AP Syllabus focus:

‘Access to natural and mineral resources, economic opportunity, and the search for religious refuge increased migration to and settlement in the West.’

Access to resources, economic possibilities, and the promise of refuge inspired tens of thousands of Americans and migrants to resettle in the West during the mid-19th century.

Motives for Moving West

Access to Natural and Mineral Resources

A major driver of westward migration was the lure of natural and mineral resources, which settlers believed could provide prosperity and long-term security. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 sparked mass migration and intensified the idea that the West contained vast, untapped riches.

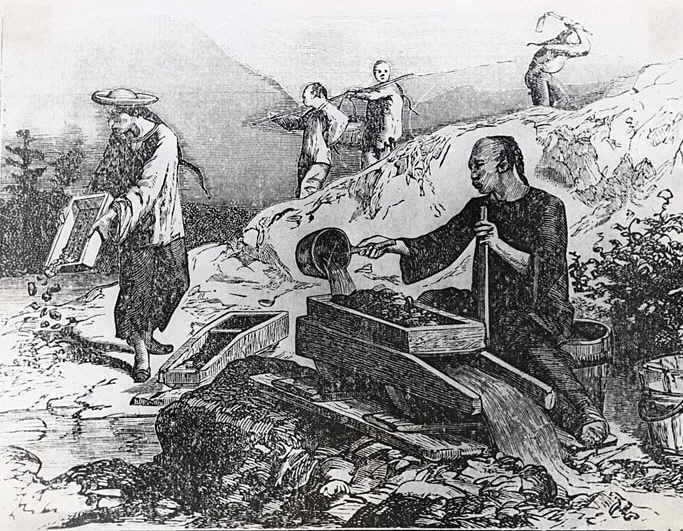

Gold miners work a California claim using simple tools and wooden equipment, seeking wealth during the California Gold Rush. Their labor illustrates how mineral discoveries transformed the West into a magnet for economic opportunity. The presence of Chinese miners reflects broader international migration patterns, a detail that extends slightly beyond the syllabus but supports the context of western mining regions. Source.

Settlers pursued resources such as gold, silver, fertile soil, forests, and grazing land, seeking opportunities unavailable in the crowded East.

Natural resources: Materials such as minerals, timber, water, and fertile land that occur in nature and can be used for economic gain.

The Gold Rush attracted not only Americans from eastern states but also migrants from Latin America, Europe, and Asia. Mining towns quickly formed in California, Colorado, and Nevada, creating new markets and demanding transportation networks. Beyond minerals, migration was also fueled by expanding agricultural possibilities. The rich farmlands of Oregon, California, and the Great Plains encouraged farming families to migrate in groups and form new agricultural communities. These settlers viewed the West as a place where they could acquire land at lower cost and with far greater independence than in the increasingly industrial East.

Economic Opportunity and Social Mobility

The search for economic opportunity became intertwined with the United States’ broader ethos of mobility and self-improvement. Many believed that moving westward would allow them to redefine their economic futures. Land speculation, ranching, mining, and commercial agriculture opened pathways to upward mobility for those willing to endure hardship.

Land in the West offered:

Lower purchase costs than eastern farmland

Potential profit from cultivating previously undeveloped land

Opportunities for livestock raising and cattle operations

Mining regions encouraged investment, labor specialization, and town-building

Expanding markets in California and new western territories stimulated commerce and trade

Speculation: The practice of purchasing land or goods with the expectation of future profit from rising value.

For laborers, artisans, and small farmers, western migration presented a chance to escape stagnant wages or crowded conditions in coastal cities. Even those who did not find mineral wealth often benefited from commercial opportunities created by the influx of settlers. Merchants, blacksmiths, carpenters, and transport providers built thriving communities that served mining and farming populations.

Transportation, Communication, and Government Support

Although the subsubtopic focuses primarily on motives, it is important to recognize how transportation improvements made westward movement more feasible, thereby intensifying these motives. By the 1840s and 1850s, migrants relied on wagon trails such as the Oregon Trail, Santa Fe Trail, and Mormon Trail, which allowed organized and predictable travel into western regions.

This National Park Service map traces the Mormon Pioneer Trail from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Salt Lake Valley. It illustrates how religious communities translated their search for refuge into a defined overland migration corridor. The geographic focus extends slightly beyond the syllabus wording but directly supports the discussion of religiously motivated westward movement. Source.

Government expeditions mapped routes and increased public confidence that migration could be successful.

Key enablers of westward movement included:

Expanded wagon trails and guidebooks

Federal military forts protecting settlers

Increasing availability of steamships and rail links in the East

Growth of commercial networks supplying migrants

Refuge and Community-Building in the West

One of the most powerful motivations for moving westward was the search for religious refuge. During this period, minority religious groups sought isolation from persecution and the opportunity to build communities aligned with their beliefs.

