AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the 1840s and 1850s, Americans debated rights and citizenship for different groups living in the United States.’

Americans in the 1840s and 1850s fiercely contested the boundaries of citizenship, rights, and belonging, debating who could participate in the nation’s political community and under what conditions.

Expanding the Nation and Expanding the Debate

Intense national growth during this period magnified disputes over who counted as an American. The annexation of new territories, accelerating immigration, and rising sectional tensions meant that political leaders and ordinary Americans were forced to confront unresolved questions about status, loyalty, and identity. As populations diversified, conflicts emerged over who deserved legal protections, access to institutions, and guarantees of equality under the Constitution.

Citizenship in a Republic Under Pressure

As the United States expanded geographically and demographically, formal citizenship became increasingly contested. Many Americans believed that expanding the republic required clarifying its political membership, especially as new groups entered or were incorporated into the country. Others argued that the rights associated with citizenship should remain restricted to protect national stability and white political dominance.

Competing Views of Citizenship

Political leaders and reformers articulated sharply different visions of inclusion for groups such as African Americans, women, immigrants, and Indigenous peoples. These debates stemmed from broader conflicts over race, labor, religion, and the meaning of republican values.

Legal and Political Frameworks

The Constitution contained no single definition of citizenship, allowing states to develop their own criteria. National debates over citizenship therefore frequently reflected state-level disputes about suffrage, property ownership, racial exclusion, and political representation.

Debates Over African American Rights

Free African Americans—especially in the North—lived in a legal limbo. They were often denied rights such as voting, jury service, and equal protection, even while some states recognized them as citizens. Many white Americans used racial arguments to exclude African Americans from political membership, claiming such restrictions preserved social order.

The Role of Slavery in Citizenship Arguments

Southern politicians insisted that citizenship belonged exclusively to white men and argued that enslaved people were property, not persons with rights. These arguments shaped national politics and influenced federal legislation, contributing to rising sectional conflict.

Rights of Enslaved People and the Fugitive Slave Debate

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 intensified disputes over federal authority and the rights of African Americans.

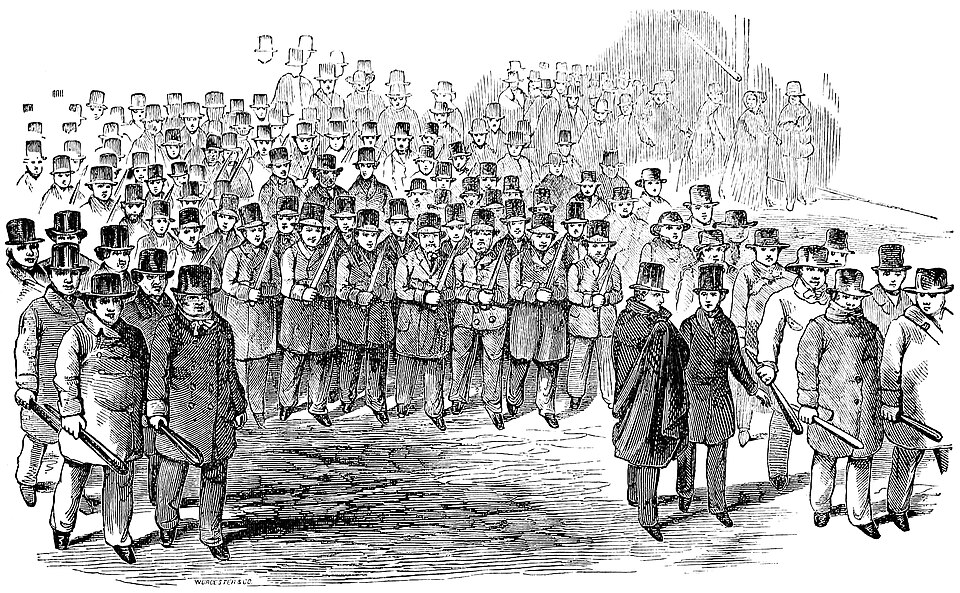

Engraving of Boston police and night watch conveying the fugitive slave Thomas Sims to a vessel that would return him to the South under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The tight formation of armed officers highlights the extent of state and local cooperation in enforcing a pro-slavery federal law, despite abolitionist opposition. The background crowd adds contextual detail beyond the syllabus but illustrates public controversy surrounding fugitive slave rendition. Source.

