AP Syllabus focus:

‘The women’s rights movement was both emboldened and divided by the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution.’

The ratification debates over the 14th and 15th Amendments energised women’s rights activists but also exposed deep divisions within the movement. These constitutional changes reshaped women’s strategies for pursuing political equality.

Women’s Rights in the Reconstruction Context

The aftermath of the Civil War opened new conversations about citizenship, rights, and political participation. As formerly enslaved African Americans gained constitutional protections, many women’s rights advocates argued that the nation should embrace a broader democratic transformation. The women’s rights movement entered Reconstruction believing it was an opportune moment to achieve long-denied political and civil rights, especially suffrage.

However, the wording and implementation of the Reconstruction Amendments created controversy. These amendments expanded rights for African American men but left women of all races without political inclusion. This reality sparked debates about strategy, priority, and the meaning of universal rights.

The 14th Amendment and Gendered Citizenship

The 14th Amendment introduced the first explicit gendered language into the Constitution by referring to “male inhabitants” in its section on voting rights. This phrasing alarmed women’s rights activists, who viewed it as a step backward.

Citizenship and Gender

Although the amendment defined national citizenship broadly, many women argued that citizenship should include political rights.

Suffrage: The right to vote in political elections and a key component of full political citizenship.

Women reformers claimed that if they were citizens under the 14th Amendment, they were entitled to equal protection of the laws, including voting. The amendment’s emphasis on rights and national belonging strengthened their belief that women’s political status required reconsideration.

Divisions Emerge

The amendment’s wording triggered disagreements over strategy within the movement. Some activists insisted that supporting the 14th Amendment was essential to securing African American rights, even if women were excluded. Others argued that accepting the amendment legitimised gender discrimination at the constitutional level. These debates foreshadowed deeper divisions that would intensify with the 15th Amendment.

The 15th Amendment and the Question of Priorities

The 15th Amendment prohibited states from denying voting rights based on race, colour, or previous condition of servitude, but it did not address gender restrictions. This omission became a turning point for the women’s rights movement.

Supporters and Opponents

Two major positions developed among activists:

Supporters of the amendment believed that African American men’s suffrage was an urgent moral necessity after centuries of enslavement and racial oppression.

Opponents of the amendment argued that it entrenched gender inequality by introducing a second constitutional barrier to women’s voting rights.

These conflicting priorities sharpened internal divisions and led to lasting organisational splits.

The Debate Over Universal Suffrage

Many women’s rights advocates framed the 15th Amendment as an incomplete step toward equality. They contended that true democracy required universal suffrage—the enfranchisement of all citizens regardless of race or gender.

This 1866 petition calls for an amendment banning disfranchisement on the basis of sex, demonstrating how women’s rights activists attempted to tie their demands directly to Reconstruction’s constitutional reforms. Although the document contains signatures and formatting beyond the AP focus, these elements help illustrate the scope and organisation of early suffrage advocacy. Source.

The debate over whether to oppose or strategically accept the amendment showcased differing visions of how reform should progress in a nation emerging from civil war.

Fracturing of the Women’s Rights Movement

Growing disagreements over the Reconstruction Amendments led to formal separation within the movement.

National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA)

Founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the NWSA rejected the 15th Amendment because it excluded women. The organisation:

This photograph depicts members of the National Woman Suffrage Association displaying their banner, symbolising the organisation born from disagreements over the 15th Amendment. Although the image dates from the early twentieth century, it reflects the enduring legacy of Reconstruction-era divisions within the suffrage movement. Source.

Prioritised a federal amendment for women’s suffrage.

Criticised male political leaders for limiting democratic expansion.

Took a more confrontational stance in linking women’s rights to broader citizenship debates.

American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA)

Founded by Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, the AWSA supported the 15th Amendment, arguing that African American men needed immediate protection. The organisation:

Worked within existing political structures.

Focused on securing women’s suffrage through state-level campaigns.

Emphasised unity with abolitionist allies.

These contrasting strategies reflected differing interpretations of the movement’s goals and the best path forward.

Legal Challenges and the “New Departure”

Despite internal conflicts, many suffrage activists pursued innovative legal strategies. The New Departure approach claimed that the Constitution already granted women the right to vote as citizens. Women attempted to register, cast ballots, and challenge their exclusion in court.

