AP Syllabus focus:

‘National leaders and the courts tried to resolve slavery in the territories, including through the Compromise of 1850.’

Origins of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 emerged from mounting sectional disputes over how to organise and govern the vast lands acquired through the Mexican Cession.

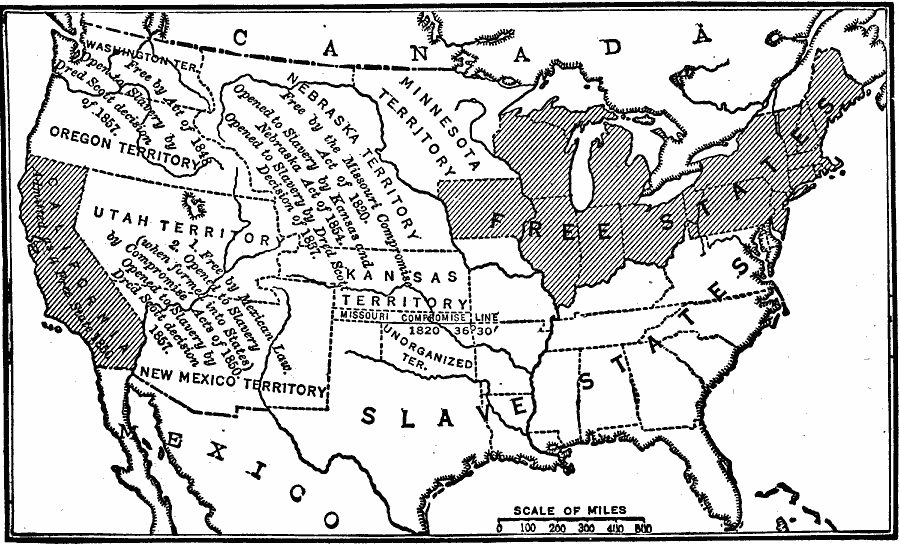

This map illustrates the geographic outcomes of the Compromise of 1850, including California’s admission as a free state and the territorial organisation of Utah and New Mexico. It clarifies how lawmakers attempted to balance sectional interests across the continent. The map also includes additional regional labels and borders not required by the syllabus but helpful for contextual understanding. Source.

As California’s rapid population growth pushed it toward statehood and other territories awaited political organisation, the unresolved question of slavery’s expansion threatened to destabilise the Union. Many Americans hoped that a new national agreement could restore balance between free and slave states and prevent intensifying sectional divisions from spiralling into crisis.

Pressures Created by the Mexican Cession

Conflicts over western territories grew because:

California sought admission as a free state, upsetting the Senate balance.

New Mexico and Utah required territorial governments that needed rules regarding slavery.

Southern leaders feared permanent political marginalisation if new free states outnumbered slave states.

Northern politicians opposed measures that appeared to strengthen or legitimise slavery’s expansion.

These pressures created an urgent need for a national political solution, prompting congressional leaders to craft a sweeping package of bills.

Key Components of the Compromise

The Compromise consisted of several measures designed to appeal to both northern and southern interests. Rather than a single law, it was a collection of bills passed separately, reflecting the complexity of the issues involved.

California and the Issue of Balance

California was admitted to the Union as a free state, immediately altering the delicate numerical balance in the Senate.

Free state: A U.S. state in which slavery was prohibited under state law.

Southern leaders opposed this shift, but they accepted it in exchange for concessions elsewhere in the package.

Territorial Organisation in the West

The Compromise created two new territories—Utah and New Mexico—without specifying whether slavery would be allowed. Instead, the issue would be determined by popular sovereignty, the belief that settlers should vote to decide the status of slavery.

Popular sovereignty: A doctrine asserting that the residents of a territory should decide whether to permit or prohibit slavery.

This approach was intended to reduce sectional conflict by delegating contentious decisions to local settlers rather than Congress.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