Its requirement that citizens assist in the capture of runaway enslaved people angered many Northerners and raised fundamental questions about due process and individual liberty. Critics argued that the act denied basic legal protections to African Americans, while supporters claimed it upheld constitutional obligations.

Personal Liberty Laws

Several Northern states passed personal liberty laws to protect free Black residents from kidnapping and to resist federal enforcement. These laws highlighted growing tensions between state sovereignty and federal power and intensified the debate over who the law was meant to protect.

Debates Over Immigrant Rights and Nativism

Large waves of Irish and German immigration provoked public anxieties about cultural change, economic competition, and political loyalty. Many native-born Americans argued that immigrants—even if white—should face restricted rights until they demonstrated cultural assimilation.

The Rise of Nativist Politics

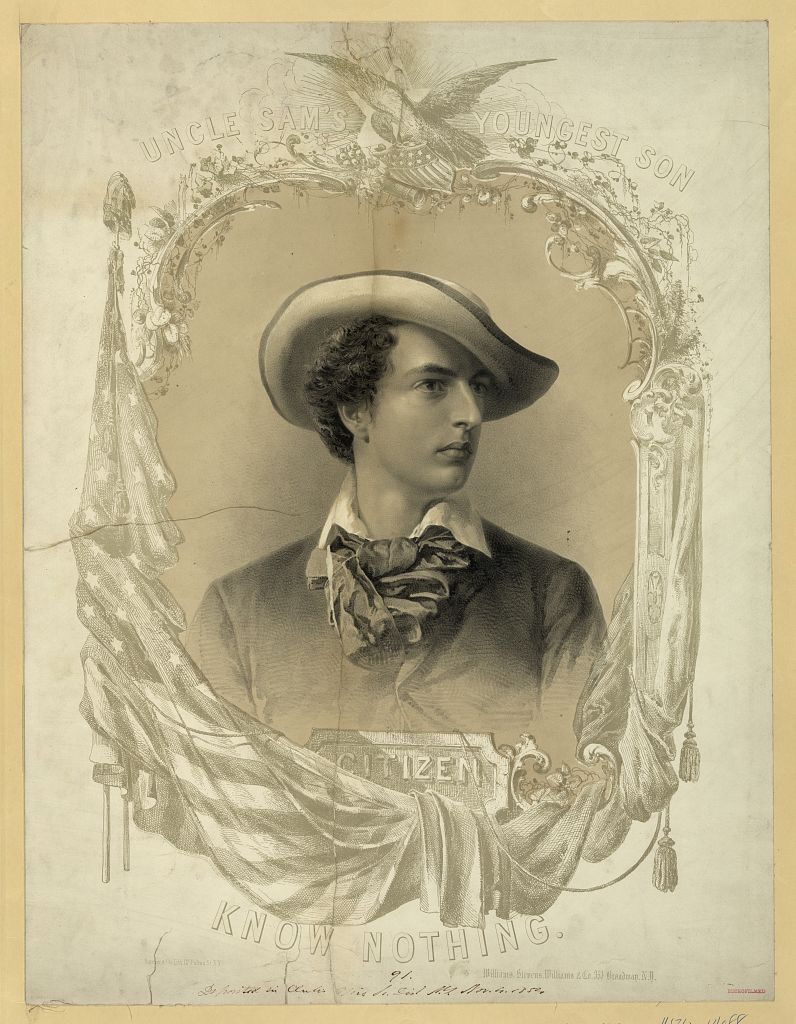

The Know-Nothing Party mobilized around fears that Catholic immigrants threatened American political institutions.