The most notable migration rooted in religious refuge was the movement of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). After facing violent attacks in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois, the Mormons—led by Brigham Young—migrated to the Salt Lake Valley beginning in 1846.

This painting shows Mormon families crossing the frozen Mississippi River as they flee Nauvoo in the mid-1840s. The caravan of wagons and livestock highlights the hardships endured by migrants seeking religious refuge. This dramatic setting emphasizes both the physical danger and determination behind westward religious migration. Source.

They sought autonomy and a safe environment to practice communal living and religious teachings. The West offered geographic isolation, fertile land for irrigation, and the ability to build settlements based on shared values.

Religious refuge: The movement of individuals or groups seeking safety from persecution and the freedom to practice their faith.

Beyond religious motivations, other groups sought cultural or social refuge. Immigrants from Europe, particularly German and Scandinavian families, migrated to the Midwest and Great Plains to establish farming communities resembling those of their homelands. The West allowed these groups to maintain cultural traditions while gaining land and autonomy.

Migration as a Reflection of American Ideology

Motives for westward movement were closely connected to developing American beliefs about the nation’s future. Many Americans associated the West with independence, opportunity, and the possibility of self-determination. Westward migration aligned with broader ideological currents that celebrated mobility, property ownership, and the expansion of republican values.

Settlers believed the West offered:

The possibility of self-made prosperity

Escape from class divisions in older states

A chance to claim land and build communities

Freedom from religious or cultural discrimination

While these ideological beliefs overlapped with Manifest Destiny, the motives for moving west described here focused primarily on material, economic, and social incentives that drew individuals and families across the continent.

Settlement Patterns and Regional Transformation

As settlers arrived, migration reshaped the demographics and economies of western territories. California’s population surged after the Gold Rush, transforming it into a diverse, rapidly developing society. In Oregon and the Great Plains, farming communities expanded American agricultural production. Regions like Utah became centers of religiously organized settlement.

Patterns influenced by motives for migration:

Mining camps evolving into permanent towns

Rapid population booms accelerating statehood bids

Agricultural communities shaping regional economies

Cultural enclaves forming around immigrant groups

These motives, grounded in resources, opportunity, and refuge, played a critical role in the transformation of the American West and the nation’s expansion during the mid-19th century.

FAQ

Many Americans associated the West with the chance to achieve personal autonomy in ways less available in the industrialising East. The prospect of owning land outright, managing one’s own labour, and avoiding wage dependency aligned with a cultural ideal of self-sufficiency.

This belief often encouraged families and young men to endure risky journeys because the West promised a lifestyle shaped by individual choice rather than established social hierarchies.

Guidebooks became widely available in the 1840s and offered practical advice about routes, supplies, climate, and interactions with Indigenous peoples.

They also served as promotional tools, portraying the West as a place of opportunity.

Publishers highlighted fertile soil and abundant resources.

Illustrations and testimonials depicted successful farms and mining ventures.

These texts often exaggerated favourable conditions but nonetheless helped popularise migration.

Single men were more likely to target mining regions where rapid profits seemed possible. They moved fluidly from one strike to another, creating transient communities.

Family groups tended to prioritise agricultural regions, seeking stable environments for long-term settlement. Their migrations were slower, more organised, and more dependent on community networks formed during travel.

Many minority denominations preferred to remain in the East because:

Their communities were locally rooted and reliant on existing economic networks.

Some believed endurance and reform within society were preferable to withdrawal.

Migration was costly, dangerous, and logistically demanding, limiting the feasibility of long-distance relocation.

These factors often outweighed the appeal of remote settlement.

Migrants frequently held idealised visions of western landscapes, expecting mild climates, fertile plains, and abundant water.

Reports from explorers and early settlers emphasised rich soil in Oregon, mild Californian winters, and clear mountain streams in the Rockies. Yet many migrants were unprepared for arid environments, harsh winters, or flooding, demonstrating how promotional narratives sometimes obscured the region’s environmental realities.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why access to natural or mineral resources encouraged migration to the American West in the mid-nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., discovery of gold or availability of fertile land).

1 mark for describing how this resource encouraged movement (e.g., promise of wealth, affordable land for farming).

1 mark for demonstrating historical specificity (e.g., reference to the 1848 California Gold Rush or mineral strikes in the Sierra Nevada).

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which economic opportunity and the search for religious refuge shaped patterns of westward migration between the 1840s and 1850s.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for identifying accurate motivations for migration (economic opportunity such as mining or farming; religious refuge such as the Mormon migration).

1–2 marks for explaining how these motivations shaped observable migration patterns (e.g., mass movement to mining regions; establishment of religious settlements in Utah).

1–2 marks for providing well-selected historical evidence (e.g., California Gold Rush, Mormon Trail, formation of agricultural communities in Oregon or the Great Plains).

Responses reaching 6 marks will show clear analysis of relative significance or extent, supported by precise examples and coherent explanation.