the syllabus’s basic expectations. Source.

Many migrants traveled via routes such as the National Road, the Cumberland Gap, and expanding river networks.

Frontier families often relied on subsistence farming initially, gradually shifting toward participation in the market economy as transportation links improved.

New states—such as Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Mississippi, and Alabama—experienced rapid population growth due to this movement.

Frontier: A sparsely settled area at the edge of existing settlement where new communities formed through migration and land cultivation.

As migrants established farms and towns, they contributed to the region’s economic diversification. Commercial agriculture expanded, and new institutions such as county courthouses, churches, and local markets structured social and civic life.

Development of Western Communities

Western settlements grew around rivers such as the Ohio and Mississippi, which facilitated transportation, trade, and access to distant markets.

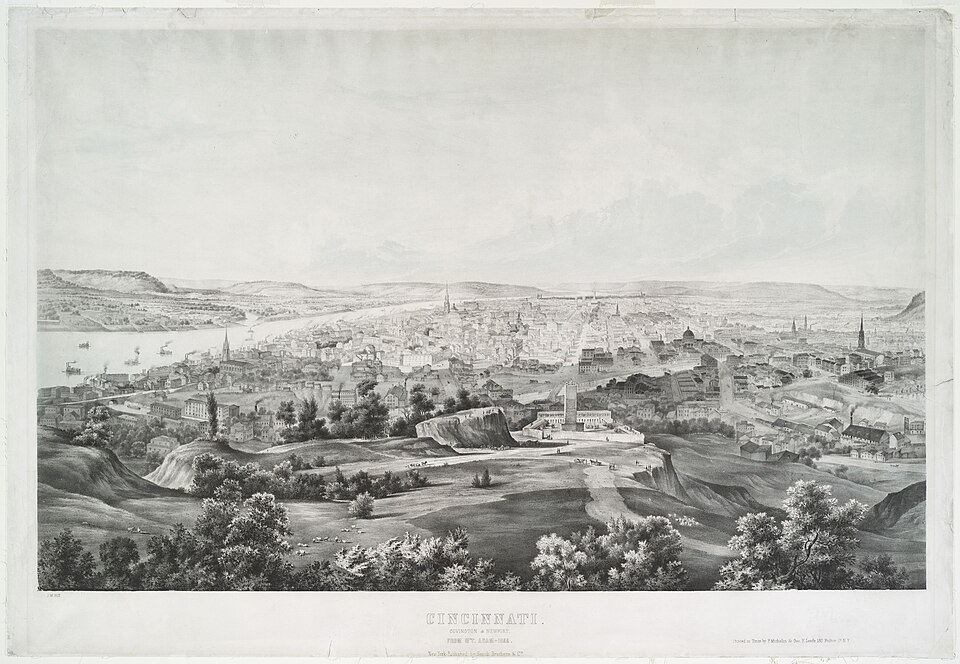

This 1852 engraving shows Cincinnati and nearby river towns developing as commercial hubs along the Ohio River, with wharves, warehouses, and growing urban neighborhoods. The image reflects how western river cities became key centers linking agricultural communities to distant markets. Though slightly later than the 1800–1848 period, it accurately illustrates urban forms emerging from earlier migration trends. Source.

Towns like Cincinnati and St. Louis became central marketplaces linking farmers with national commerce.

Community-building involved the construction of schools, mills, and local governance structures, providing stability in rapidly growing regions.

Cultural blending occurred as migrants from different states mixed, creating distinctive regional identities shaped by shared frontier experiences.

Subsistence Farming: A mode of agriculture in which families produce primarily for their own consumption rather than for market sale.

Although western communities benefited from opportunity, their growth also increased pressures on Indigenous lands and intensified conflicts over territorial control and sovereignty.

Urbanization in the Industrializing North

Urban growth intensified as northern cities became magnets for both immigrants and rural Americans seeking new employment opportunities created by early industrialization.

Immigration and Urban Population Growth

The early nineteenth century witnessed rising immigration from Europe, particularly from Ireland and Germany, though immigration would increase even more dramatically after 1845. Industrializing cities offered wage labor, manufacturing jobs, and expanding commercial industries.

Immigrants often settled in port cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore before spreading to inland industrial centers.

Growing ethnic neighborhoods helped maintain cultural continuity while also contributing to the diversity of urban life.

New forms of voluntary associations, churches, and aid societies supported immigrant populations as they adapted to unfamiliar conditions.

Urban population growth created unprecedented demographic density, transforming social structures and the organization of labor.