Lithograph titled “Uncle Sam’s youngest son, Citizen Know Nothing,” depicting the Know-Nothing ideal of the native-born Protestant citizen. Decorative patriotic symbols emphasize the party’s belief that immigrant and Catholic influence threatened American political institutions. Some ornate details exceed the syllabus scope but help visualize nativist constructions of citizenship. Source.

They sought policies limiting immigrant voting rights, extending naturalization periods, and protecting what they described as traditional American values. These political efforts represented a broader struggle over whether U.S. citizenship was rooted in birthplace, belief, or cultural identity.

Women and the Question of Citizenship

Women possessed few legal rights under coverture, a legal doctrine that subsumed a married woman’s identity under her husband’s. Although both reformers and women’s rights activists challenged this system, most Americans in the 1840s and 1850s did not believe women should have equal citizenship.

The Early Women’s Rights Movement

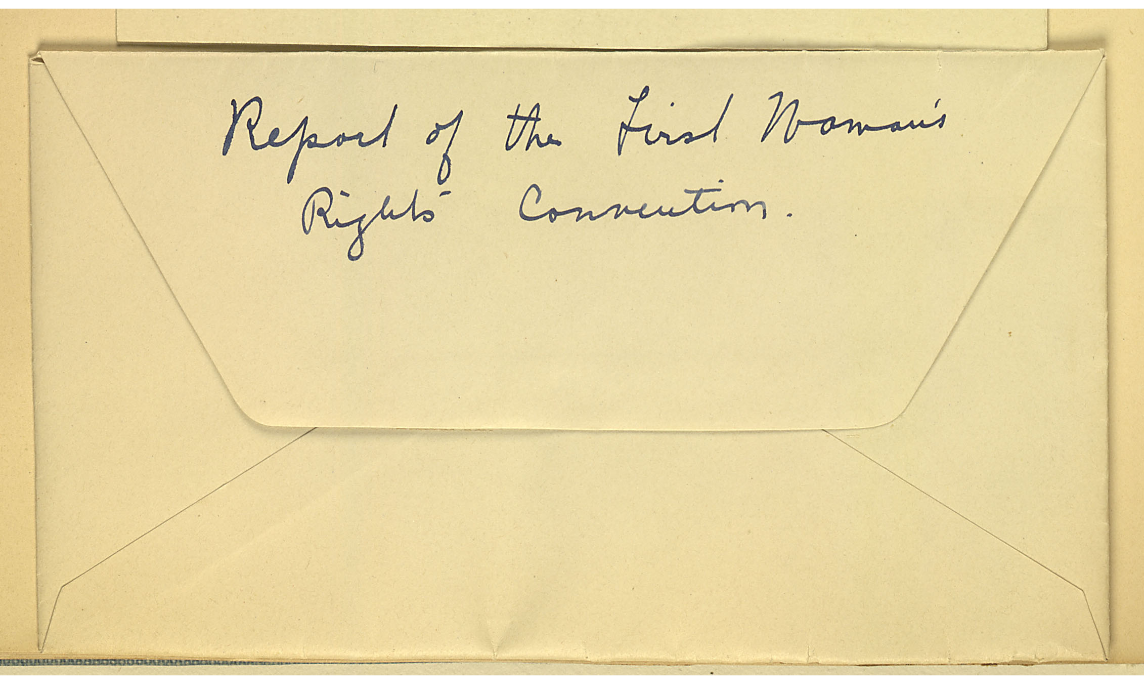

The Seneca Falls Convention (1848) declared women entitled to the same rights as men, including suffrage.

Title page of the Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention, containing the Declaration of Sentiments issued at Seneca Falls. Its formal printed layout shows how women framed their political demands using the same documentary conventions as other civic movements. While visually dense, it effectively emphasizes that women’s rights activists articulated citizenship as a matter of legal equality. Source.

Although their demands gained limited immediate support, the convention underscored the era’s growing contest over political inclusion and set the stage for later national movements.