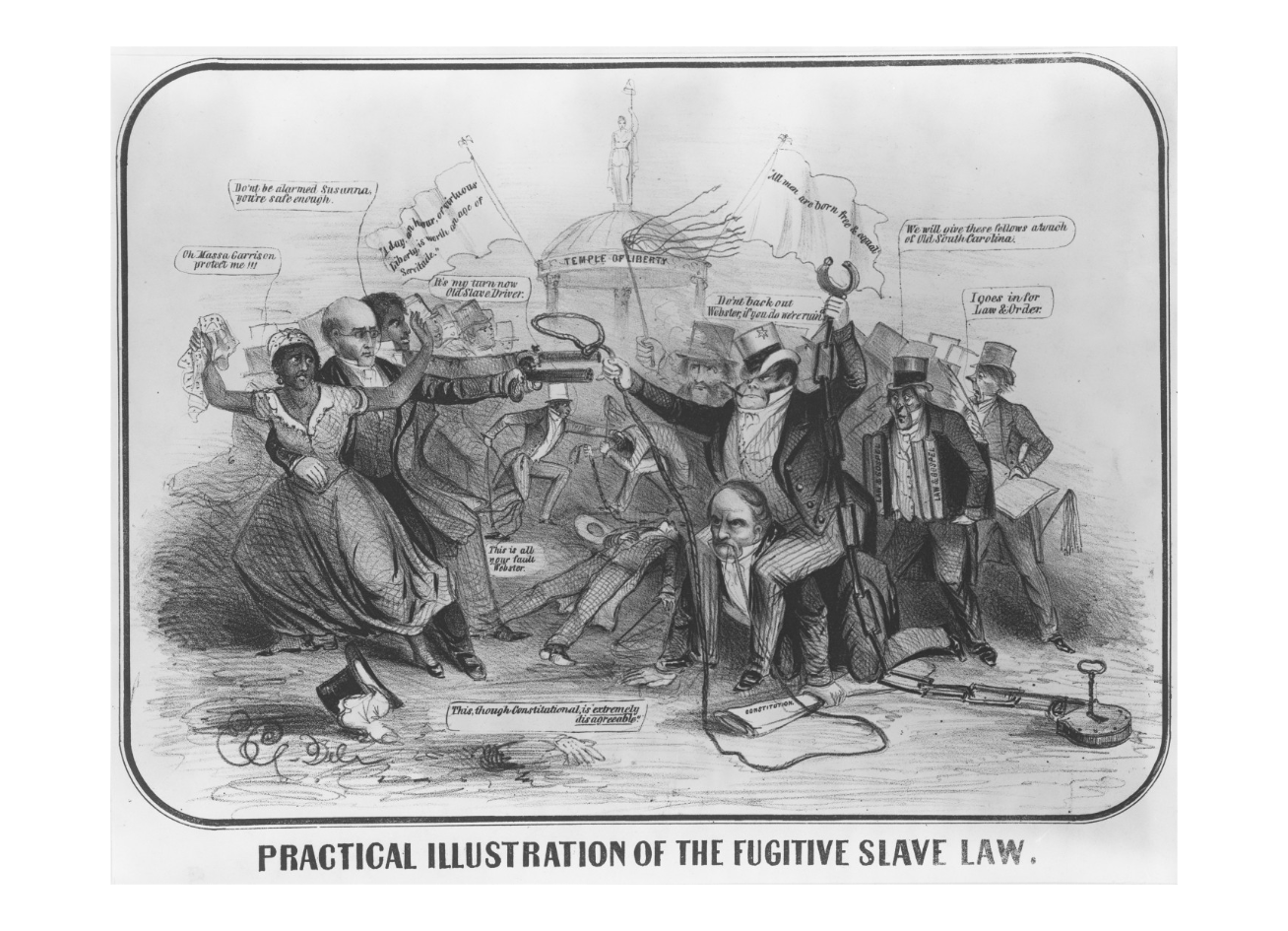

One of the most controversial components was the strengthened Fugitive Slave Act, which mandated federal support in capturing and returning enslaved people who had escaped to free states.

This cartoon criticises the Fugitive Slave Act by depicting abolitionists clashing with enforcers of the law, symbolised by Daniel Webster aiding a slave catcher. It conveys the widespread Northern belief that the act represented an intrusive federal mandate supporting slavery. Though highly symbolic, the imagery reinforces the controversy sparked by the strengthened law. Source.

Key provisions included:

Federal commissioners, rather than juries, adjudicating fugitive cases.

Severe penalties for individuals assisting escape attempts.

Legal obligations placed on citizens in free states to cooperate with enforcement.

Northern resistance intensified because many viewed the law as a federal intrusion into states’ rights and an expansion of slaveholder power.

Abolition of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.

The compromise banned the slave trade—though not slavery itself—in the nation’s capital. This measure symbolically aligned the capital with anti-slavery sentiment while protecting Southern interests by allowing slavery to continue in the district.

Motivations of National Leaders

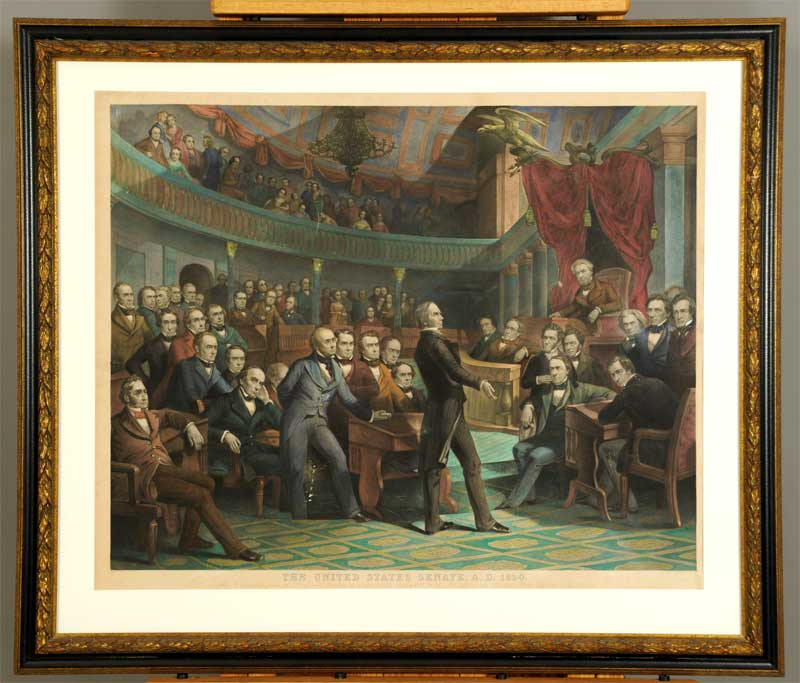

Prominent figures such as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Stephen Douglas believed that compromise was essential to preserving national unity.