Industrial Work and the Changing Urban Landscape

As the market revolution advanced, northern cities expanded around factories, workshops, and commercial centers, creating an environment dominated by wage labor and concentrated industry.

Textile mills, ironworks, and machine shops provided employment for thousands of workers.

New canals and railroads connected cities to regional and national markets, reinforcing their economic importance.

Housing expanded rapidly, though often unevenly, giving rise to both prosperous commercial districts and overcrowded working-class neighborhoods.

Market Revolution: A period of rapid economic transformation marked by expanded markets, technological innovation, and increased connectivity through improved transportation networks.

Urbanization brought new challenges, including sanitation issues, fire hazards, and the need for more structured municipal governance. These pressures prompted cities to develop early public services such as night watches, water systems, and organized street planning.

Interactions Between Migration, Urbanization, and Regional Development

Migration and urban growth reshaped regional identities and helped integrate distant parts of the nation into an interconnected economic system. Northern cities functioned as centers of industry, finance, and trade, while the western frontier expanded agricultural production and supplied raw materials.

Social Consequences of Mobility

High levels of mobility influenced family structure, community ties, and labor systems.

Rural-to-urban migration introduced many Americans to wage labor for the first time.

Frontier families adapted to communal cooperation through barn raisings, shared labor, and local militias.

Increased mobility created more fluid social hierarchies, though disparities of wealth widened in both cities and rural regions.

Population movement during this period reflected broader patterns of ambition, opportunity, and economic change. Whether pursuing farmland along the Ohio River or industrial work in northern cities, Americans shaped new communities that transformed the nation’s social and geographic landscape.

This early-1900s stereograph depicts a densely populated immigrant street filled with peddlers, signage, and multi-story tenements, illustrating the crowded urban neighborhoods that developed from nineteenth-century migration patterns. Although slightly later than the syllabus era, it provides a clear visual representation of the market-oriented, immigrant-dense environments emerging in northern cities. The image reinforces the notes’ discussion of urban density and working-class living conditions. Source.

FAQ

Transportation innovations made long-distance movement faster, cheaper, and more predictable. This encouraged families to resettle west of the Appalachians and supported the movement of goods to and from emerging frontier towns.

In northern cities, improved transport networks allowed factories to ship products widely and receive raw materials efficiently, accelerating urban expansion. These links also strengthened economic ties between western farmers and urban markets.

Migrants were drawn by fertile land suitable for commercial agriculture, access to river transport, and the chance to participate in expanding trade networks.

Communities along these rivers often developed:

Milling and processing businesses

Local retail and artisan services

Storage and shipping facilities for agricultural surplus

These opportunities created diversified local economies that went beyond simple subsistence farming.

Immigrants often settled near others from the same region for cultural familiarity, shared language, and access to mutual aid networks.

Such clusters provided:

Employment information through community ties

Religious and social institutions serving specific cultural needs

Protection from discrimination by creating collective support systems

These neighbourhoods became recognisable parts of urban identity.

Frontier settlements struggled with limited infrastructure and the difficulty of transporting goods before roads and canals connected them to wider markets.

They also faced:

Shortages of skilled labour and manufactured goods

Social isolation and limited public institutions

Vulnerability to environmental hazards and conflict over land

Despite these challenges, communities grew as more settlers arrived and local institutions developed.

Population crowding overwhelmed existing housing and waste-disposal systems, leading to frequent outbreaks of disease.

Cities struggled with:

Contaminated water supplies

Accumulated rubbish in streets and alleys

Limited medical knowledge and poor hospital capacity

These problems pushed some municipalities to begin developing basic public services, though progress remained uneven before mid-century.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one specific way in which migration to the American West between 1800 and 1848 contributed to the development of new communities beyond the Appalachian Mountains.

Mark Scheme (Question 1)

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid factor (e.g., availability of cheap land encouraged settlement).

1 mark for explaining how this factor contributed to community formation (e.g., settlers established farms that grew into towns).

1 mark for providing a specific example or detail (e.g., rapid population growth in Ohio leading to the development of market towns along the river).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which immigration to northern cities between 1800 and 1848 transformed urban life in the United States.

Mark Scheme (Question 2)

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for a clear argument or thesis addressing the extent of transformation.

1–2 marks for describing demographic changes (e.g., increased population density, emergence of ethnic neighbourhoods).

1–2 marks for explaining economic effects (e.g., growth of wage labour, expansion of manufacturing).

1 mark for discussing at least one limitation to the level of transformation (e.g., many cities still lacked infrastructure to manage rapid growth).

Responses should include accurate factual evidence drawn from the period 1800–1848.