Indigenous Peoples and Debates Over Sovereignty

Indigenous nations faced continued dispossession, forced migration, and legal marginalization. Most U.S. leaders rejected the idea that Indigenous peoples could become citizens without abandoning their sovereignty and cultural practices. Federal policies privileged land acquisition and expansion over the recognition of Indigenous rights.

Citizenship and Assimilation

Some reformers promoted assimilation as a pathway to limited rights for Indigenous individuals, but this approach demanded cultural erasure. The dominant political view held that Indigenous nations were separate political entities rather than communities eligible for U.S. citizenship.

Citizenship in a Changing National Landscape

By the end of the 1850s, the question of citizenship had become inseparable from national debates about race, rights, and the future of the Union. Divergent regional ideologies, intensified by political crises and demographic shifts, prevented Americans from reaching a shared definition of who belonged within the nation’s civic community. These controversies planted the seeds for the sweeping debates over rights and citizenship that would emerge during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

FAQ

Definitions varied widely across the North. Some states, such as Massachusetts, recognised free African Americans as citizens with limited political rights, including access to courts and limited suffrage.

Other states, including Ohio and Indiana, restricted their movement, denied voting rights, or required registration papers.

These inconsistencies created a patchwork of legal statuses that shaped national debates about who qualified for citizenship.

Religion became a proxy for political loyalty. Many native-born Protestants believed Catholic immigrants owed allegiance to the Pope and would undermine republican institutions.

This assumption fuelled:

• stricter naturalisation proposals

• fears about Catholic schools

• the rise of nativist movements such as the Know-Nothing Party

Although unfounded, these beliefs shaped public discussions about who could be trusted with political rights.

Because the Constitution provided no single definition of citizenship, both states and the federal government claimed authority to decide status.

States determined:

• voting rights

• eligibility for public office

• property and contract rights

The federal government influenced citizenship through immigration laws and enforcement measures such as the Fugitive Slave Act.

Conflicting claims intensified disputes over rights for African Americans, immigrants, and women.

While voting rights were central, activists also linked citizenship to broader civil and legal reforms. Many argued that married women should control their own wages and property, challenging coverture.

They also demanded:

• access to higher education

• expanded employment opportunities

• equal treatment under the law

These arguments positioned women’s rights within national debates about the meaning of political and legal personhood.

Most policymakers viewed Indigenous nations as separate political entities rather than populations eligible for incorporation into the U.S. civic community.

This position stemmed from:

• beliefs that Indigenous sovereignty conflicted with U.S. authority

• assumptions that Indigenous cultures were incompatible with American institutions

• federal priorities focused on land acquisition rather than rights protection

As a result, debates over citizenship rarely included Indigenous perspectives, even as federal policies profoundly disrupted their lives.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which debates over rights and citizenship in the 1840s–1850s reflected wider social or political tensions in the United States.

Mark Scheme (1–3 marks)

1 mark – Identifies a valid example (e.g., fugitive slave laws, nativist responses to immigration, women’s rights challenges, or disputes over free Black citizenship).

1 additional mark – Provides a clear explanation of why this example reveals wider tensions (e.g., sectional conflict, anxieties about demographic change, gender norms).

1 additional mark – Shows specific contextual awareness (e.g., mentioning the Know-Nothing Party, Seneca Falls Convention, or Northern personal liberty laws).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which competing ideas about citizenship shaped political debates in the United States during the 1840s and 1850s.

Mark Scheme (4–6 marks)

4 marks – Describes at least two relevant areas where citizenship debates were significant (e.g., rights of free African Americans, immigration and nativism, women’s rights, Indigenous sovereignty).

5 marks – Shows explanation of how these debates influenced political developments, legislation, or sectional divisions (e.g., Fugitive Slave Act controversy, rise of the Know-Nothing Party, legal resistance in Northern states).

6 marks – Provides a well-developed analysis showing the extent of the impact, making clear links between competing citizenship ideologies and broader national tensions leading toward the Civil War.