This engraving shows Henry Clay speaking before the United States Senate as Webster and Calhoun look on, capturing the pivotal debates surrounding the Compromise of 1850. It reflects how national leaders attempted to manage sectional tensions through rhetoric and political negotiation. Additional background details of the Senate chamber extend beyond syllabus requirements but enhance historical context. Source.

Clay championed a broad package designed to offer something to each section, while Douglas later broke the plan into separate bills to ensure passage.

Their work reflected a larger belief that national leadership could manage sectional conflict through negotiation, political balance, and legal mechanisms. Courts also played a role, particularly in interpreting fugitive slave provisions and defining federal authority.

Responses Across the Nation

Reactions to the Compromise varied widely, reflecting the nation’s deep ideological and regional divides.

Northern Reactions

Many northerners supported aspects of the Compromise but denounced the Fugitive Slave Act. Resistance took several forms:

Legal “personal liberty laws” protecting accused fugitives.

Activist networks opposing federal enforcement.

Public criticism of federal overreach into free states.

These responses revealed the growing moral and political opposition to slavery’s influence in national policy.

Southern Reactions

While some southern leaders accepted the Compromise as a necessary concession, others doubted that popular sovereignty would adequately protect slavery’s expansion. Persistent fears of being politically outnumbered made many southerners sceptical about long-term coexistence with an increasingly free-soil North.

The Compromise’s Attempt to Preserve National Unity

The Compromise of 1850 represented a national effort to stabilise the political landscape by dispersing concessions across regions. Leaders hoped that by addressing immediate disputes over territorial slavery, they could extend the Union’s lifespan and postpone sectional rupture.

Short-Term Impact

The Compromise eased immediate tensions by:

Allowing California’s admission.

Providing a process for organising western territories.

Offering policy concessions to both North and South.

Yet its reliance on ambiguous principles, particularly popular sovereignty, left major questions about slavery unresolved.

The Compromise of 1850 thus stands as a significant national attempt to manage sectional conflict, revealing both the creativity and limitations of mid-nineteenth-century political leadership.

FAQ

California’s population boom allowed it to apply for immediate statehood rather than pass through a long territorial phase, forcing Congress to confront the slavery issue quickly.

Its admission as a free state upset the previous balance between free and slave states in the Senate, heightening Southern fears of losing political influence.

This imbalance pushed Southern leaders to demand strong concessions elsewhere in the Compromise.

In theory, popular sovereignty empowered local settlers to decide the status of slavery, reducing tensions by keeping Congress neutral.

In practice, it exposed territories to organised political pressure, migration intended to influence votes, and uncertainty over when and how the decision should be made.

This ambiguity later contributed to violent conflict in other territories, raising doubts about whether the approach could ever function as intended.

Southern leaders believed that demographic and political trends were turning decisively in favour of free states, threatening long-term Southern power.

They worried that limiting slavery’s expansion would eventually weaken the institution economically and politically.

Some also feared that future northern-led governments might take more aggressive steps to restrict or abolish slavery altogether.

The law required ordinary citizens in free states to assist in slave recapture, effectively compelling participation in the enforcement of slavery regardless of personal beliefs.

It denied accused fugitives the right to a jury trial and strengthened federal commissioners’ authority, raising concerns about due process and states’ rights.

These factors made the act a focal point of northern resistance and protest.

The mixed reception to the Compromise showed that piecemeal legislative solutions could delay but not resolve deeper ideological divisions.

Its reliance on popular sovereignty encouraged future lawmakers to use the same approach, setting the stage for later crises such as the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

The Compromise also accelerated the decline of national party unity, as sectional loyalties increasingly overshadowed traditional political coalitions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and explain one way in which the Compromise of 1850 attempted to reduce sectional tension over slavery in the western territories.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid component of the Compromise (e.g., popular sovereignty in Utah and New Mexico, California admitted as a free state, strengthened Fugitive Slave Act).

1 mark for explaining how that measure was intended to address sectional conflict.

1 mark for linking the measure to the broader goal of maintaining national balance or stability.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the Compromise of 1850 reflected competing regional interests in the United States and assess its effectiveness in addressing disputes over slavery in the territories.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least two regional interests (e.g., Northern opposition to slavery expansion, Southern demands for protection of slaveholder rights).

1 mark for describing how specific provisions of the Compromise attempted to satisfy these interests.

1 mark for indicating ways in which the Compromise pleased or displeased each section.

1 mark for evaluating the short-term or long-term effectiveness of the Compromise in reducing conflict.

Up to 2 additional marks for a well-developed, coherent analysis that clearly links the Compromise to shifting political dynamics and escalating sectional tensions.