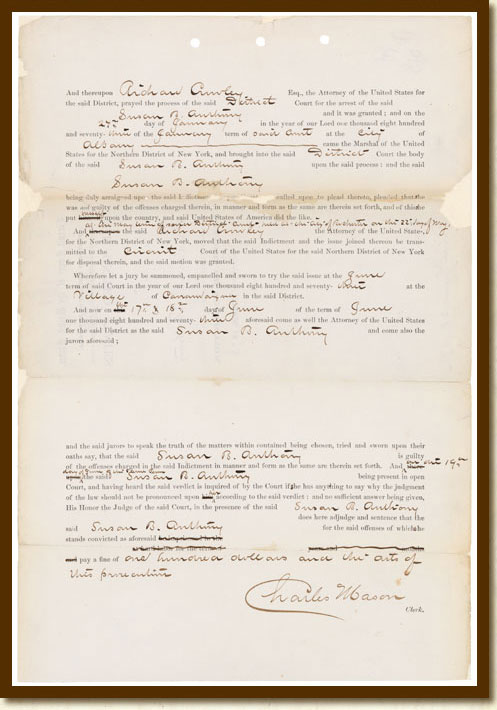

This conviction record from Susan B. Anthony’s 1873 trial demonstrates how suffragists used the New Departure legal strategy to argue that the 14th Amendment already granted women voting rights. The handwritten legal text exceeds syllabus requirements but provides a concrete example of Reconstruction-era constitutional testing. Source.

Although these attempts were unsuccessful, they underscored the belief that constitutional principles of equality should apply to women as well as men.

New Departure: A Reconstruction-era legal argument asserting that women already possessed suffrage rights under the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of citizenship and equal protection.

The Supreme Court’s rejection of this reasoning in Minor v. Happersett (1875) confirmed that suffrage was not an automatic consequence of citizenship, reinforcing the need for a dedicated amendment.

Broader Implications for Women’s Rights

The Reconstruction Amendments shaped both the rhetoric and strategies of the women’s rights movement. They inspired activists by demonstrating that the Constitution could be used to expand rights, yet they also revealed the limits of reform when political coalitions fractured.

Key Effects of the Amendments on the Movement

Emboldening Effect: Women saw constitutional change as a pathway to equality.

Divisive Effect: Disagreement over advocacy strategies caused lasting organisational fractures.

Strategic Shift: Activists increasingly focused on securing a federal amendment specifically for women’s suffrage.

As Reconstruction redefined national citizenship, women’s rights activists grappled with the challenge of inclusion, shaping the trajectory of the suffrage movement into the twentieth century.

FAQ

This marked the first time the Constitution explicitly limited a political category by gender. Activists feared it would strengthen legal justifications for excluding women from voting and holding office.

It suggested that lawmakers were willing to constitutionally enshrine gender distinctions even while expanding rights for other groups. This signalled to many women that without direct action, their political marginalisation would deepen.

Many activists argued that the principles behind the amendments—particularly citizenship and equal protection—should logically apply to women.

Some adopted the New Departure strategy, asserting that women already had constitutional voting rights. Others used petition campaigns, public lectures and test cases to force courts and legislators to confront the inconsistency between democratic rhetoric and gender exclusion.

Abolitionists generally prioritised securing suffrage for African American men, which aligned them with the AWSA’s stance.

Women who valued this alliance tended to support the 15th Amendment despite its exclusion of women. Those who felt betrayed by abolitionist leaders—believing women’s rights were sacrificed—were more likely to join the NWSA.

The 15th Amendment directly addressed voting rights, a central aim of the women’s movement.

Because it enfranchised African American men but not women, activists disagreed over whether to support incremental progress or oppose the amendment on principle. This disagreement sharpened ideological and strategic fractures that became formal organisational splits.

The disputes forced activists to refine their arguments, organisational structures and constitutional strategies.

The split between NWSA and AWSA created two distinct paths: one pursuing federal change and the other working through states. These diverging approaches eventually shaped the campaigns that led to the 19th Amendment, showing how Reconstruction debates had lasting consequences well beyond the 1870s.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the 14th or 15th Amendment affected the strategies or priorities of the women’s rights movement during Reconstruction.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award marks for the following, up to a maximum of 3:

1 mark for identifying a specific impact of the 14th or 15th Amendment on women’s rights activism (e.g., gendered language in the 14th Amendment, exclusion of women from the 15th Amendment).

1 additional mark for explaining how this development shaped the movement’s strategies or priorities (e.g., legal testing through the New Departure, push for a federal suffrage amendment, organisational shifts).

1 additional mark for providing brief contextual insight about why this change mattered within Reconstruction.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how disagreements within the women’s rights movement over the 14th and 15th Amendments reflected broader debates about equality and citizenship in the Reconstruction era.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for the following, up to a maximum of 6:

1–2 marks for describing the major points of disagreement within the women’s rights movement (e.g., NWSA vs. AWSA positions, debates over universal suffrage vs. immediate Black male suffrage).

1–2 marks for explaining how these divisions connected to larger Reconstruction-era debates on citizenship, equality, or constitutional interpretation.

1–2 marks for analysis showing insight into consequences or significance (e.g., long-term organisational splits, shifting advocacy strategies, differing visions of democratic reform).

Responses that are well-structured, historically accurate, and analytical should receive marks at the top of the range.